The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on ARCP outcomes issued to trainees in trauma and orthopaedic surgery

By Charlie Bartera, David Humesb, Deepa Bosec and Jon Lunda

aDivision of Medical Sciences and Graduate Entry Medicine, University of Nottingham

bDivision of Epidemiology and Public Health, and Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre, University of Nottingham

cDepartment of Trauma and Orthopaedics. Queen Elizabeth Hospital, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham

Introduction

Since being declared a pandemic in March 20201, Covid-19 has disrupted the provision of surgical healthcare worldwide. Repercussions can be seen in the provision of surgical training, particularly in specialties with a heavy elective component such as trauma and orthopaedic surgery2,3. The literature describes the various aspects of these negative effects4, from reduction in operating room time5,6, reduction in other clinical environment exposures7,8, detriments to trainee mental health9,10, and impacting the holding of exams and other necessary learning events3,11.

UK Surgical training follows outcome based curricula written by the Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST)12 and approved by the General Medical Council (GMC). Records of each trainees’ training and assessment are kept on a training management platform: The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme (ISCP)13. Trainee operative cases are recorded in the Surgical eLogbook14. The succession from one training stage to another is recorded at an Annual Review of Competency Progression (ARCP) on ISCP by a panel of surgical educators, against benchmarks described in the surgical curriculum. Several classes of outcome can be awarded at ARCP, each denoting the panels advice on the trainee’s progression for the next year (or less if their continued development is deemed to require further input). Possible outcomes are shown in Table 1.

In recognition of the significant challenges to progression imposed by Covid-19 two new 'non-standard' outcomes were introduced in 2020 as derogations to the eighth edition of the 'Gold Guide'15,16 (numbered 10.1 and 10.2, Table 1). These two new outcomes indicated 'no fault' on the part of the trainee, i.e. lack of progression was a fault of the training environment. A trainee awarded one would not be prevented from sitting postgraduate examinations, or taking out of programme leave, as they would be with other non-standard outcomes.

The awarding of non-standard outcomes has been linked in previous studies to some of the protected personal characteristics of the trainee17, a situation the surgical community is committed to addressing. Orthopaedic surgery remains a male-dominated area of practice, with only 28.5% of doctors in training, and 7.4% of consultants, female as of 31st May 202118. As such it is a specialty where attention to differential attainment is incredibly important.

The primary aim of this study was to assess the impact of the pandemic on trainee progression through higher specialty training in trauma and orthopaedic surgery in the UK. Secondary aims include the investigation of use of the new Covid-19 specific ARCP outcomes, and differential effects on non-standard ARCP outcome awarding by demographic factors, working pattern, and region.

|

Outcome |

ARCP Outcomes |

Description |

|

1 |

Progression Advised (Standard/Progressive) |

Satisfactory progress: achieving progress and the development of competences at the expected rate. |

|

2 |

Developmental of Capabilities Required (Non-Standard/Developmental) |

Development of specific competences required: additional training time not advised. |

|

3 |

Developmental of Capabilities Required (Non-Standard/Developmental) |

Inadequate progress: additional training time advised. |

|

4 |

Released from Programme (Non-Standard/Developmental) |

Released from training programme: with or without specified competences. |

|

5 |

Incomplete Evidence (Non-Standard/Temporary) |

Incomplete evidence presented: additional training time may be required. |

|

6 |

Satisfactory Completion of Training Programme (Standard/Progressive) |

Gained all required competences: will be recommended as having completed the training programme. |

|

7 |

Fixed Term Posts |

Split into 1-4 as per there numeric counterparts in other categories. |

|

8 |

Out of Programme |

Out of programme for clinical experience, research, or a career break. |

|

10 |

Covid-19 Specific Outcomes (Non-Standard/Developmental) |

Acquisition of competencies delayed due to Covid-19. Split into 10.1 – no additional training time advised, and 10.2 – additional training time advised. |

Table 1: Possible ARCP Outcomes; adapted from the Gold Guide (Conference of Post Graduate Medical Deans of the UK 2019, 2020)15,16 and C Hope17. Outcomes were grouped as 'Standard' (1 and 6) and 'Non-Standard' (2, 3 and 10).

Methods

Study design

This was a longitudinal cohort study using anonymised trainee data taken from the ISCP training management system. It was performed in line with 'Strengthening Reporting in Observational Studies in Epidemiology' (STROBE) guidelines19.

