The psychology of surgeon-patient relationship revisited

By Kai Nie

| Winner of 2024 Robert Jones Gold Medal and Association Prize |

Introduction

There are well established interactions between psychological factors and physical health1,2. These interactions are complex, reciprocal, and yet to be fully understood. There is compelling evidence linking mental health to clinical outcomes after surgery, particularly joint replacement surgery3,4. Depression increases the risks of dissatisfaction and complications after joint replacement3, and is associated with increased healthcare cost5. Equally a successful joint replacement, with subsequent improvement in pain and function for the patient, can significantly improve mental health6. A number of randomised controlled trials7-9 provided good evidence that some orthopaedic operations have little to no additional benefit over sham surgery. They highlighted the significance of the placebo effect in relation to surgery. The psychology of patients undergoing surgery10 has been explored before, however the psychology of the surgeon-patient relationship is less studied. Meta-analysis in the field of psychotherapy11 suggests the single most influential factor on clinical outcome is the ability of the therapist to form a therapeutic relationship with the patient. In other words, having the 'right' therapist is far more important than having the 'right' psychotherapy. Is there a parallel to the surgeon-patient relationship?

Historical Context

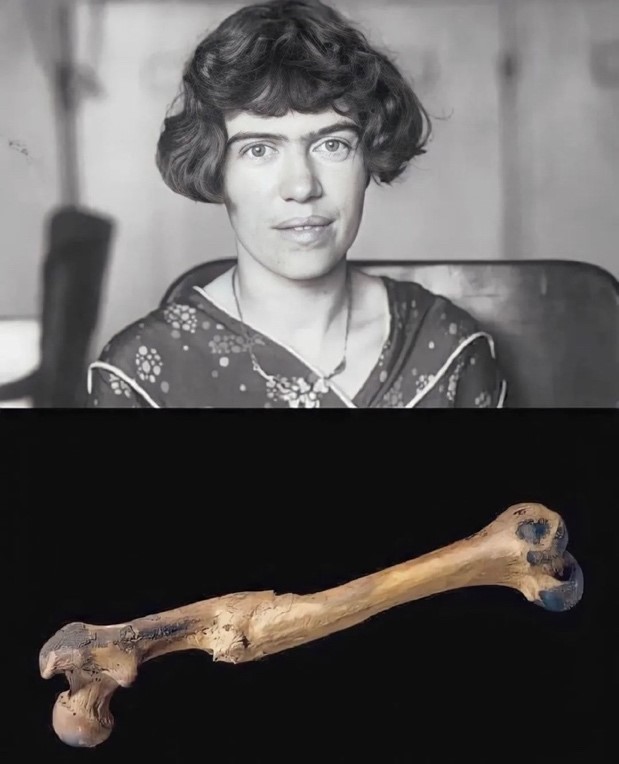

Figure 1: Margaret Mead (1901-1978) and a photograph of a healed femur – unclear whether this is the said femur in her quote, but it nonetheless demonstrates bony union by callus formation through the non-operative management of a mid-shaft femoral fracture.

A 15,000-year-old healed femur (Figure 1) is said to be the first evidence of civilisation, a quote often attributed to the American cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead. The story goes that an animal with a long bone fracture is unlikely to survive in the wild, either succumbing to the injury, or falling prey to its predators. But a healed femur fracture implies that a person must have received care, help and protection. Mead would conclude “helping someone else through difficulty is where civilisation starts”.

Therefore, in some ways the pre-historic predecessors to our specialty heralded the intellectual awaking of Homo Sapiens as a species. Whilst in the intervening millennia, our understanding of physiology and anatomy has exponentially expanded, our natural curiosity has taken us from inside of a cell to the edge of the universe, our appetite for innovation has invented technology that enabled us to attempt incredible feats, surgical or otherwise; one would argue however, that the fundamental values – care, compassion, kindness - that underlines the surgeon-patient relationship remained constant. I would like to imagine in a hundred years from now, in a world where medical knowledge is stored in the Cloud, clinical decisions are taken by Artificial Intelligence (AI), and operations are undertaken by surgical robots; the human touch, the intangible yet very real thing that makes us special, will endure and remain the cornerstone for future generations of surgeons.

