The Trauma Assessment Unit: The COVID-19 experience from University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire

By Sarah Henning, Matthew Weston, Darryl Ramoutar and The Coventry Trauma and Orthopaedics Team*University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire, Coventry, West Midlands, CV2 2DX, United Kingdom

Corresponding author email: [email protected]

Published 30 June 2020

Abstract

With the rapid spread of COVID-19 around the globe, there was initial concern that NHS emergency services could become overwhelmed. In preparation for this, and to ease pressure on the Emergency Department, trauma attendances to University Hospital, Coventry were redirected to a specialist Trauma Assessment Unit. The unit is staffed by an on-call Orthopaedic registrar with support from other junior doctors, specialist trauma nurses and orthopaedic physiotherapists, under the supervision of an on-call Orthopaedic consultant. This service evaluation assesses the first 102 attendances to our Trauma Assessment Unit and considers the benefits of employing such a system in the COVID-19 crisis and beyond.

Introduction

Worldwide, the COVID-19 virus has resulted in the disruption of normal services offered in both primary and secondary care. In May 2020, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire published our approach to providing specialist Trauma & Orthopaedic care during the pandemic1. This paper describes the creation of a rapid Trauma Assessment Unit (TAU) within the orthopaedic ward as a vital element of our COVID-19 strategy. Our TAU consists of two 6-bed bays, one male and one female, within an orthopaedic ward. Nursing care is provided by two specialised trauma nurses; trained in venepuncture, cannulation and other routine practical skills. The referral protocol for TAU involves the efficient triage of patients in the Emergency Department (ED), relevant diagnostic imaging and fast-track transfer directly to the unit for formal orthopaedic assessment. These patients do not require discussion with the orthopaedic registrar or review of imaging prior to transfer. This protocol was implemented to reduce the burden on ED staff and minimise the time orthopaedic patients spent in ED, given that the majority of ED majors has been converted to a ‘respiratory zone’ for patients attending with typical COVID-19 symptoms. Ambulatory trauma was sent to our elective operating site, so the TAU was only for non-ambulatory trauma or patients who accidentally presented to the wrong hospital site. The aims of this service evaluation were to review the first five weeks of admissions to TAU, to assess the referral protocol and to identify improvements, for both the current crisis and beyond.

Methods

All patients attending TAU from its inception, on 25th March 2020, until 02nd May 2020 were identified using a prospective paper logbook of admissions. Further information was collected from paper records, electronic clinical records and digital imaging. The information collected included demographics, date of attendance, imaging sent from triage, further imaging taken, outcome (discharged, referred to medical team), procedures performed on TAU and COVID-19 status. Patients admitted to the department via other referral routes (such as polytrauma patients or already clerked referrals from ED) were not included in this paper.

Results

In total, 102 patients were identified (40 male, 63 female). The mean age was 72 years (Range 22-101 years). On average, 2.6 patients were seen daily on TAU (mode= 3, range 0-6 patients). See Table 1.

|

|

Weekdays |

Weekends/Bank Holidays |

Overall |

|

Mean admissions |

2.7 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

|

Modal admissions |

3 |

0 |

3 |

Five patients (5%) were admitted to TAU for review by a non-Orthopaedic specialty. This included one patient for Cardiothoracic surgery (who had moved their patients to one of the adjacent areas due to their critical care unit being taken over during COVID-19 pandemic), two patients seen by plastic surgery (for wound complications normally seen in a specialist dressings clinic) and two patients under the medical team (it is unclear why these were seen on TAU but many medical outliers were transferred to our ward areas during the crisis). The remaining 97 patients seen on TAU within our data capture period were referred to Trauma & Orthopaedics.