Cohort derivation

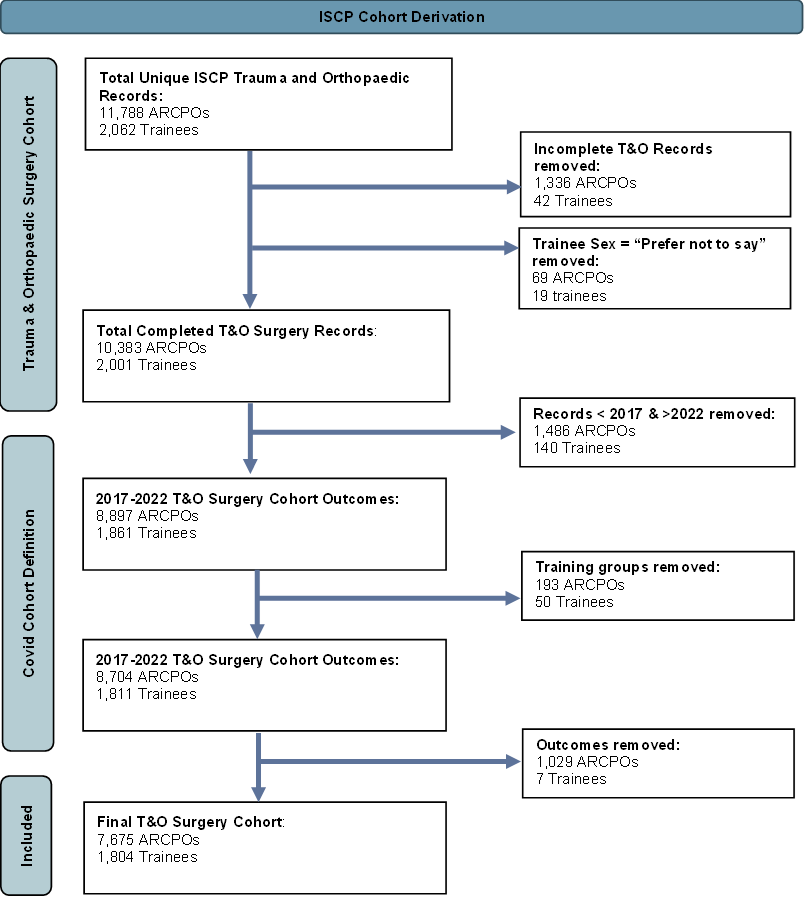

The cohort consisted of all UK higher speciality trainees in trauma and orthopaedic surgery with an ARCP outcome recorded between January 2017 and December 2022. All ARCP outcomes with complete data were included. The smaller populations of trainees who did not disclose their sex (19 trainees, 69 ARCP outcomes), and those who had left training without achieving CCT (45 trainees, 171 ARCP outcomes) were also excluded as their size precludes reliable statistical inferences being drawn from them. Excluded records are detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cohort Derivation Flowchart. ARCPO: Annual Review of Competency Progression Outcome, ISCP: Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme, T&O: Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, Excluded Training Groups include Fixed term posts, locum appointed for training, those who left training without CCT, and post certificate of completion of training. Excluded outcomes include 'Released from Training Programme' (outcome 4), incomplete evidence provided (outcome 5), and 'Out of Programme' (outcome 8).

Exposure variables

Exposure variables included year of ARCP, trainee sex and age group, trainee working pattern, and stage of training. Age was grouped into those under 30 on starting their higher specialty training (HST), and those over 30. For working pattern groupings ARCPs were divided into those issued to fulltime trainees, and those issued to trainees who were either currently less than fulltime (LTFT) or had worked LTFT previously. A period of LTFT working was assumed to affect more than just the chronologically closest ARCP. Training status at point of data extraction (February 2023, provided as 'still in training' and 'achieved CCT' groups) was used as an indicator of stage of training during the Covid-19 effected years. Those in the 'still training' group were assumed to be earlier in their training during the pandemic, with those having 'achieved CCT' by February 2023 likely in the late stages of training at this point).