Trust

Trust underpins the surgeon-patient relationship and indeed all human relationships. The General Medical Council (GMC) is explicit that doctors “must make care of your patient your first priority” and places a duty on us to be “honest and open, act with integrity, never discriminate against patient or colleagues, never abuse trust in you and public in the profession”12.

Trust is a deceptively complex construct. It is a shared belief that incorporates respect, vulnerability, and control. It often requires individuals to participate in a dynamic, involving suppression of anxiety on one hand (patient), and assumption of responsibility on the other (surgeon). Trust is necessary for even the most basic collaboration between human beings, even more so when the stakes are literally life and limb, as often are the case in surgery. It requires the patient to cede control to his or her surgeon, with the expectation that the surgeon will act with expertise (competence) and in their best interests (beneficence). Trust is to be earned; and one can reasonably argue that, to maintain and justify a patient’s trust in the surgeon and the public’s trust in the profession, is the principal ethical obligation of the surgeon. Openness, honesty, and integrity are key12.

The patient is necessarily in a position of vulnerability. This vulnerability can manifest itself in anxiety, uncertainty, and anger; but also love, gratitude, and idolisation. Therefore, a patient has to rationalise or otherwise reassure themselves to cope. Coping skills are highly variable across the entire population, and many patients might deploy ineffective forms of coping when facing surgery. Examples are avoidance (“I’ll think about the surgery later”), denial (“I’m sure I don’t really need the operation”), or projection (“well, I could tell that surgeon was not sure about the operation and didn’t really want to operate on me”). These are subconscious defence mechanisms the human mind may deploy to protect the Ego13 against stress, theorised originally by Sigmund Freud, and later explored and expanded in greater detail by his daughter and celebrated psychoanalyst in her own right, Anna Freud [Table 1].

Therefore, from the outset, I would like to highlight and thank the immense trust, placed upon our shoulders by our patients, to wield the metaphorical and the actual scalpel. It is a privilege and a deeply humbling experience that we should not allow ourselves to take for granted.

|

Primitive defence mechanisms |

|

Avoidance: Dismissing thoughts or feelings that are uncomfortable or keeping away from people, places, or situations associated with uncomfortable thoughts or feelings. This defence mechanism may be present in post-traumatic stress disorder, where one avoids the location of a traumatic motor vehicle accident or avoids driving completely. Denial: Dismissing external reality and instead focusing on internal explanations or fallacies and thereby avoiding the uncomfortable reality of a situation. This defence mechanism may be present in a patient who denies the existence of a serious medical diagnosis like cancer. Identification: The reproduction of behaviours observed in others, such as a child developing the behaviour of his or her parents without conscious realisation of this process, or a resident adopting the mannerism of his or her attending surgeon. Identification is also known as introjection. Projection: Attributing one’s own maladaptive inner impulses to somebody else. For example, someone who commits an episode of infidelity in their marriage may then accuse their partner of infidelity or may become more suspicious of their partner. Repression: Subconsciously blocking ideas or impulses that are undesirable. This defence mechanism may be present in someone who has no recollection of a traumatic event, even though they were conscious and aware during the event. |

|

Higher level defence mechanisms |

|

Anticipation: The devotion of one’s effort to solving problems before they arise. This defence mechanism may be present in a surgeon who prepare a Plan B in case of an anticipated complication. Displacement: Transferring one’s emotional burden or emotional reaction from one entity to another. This defence mechanism may be present in a surgeon who has a stressful day at work and then lashes out against their family at home (sorry!). Intellectualisation: The development of patterns of excessive thinking or over-analysing, which creates a distance from one's emotions. For example, someone diagnosed with cancer does not show emotion after the diagnosis but instead starts to research every source they can find about the illness. Rationalisation: The justification of one’s behaviour through attempts at a rational explanation. This defence mechanism may be present in someone who steals money but feels justified in doing so because they needed the money more than the person from whom they stole. Suppression: Consciously choosing to block ideas or impulses that are undesirable, as opposed to repression, a subconscious process. This defence mechanism may be present in someone who has intrusive thoughts about a traumatic event but pushes these thoughts out of their mind. |

Table 1: Defence mechanisms, adapted from Defense Mechanisms by Bailey and Pico14.