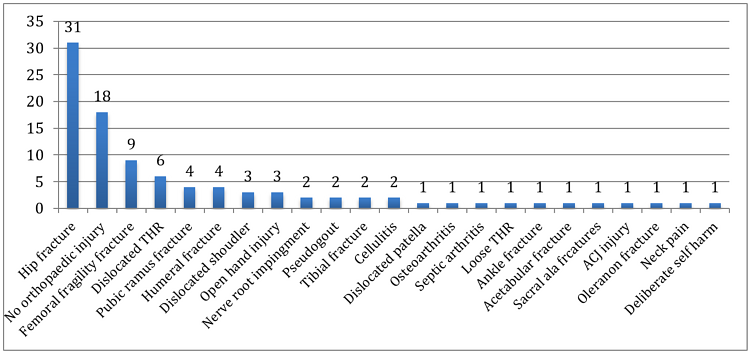

Figure 1: Diagnoses seen on TAU

As seen in Figure 1, the most common reason for presentation to TAU was femoral fragility fracture (number = 40, 31 neck of femur, nine non-neck fracture femur) or no underlying orthopaedic injury requiring admission (number= 18). The 18 patients with no diagnosis made were all elderly with a history of fall and hip pain but no fractures were identified.

Ten patients (10%) seen on TAU required additional imaging to that performed in ED. Three patients required a CT pelvis to exclude hip fracture (one neck of femur fracture identified). In three patients the body part imaged in the initial ED radiographs did not correlate with the clinical history or examination. Two patients, with femoral shaft fractures, required further imaging of the distal femur for pre-operative planning. One patient, with a pathological hip fracture, required full-length femoral films to exclude a distal lesion. One patient was found to have sustained multiple injuries and so a trauma CT was requested.

Of the patients seen on TAU, 28 (28%) were discharged back to their usual place of residence on the day of admission. Seven patients (7%) were referred to the Medical team for further management of non-surgical conditions (fast atrial fibrillation, cellulitis, urinary tract infection, falls investigation and pubic ramus fractures).

Ten patients (10%) were seen with dislocated joints (six total hip replacements, three shoulders and one patella). All of the dislocated hips were reduced in theatre (one reduction was attempted on TAU, without success). All glenohumeral and patella dislocations were reduced under Entonox on TAU.

COVID-19 screening was performed on all patients admitted to TAU, with 11 patients (11%) subsequently testing positive for the virus (one further patient tested negative but subsequently died, with likely COVID-19 registered as the cause of death). All of the patients who tested positive were admitted to TAU between 27th March 2020 and 2nd April 2020, including one patient discharged but who later tested positive in the community. Only one of these patients had symptoms of COVID-19 at presentation to TAU. This patient was seen on 1st April 2020, after deliberate self-harm and a suicide attempt. Their forearm was sutured on TAU, before transfer to the medical team due to pyrexia and fast atrial fibrillation. The patient subsequently tested positive for COVID-19. Two other patients, who attended TAU on the same day as this patient, later developed COVID-19. Of the six patients attending TAU the following day, four developed COVID-19. It is unclear if there is an actual link between these cases, or if they simply represent the peak of the local COVID-19 pandemic. A side room has since been provided for any patients who display symptoms on arrival to TAU.

Three patients (3%) from our cohort have since died: A 99-year-old male with an acetabular fracture, a 93-year-old male with an intra-capsular hip fracture and an 83-year-old male with proximal humeral and olecranon fractures (this patient had 'likely COVID-19' registered as their cause of death). Further deaths may have occurred since the data was collected, but in the interest of rapid results reporting, we did not collect 30-day mortality.