Outcome measure

ARCP outcome was the primary outcome measure. Outcomes were grouped into 'standard' (outcomes 1 and 6), 'non-standard without extra training time' (outcomes 2 and 10.1), and 'non-standard with extra time' (outcomes 3 and 10.2). Outcome 5s were excluded from analysis, as their use is as a stay when a trainee needs to provide further evidence of their progress before a formal outcome can be awarded. Outcome 8s; 'out of programme' were also excluded as during periods of 'OOP' trainees are not expected to contribute evidence of in programme progression. 'Removal from the training programme' and 'fixed term placement' (outcomes 4 and 7) were infrequently used (8 and 47 respectively), and thus excluded. Ungrouped outcomes were used to examine the use of Covid-19 outcomes (10.1 and 10.2).

Statistical analysis

Univariable logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the association between potential risk factors and non-standard outcome at ARCP. Variables producing a statistically significant (p <0.05) result were carried forward to build a multivariate logistic regression model to assess the strength of associations. Trainee gender and age group were considered a priori confounders. Individuals providing incomplete responses were excluded from the analyses to maintain a stable denominator. All statistics were performed using R Studio Version 2023.06.2+56120.

When comparing the effects of year on ARCP outcome 2017 was used as the comparator year. On analysing by region London, as the region with the largest trainee population, was used as the comparator.

Results

This analysis included 7,675 ARCP outcomes issued to 1,417 HSTs in trauma and orthopaedic surgery between January 2017 and December 2022, (Table 2). Female trainees accounted for 21.5% (387) of the population. The population was evenly divided between older and younger trainees, with 50.6% (912) of the group under 30 on starting HST. Fifty-seven-point five percent (1,038) of our cohort had achieved CCT by February 2023 (hence would have been in the later stages of HST during the pandemic).

|

Demographic Groups

|

Trainees - n (%) |

Total = 1,804 |

|

|

Sex |

Male |

Female |

|

|

1,417 (78.5%) |

387 (21.5%) |

||

|

Age Group |

Under 30 |

Over 30 |

|

|

912 (50.6%) |

892 (49.4%) |

||

|

Training Status as of Feb 2023 |

In Training |

Achieved CCT |

|

|

766 (42.5%) |

1,038 (57.5%) |

||

|

Demographic Groups |

ARCP Outcomes Issued to Group – n (%) Total = 7,675 |

||

|

Sex |

Male |

Female |

|

|

|

6,002 (78.2%) |

1,673 (21.8%) |

|

|

Age Group |

Under 30 |

Over 30 |

|

|

|

3,842 (50.1%) |

3,833 (49.9%) |

|

|

Training Status as of Feb 2023 |

In Training |

CCT |

|

|

|

2,999 (39.1%) |

4,676 (60.9%) |

|

|

Working Pattern |

Fulltime |

LTFT/Post LTFT |

|

|

|

7,102 (92.5%) |

573 (7.5%) |

|

Table 2: Demographics of Trauma and orthopaedic trainees registered on ISCP, & ARCP outcomes issued by demographic group. Totals do not include missing data for each group.