The patient

The psychology of the patient is shaped by his or her personality, health, education, socio-economic level, cultural and religious beliefs. In the preceding section, we have already discussed trust and vulnerability at great length. Another consideration is patient expectation, which has changed over time and will continue to change. This is the nature of progress, and we are in some ways the victim of our own success. Take arthroplasty for example, patients now expect a largely active life after joint replacement surgery15 and most reasonably expect to return to golf, swimming, and running. My wife (who is a GP) tells me a story of a gentleman in her clinic recently, who was very crossed and upset when told that he might have arthritis in his knees and perhaps that was the reason his knees hurt. “But doctor, I go to the gym twice a week, and I plan to run the London marathon for my 85th birthday, I can’t possibly have arthritis!” He protested vehemently.

So, we now face a population with vastly different expectations, and perhaps less willing to accept the restrictions on an active life, through disease or surgery or both, to the one that was operated by the generations of surgeons before us. This means that we may have to look at the way of we approach surgery, not only in terms of implant and technique, but also the management of expectation. What is a good outcome? What is a realistic outcome? Who defines a good outcome? If a partial knee replacement allows one to be pain free, return to sports or work, and enjoy life in general, but only last five years; is that a good or bad outcome? Does an early revision automatically equal failure? This is as much a philosophical question as it is a clinical one. Instinctively one must argue that it is the patient’s perspective that matters most in this regard. This touches on the fundamental principle of autonomy in medicine. Therefore, we must enable our patients to be better informed and more empowered to participate in the decision-making process.

Understanding and addressing the psychological aspects of being a patient is essential for delivering patient-centred care. It involves recognising the unique needs and concerns of individuals and goes beyond the purely technical aspects of executing an operation.

The surgeon

If there is little written about the psychology of a patient, less still is written about the psychology of a surgeon; yet understanding it is vitally important. Our patients, in one sense, only exist in the imagination of our own mind; and like everything else, this is coloured by our personality, experience, education, bias, beliefs, and our own interaction with the patient. Therefore, it stands to reason, that to truly understand our patients, we must seek to understand ourselves first and foremost. Steven Covey put it simply as “first seek to understand, then be understood”16.

The psychology of being a surgeon is complex and multi-faceted – we accept there is no one-size to fit all and different individual styles each have their merits. However, there are some common threads. The first theme is emotional resilience – there is no doubt that surgeons often work under extreme pressure, make life-or-death decisions, and perform complex procedures that require immense precision and enormous mental focus. The old saying of “eyes of a hawk, hands of a lady, and heart of a lion” still rings true in many ways. This goes hand in hand with emotional resilience, with coping mechanisms to remain appropriately distanced to the stress of the environment, make the right call in the heat of the moment, and avoid burn-out in the long run. The second is leadership – we can’t operate alone; without the dedication of our teams including nurses, physiotherapists, anaesthetists, and other colleagues, we simply can’t do our job. The most successful surgeons are also often the most effective leaders. The final theme is empathy and compassion – whilst some emotional detachment is desirable for us to make rational and calculated decisions, all of us came into this game with the intention of doing good. We must not lose the empathy and compassion for our patients – even when surgery goes wrong17, or the outcome is not what surgeons or patients expected. There is invariably value in empathy and compassion, which is the basis for effective communication. Evidence suggests that effective and open communication is the single most influential factor when patients choose to make a complaint18. Long after patients forget the minutiae of the post operative instructions or even the name of their surgeon, they may remember the kindness of your words and the gentleness of your tone. Memory is coloured by emotion, at a time of uncertainty and fear, there is opportunity to be perceived in a multitude of ways.