Discussion

Irrespective of the current Coronavirus pandemic, attendances to the Emergency Department have risen exponentially in recent years2. This increased demand puts ever more pressure on the limited resources in ED and leads to delays in obtaining investigations and commencing initial treatment. In addition, the infrastructure in many Emergency Departments is inadequate for dealing with such patient numbers, leading to unsatisfactory scenarios where patients are expected to wait in corridors and where there are insufficient clinical areas to facilitate assessment and treatment of patients with the privacy and confidentiality that they, quite reasonably, expect3. Such occurrences are to the inevitable detriment of the patient’s experience and may also have an adverse effect on clinical outcome4,5. The Coventry TAU was established to ease the burden of trauma care on the Emergency Department during the COVID-19 crisis, given that a large proportion of ED has been converted to a ‘respiratory zone’ to treat suspected COVID-19 cases. In this regard, it has proved effective and is an efficient means of providing initial treatment for orthopaedic trauma. It has reduced the burden of trauma on ED and has allowed patients to wait and be assessed in an appropriate setting with adequate resources at hand. No data was collected on time from presentation to orthopaedic assessment but we suspect that this delay has been reduced. This will be an area for further evaluation once the volume of trauma returns to normal and meaningful data can be obtained for comparison with the traditional referral pathway. In addition, the initial assessment by a specialist, rather than ED, has enabled earlier instigation of appropriate specialist investigations and a definitive treatment plan. This includes early administration of specialist pain relieving measures, such as Fascia Iliaca blocks for hip fractures and skin traction for long bone injuries. Furthermore, our analysis demonstrates that 28% of TAU admissions are suitable for discharge the same day. Whilst this number may appear to represent unnecessary admissions to the unit, early intervention with specialist orthopaedic physiotherapists in this group, undoubtedly improves their prospect of discharge and, thus, relieves pressure on inpatient beds. Furthermore, this specialist physiotherapy input is likely to reduce readmissions and re-attendance. Many patients were also given advice that they normally would have received at a subsequent fracture clinic appointment or offered a telephone follow up, thus allowing fewer face-to-face consultations in the outpatient department.

The model of early, specialist input is well established in other specialties, with Medical Assessment Units (MAU) and Surgical Assessment Units (SAU) common throughout NHS hospitals. In the medical setting, it has been shown to improve the overall patient experience6,7. Whilst acute assessment units are not yet commonplace in Trauma & Orthopaedics, a similar approach has been advocated by Gupta et al. to treat hip fracture patients8. Their paper describes how an Acute Hip Unit (AHU) can improve access to both orthopaedic and orthogeriatric specialist input. This was demonstrated to reduce time from admission to theatre and overall length of stay. Further analysis is required to establish whether TAU can result in similar benefits to other types of trauma and, thus, to determine to future role of such a unit. At the very least, there appears to be a compelling argument for maintaining a TAU beyond the COVID-19 crisis as a means of fast-tracking hip fracture admissions and relieving ED staff of this workload.

Challenges encountered on TAU

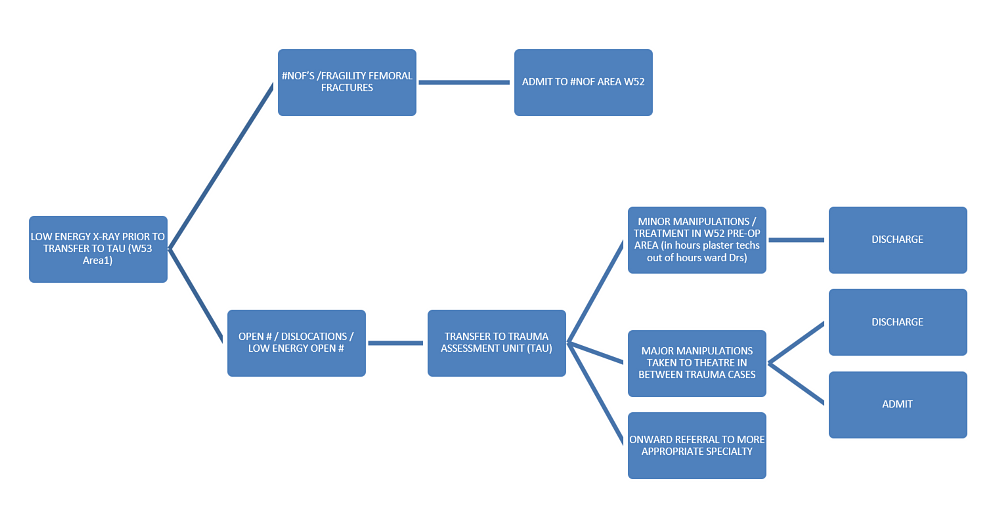

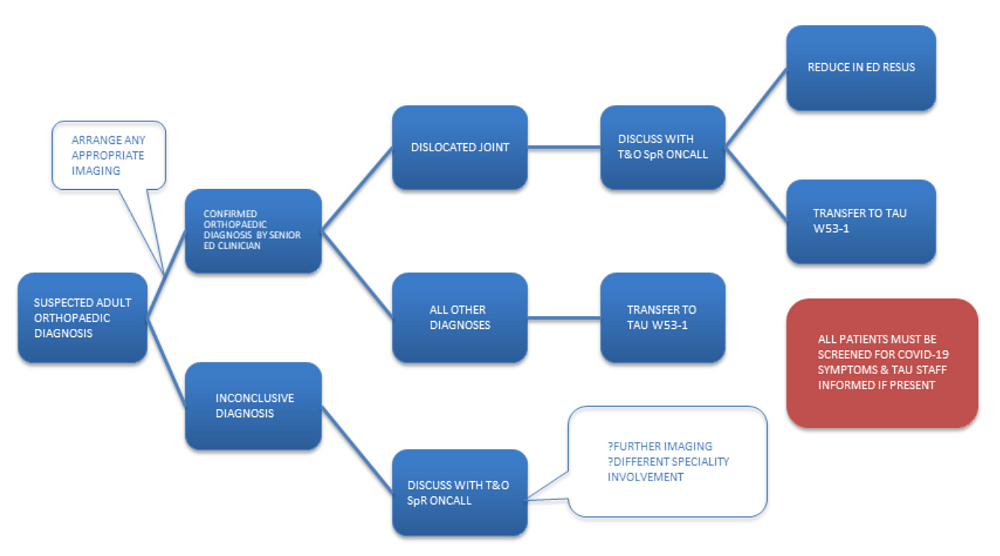

The Coventry TAU was established quickly as a necessity brought about by the COVID-19 crisis. As such, the referral criteria agreed between ED and Orthopaedics prior to its inception were non-specific and allowed maximal diversion of patients away from ED, (see Figure 2). This may go some way to explaining the number of TAU admissions with no identifiable pathology. We would, therefore, urge other units to establish clear and specific referral criteria when setting up a TAU and we hope that our experience in Coventry can serve as guide in doing so. We are currently in the process of refining our criteria based on this review, to ensure that our unit is not overwhelmed when the volume of trauma attendances inevitably rises in the near future, (see Figure 3). One simple factor that may address the majority of unnecessary referrals would be a review of imaging by a senior clinician in ED, or discussion with the orthopaedic registrar, prior to patient transfer from ED. This additional step would also permit further imaging to be obtained prior to transfer, utilising the priority access to radiology services within ED. As such, we plan to include this change in our proposed TAU referral pathway.

Figure 2: Current referral protocol for TAU

Figure 3: Proposed modified referral protocol for TAU

In the early stages of the COVID-19 crisis, all joint dislocations were fast-tracked to TAU prior to reduction. Due to the volume of COVID-19 admissions and the potential risk of aerosol generating procedures with sedation, this service could not initially be provided in ED. As such, many manipulations were performed in the trauma theatre. This, however, is clearly an inefficient use of the trauma list and often results in a delay to achieving reduction of the dislocation. To address this issue, we have arranged for Methoxyflurane (Penthrox®, Galen) to be available for manipulations on TAU. This is a patient-administered inhalational agent, providing the pain relief required for fracture and joint manipulations. It has been shown to be more effective than Entonox or intranasal Fentanyl9,10. Although this drug has not yet commenced use in our unit, we are hopeful that this may provide a long-term solution to the difficulties of arranging sedation in a busy Emergency Department. Nonetheless, certain manipulations are clearly more appropriate for the ED resuscitation room than TAU. There should remain provision for such cases in ED and TAU referral criteria should identify these patients prior to transfer.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis has thrown the entire globe into chaos, with healthcare systems worldwide being stretched in ways not seen in peacetime. As Trauma and Orthopaedic surgeons, we have faced challenges in how to continue the provision of trauma support within the secondary care systems in each of our countries. Here in Coventry, we believe that in setting up the TAU, we have helped both our colleagues and our patients. We hope that through sharing our experience, we may inspire others to consider how they can pursue excellence in trauma care through these unprecedented times and beyond.

References

- Mackay N, Shivji F, Langley C, David M, Syed F, Chapman A, et al. The Provision of Trauma and Orthopaedic Care During COVID-19: The Coventry Approach. The Transient, May 2020. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/the-provision-of-trauma-and-orthopaedic-care-during-covid-19-the-coventry-approach.html.