The psychological requirements for an effective surgeon, therefore, involves a blend of intellect, skill, emotional strength, and effective communication, all while navigating the high-stakes environment of surgical care.

Partnership

Beauchamp and Childress19,20 described four prima facie principles in medicine: beneficence (in the best interest of the patient), nonmaleficence (do no harm), autonomy (patients have a right to make decisions about their health), and justice (fairness). Any attempt to analyse or describe surgeon-patient relationship must be grounded in those principles.

On an individual level, there are a number of interesting psychological processes between a surgeon and their patient. One such process is that of transference and countertransference21. These concepts are founded in the psychodynamic theory and are frequently considered by therapists when seeking to understand their relationship with a patient. Transference refers to the subconscious transfer of feelings from a past relationship to the present relationship with the therapist. For example, the surgeon may subconsciously remind the patient of a teacher (an authoritative figure) that was kind and supported him or her in school; or an old boss who criticised and undermined him or her at work. This unconscious transfer of feelings and attitudes may result in the patient relating or behaving in different ways, either positively or negatively, towards the surgeon. Countertransference would refer to the unconscious reaction of the surgeon to the transference. For example, the patient unconsciously treating the surgeon like that kind and supportive teacher may invoke feelings of paternalism. Perhaps being treated as if one was an unhelpful boss might generate feelings of resentment in the surgeon. These reactionary feelings or attitudes understandably affect how the surgeon interacts with the patient. In psychodynamic theory this process can help to explain why an individual may repeat certain relationship patterns throughout their life – they may be unconsciously influencing others into assuming roles from their past through transference and countertransference. These interactions can play out in countless different ways. However, it is invariably an unconscious process. This requires that deliberate consideration and thought be given to recognise or understand it. Perhaps there is value as a surgeon to be aware of such interactions. Could this lead to better communication or understanding of a patient’s perspective? This may enable us to ask questions such as “how does this patient make me feel?”, “why does this patient make me feel this way?”, and “are these feelings influencing the way I interact with them?” This perhaps will allow us greater insight into our own countertransference and so logically the ability to temper such reactions, even if we couldn’t possibly know it is happening due to us sharing the mannerisms and the hairstyle of their old boss!

On a theoretical level, Emanuel and Emanuel22 described four models of doctor-patient relationships, from Paternalistic Model on one end of the spectrum, to Informative (Consumer) Model on the other end of the spectrum. Whilst current thinking has moved away from the traditional Paternalistic Model (surgeon knows best), there is now an increasingly tendency to treat patients as clients and surgeons as mere service providers or technicians. The Informative (Consumer) Model as described by Emanuel and Emanuel, which is perhaps a reflection of the pervasive influence of consumerism in everyday society, fundamentally undermines a healthy, balanced surgeon-patient relationship built on mutual trust and respect, must be resisted. The Deliberative Model – where doctors and patients are equal partners that share the decision-making process – has perhaps the best available evidence for patient satisfaction. It however implies that patients must own the responsibility for their health. A relevant example is obesity. Obesity clearly impacts on surgical morbidity and complication23,24. This poses an ethical dilemma – is it discriminatory to refuse surgery on the basis of weight alone? How does this fit in with the body positive movement that is part of our society’s burgeoning embrace with diversity and inclusivity? On the other hand, do we not also have a social responsibility to allocate a finite resource (healthcare) to deliver the best possible outcome for the largest group of patients? In which case, might high-risk low-benefit surgery (joint replacements in morbidly obese patients, or lung transplants for smokers, or liver transplants for alcoholics) be considered unethical? Going back to the issue of obesity - should patients take ownership? Are they in a position to take ownership? Obesity is closely linked with poverty and low socio-economic attainment; therefore, patients may not have access to the resources (healthy diet, gym membership) to attain a normal weight. As one might appreciate, the moral issues at hand soon become entangled in complex, societal issues with no obvious solutions.