- Higginson I. Emergency department crowding. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(6):437-43.

- Hanson J, Walthall K. Effects of hallway/corridor and companions on clinical encounters: a possible explanation. Emerg Med J. 2018;35(7):404-5.

- Rasouli HR, Esfahani AA, Nobakht M, Eskandari M, Mahmoodi S, Goodarzi H, Farajzadeh MA. Outcomes of Crowding in Emergency Departments; a Systematic Review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019;7(1):e52.

- Carter EJ, Pouch SM, Larson EL. The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(2):106-15.

- Scott I, Vaughan L, Bell D. Effectiveness of acute medical units in hospitals: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(6):397-407.

- Tripp DG. Did an acute medical assessment unit improve the initial assessment and treatment of community acquired pneumonia--a retrospective audit. N Z Med J. 2012;125(1354):60-7.

- Gupta A. The effectiveness of geriatrician-led comprehensive hip fracture collaborative care in a new acute hip unit based in a general hospital setting in the UK. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2014;44(1):20-6.

- Tomlin PJ, Jones BC, Edwards R, Robin PE. Subjective and objective sensory responses to inhalation of nitrous oxide and methoxyflurane. Br J Anaesth. 1973;45(7):719-25.

- Johnston S, Wilkes GJ, Thompson JA, Ziman M, Brightwell R. Inhaled methoxyflurane and intranasal fentanyl for prehospital management of visceral pain in an Australian ambulance service. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(1):57-63.

*The Coventry Trauma and Orthopaedics Team:

T&O Consultants: Mr Nathanael Ahern, Mr Mateen Arastu, Mr Gevdeep Bhabra, Mrs Anna Chapman, Mr Stephen Cooke, Mr Wael Dandachli, Mr Michael David, Mr Vivek Dhukaram, Mr Stephen Drew, Mr Pedro Foguet, Mr Andrew Fowler, Professor Damian Griffin, Mrs Helen Hedley, Mr Chris Hill, Mr Matthew Jones, Professor Richard King, Mr Jakub Kozdryk, Ms Clare Langley, Mr Thomas Lawrence, Mr Andrew Mahon, Mr John McArthur, Mr Andrew Metcalfe, Mr Chetan Modi, Mr Sunit Patil, Mr Giles Pattison, Mr Housam Raslan, Mr Bryan Riemer, Mr Feisal Shah, Mr Robert Sneath, Mr Tim Spalding, Mr Farhan Syed, Mr Mark Taylor, Mr Peter Thompson, Mr Peter Wall, Miss Jayne Ward, Mr Daniel Westacott, Mr Richard Westerman, Mr Jonathan Young.

T&O Associate Specialist: Mr Asgar Ali

T&O Staff grades: Mr Khalil El-Bayouk, Mr Okpako Ikogho, Mr Ali Saad.

T&O registrars/fellows: Mr Imran Ahmed, Mr Firas Arnaout, Mr Tim Barlow, Mr Tom Cloake, Mr Vito Coco, Mr Christopher Downham, Mr Miguel Fernandez, Mr Kanai Garala, Mr Andrew Grazette, Miss Elizabeth Hedge, Mr James Li, Miss Nicola Mackay, Mr Avi Marks, Mr James Masters, Mr James Miller, Mr Vlad Paraoan, Miss Olivia Payton, Mr Deepak Samson, Mr Alexander Schade, Mr Shafiq Shahban, Mr Faiz Shivji, Mr Christopher Wilding.

Advanced nurse practitioners: Mrs Anna Baker, Mrs Lauren Bellanti, Miss Lucy Dalton, Mrs Filo Eales, Mrs Louise Fraser, Mrs Morag Green, Mrs Gail McCloskey, Mrs Suzanne Woodridge.

Hand co-ordinator: Mr Simon Dickens.

T&O management: Mr Alistair Nutting, Mrs Juliet Starkey, Mrs Elaine Taylor.

Senior nursing management: Mrs Sarah Hartley, Mrs Paula Seery, Mrs Chris Seddon.