Conclusion

Understanding the psychology factors at play within ourselves, our patients and our interactions can make us better surgeons. It may influence outcome and satisfaction, both for us and our patients. Patients are our best resources, and we should be humble enough to learn from them. This essay is not about providing clearcut answers or ask rhetorical questions – I have found more value and insight with the awareness, consideration, and reflection of this topic. I sincerely hope my intrigue and curiosity will be shared by others.

References

- Doherty AM, Gaughran F. The interface of physical and mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(5):673-82.

- Naylor C, Das P, Ross S, Honeyman M, Thompson J, Gilburt H, et al. Bringing together physical and mental health: a new frontier for integrated care. London: The King's Fund; 2016.

- Vajapey SP, McKeon JF, Krueger CA, Spitzer AI. Outcomes of total joint arthroplasty in patients with depression: A systematic review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;18:187-98.

- Lopez-Olivo MA, Ingleshwar A, Landon GC, Siff SJ, Barbo A, Lin HY, et al. Psychosocial Determinants of Total Knee Arthroplasty Outcomes Two Years After Surgery. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(10):573-81.

- Ahn A, Snyder DJ, Keswani A, Mikhail C, Poeran J, Moucha CS, et al. The Cost of Poor Mental Health in Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(12):3432-6.

- Nguyen UDT, Perneger T, Franklin PD, Barea C, Hoffmeyer P, Lübbeke A. Improvement in mental health following total hip arthroplasty: the role of pain and function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):307.

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2515-24.

- Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(2):81-8.

- Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P, Wriedt C, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):557-68.

- Guo MY, Crump RT, Karimuddin AA, Liu G, Bair MJ, Sutherland JM. Prioritization and surgical wait lists: A cross-sectional survey of patient's health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 2022;126(2):99-105.

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Horvath AO. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2018;55(4):316-40.

- GMC. Good Medical Practice. Available at: www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/professional-standards-for-doctors/good-medical-practice. [last accessed on 18 Feb 2024].

- Cramer P. Understanding Defense Mechanisms. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2015;43(4):523-52.

- Bailey R PJ. Defense Mechanisms. Updated 2023 May 22. StatPearls Publishing. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559106. [last accessed on 18 Feb 2024].

- Lester D, Barber C, Sowers CB, Cyrus JW, Vap AR, Golladay GJ, et al. Return to sport post-knee arthroplasty: an umbrella review for consensus guidelines. Bone Jt Open. 2022;3(3):245-51.

- Covey S. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Simon & Schuster UK; 2020.

- GMC. The Professional Duty of Candour. Available at www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/professional-standards-for-doctors/candour---openness-and-honesty-when-things-go-wrong/the-professional-duty-of-candour. [last accessed on 18 Feb 2024].

- MPS. YouGov Survey: Communication a key trigger of GP complaints. 2017. Available at: www.medicalprotection.org/uk/articles/yougov-survey-communication-a-key-trigger-of-gp-complaints. [last accessed on 18 Feb 2024].

- Gillon R. Defending 'the four principles' approach to biomedical ethics. J Med Ethics. 1995;21(6):323-4.

- Beauchamp and Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics: 5th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Weiss H. The enigma of transference. Freud's discovery and its repercussions. Int J Psychoanal. 2023;104(4):679-90.

- Emanuel and Emanuel. Four Models of the Physician-Patient Relationship. JAMA; vol 267, no 161992.

- Curtis A, Manara J, Doughty B, Beaumont H, Leathes J, Putnis SE. Severe obesity in total knee arthroplasty occurs in younger patients with a greater healthcare burden and complication rate. Knee. 2023;46:27-33.

- Martinez R, Chen AF. Outcomes in revision knee arthroplasty: Preventing reoperation for infection Keynote lecture - BASK annual congress 2023. Knee. 2023;43:A5-A10.