Whole cohort statististis

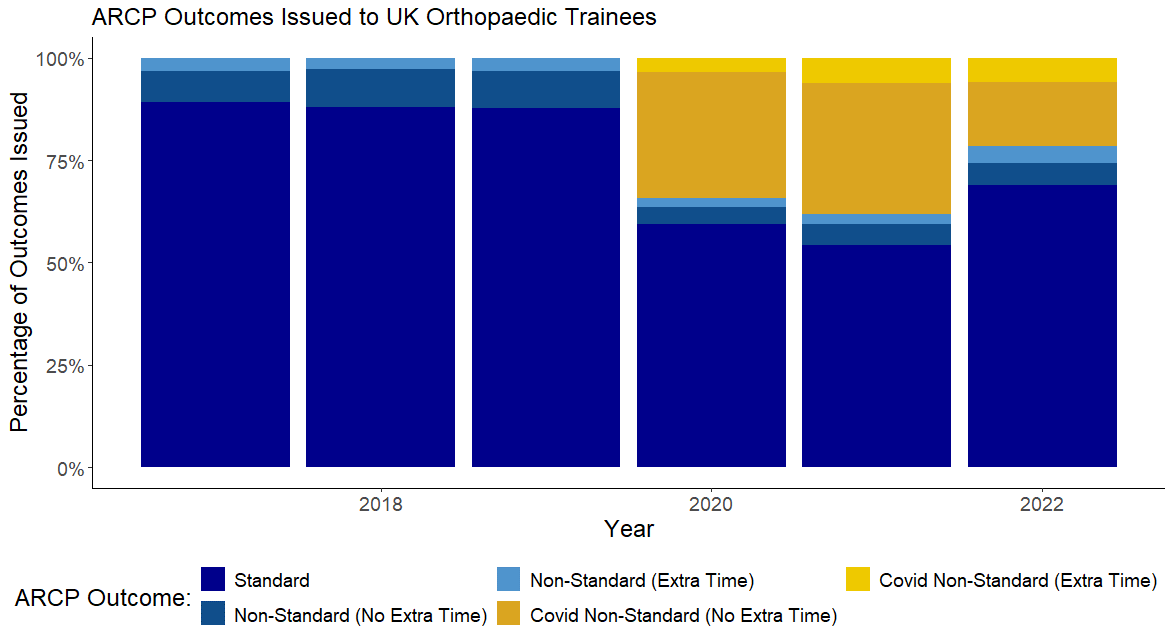

Prior to the pandemic standard outcomes ranged between 87.8% and 89.1% (Figure 2). Standard outcomes reduced significantly in 2020 and had not fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2022 (Figure 2). Non-standard outcomes advising extra time in training (Outcomes 3 and, once available, 10.2) rose steadily after 2020, from a pre-pandemic average of 3.2% to 10.0% of outcomes issued in 2022.

Following adjustment for sex, age group, stage of training, and deanery, the Odds Ratio (AOR) of receiving a non-standard outcome was found to peak at 5.47 (95% CI: 4.39-6.81, P <0.001) in 2021 (Table 3).

Figure 2: Trends in Grouped ARCP outcomes received by Trauma and orthopaedic surgery trainees by year. Total outcomes by year; 2017 = 1,247; 2018 = 1,320; 2019 = 1,274; 2020 = 1,306; 2021 = 1,257; 2022 = 1,229.

Trainee protected characteristics

The percentage of non-standard outcomes issued to female trainees was 27.2% (455 outcomes) compared to 24.9% (1,493 outcomes) in the male trainee population. Female trainees did not have an increased odds ratio of receiving a non-standard outcome at ARCP compared to their male colleagues (Adjusted OR 1.10 (0.97 – 1.26), P = 0.149).

Trainees who were older on starting their higher specialty training were more likely to receive non-standard outcomes than their younger colleagues (27.1% of 1,039 outcomes vs. 23.7% of 909 outcomes). After adjusting for other factors older trainees were 1.4 times more likely to receive a non-standard outcome (AOR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.24-1.56, P<0.001) as shown in Table 3.

186 trainees in this cohort had worked at least one LTFT placement, and a total of 573 LTFT/post LTFT ARCP outcomes were analysed. Having worked a less than fulltime (LTFT) placement was not associated with an increased likelihood of receiving a non-standard outcome (unadjusted OR 1.17, 95% CI: 0.97-1.42, P = 0.100, as per Table 3).

|

|

N Standard / Non-Standard |

% Non-Standard |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P Value |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

P Value |

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2017

|

1,111 / 136 |

10.9% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

2018 |

1,162 / 158 |

12.0% |

1.11 (0.87 -1.41) |

0.420 |

1.05 (0.82 – 1.34) |

0.705 |

|

2019 |

1,140 / 159 |

12.2% |

1.14 (0.89 -1.45) |

0.322 |

0.99 (0.77 – 1.27) |

0.925 |

|

2020 |

757 / 517 |

40.6% |

5.58 (4.52 – 6.88) |

<0.001 |

4.76 (3.83 – 5.93) |

<0.001 |

|

2021 |

710 / 596 |

45.6% |

6.86 (5.57 – 8.45) |

<0.001 |

5.47 (4.39 – 6.81) |

<0.001 |

|

2022 |

847 / 382 |

31.1% |

3.68 (2.97 – 4.57) |

<0.001 |

2.60 (2.06 – 3.28) |

<0.001 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male

|

4,509 / 1,493 |

24.9% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

Female |

1,218 / 455 |

27.2% |

1.12 (1.00 - 1.28) |

0.057 |

1.10 (0.97 – 1.26) |

0.149 |

|

Age on Starting HST |

||||||

|

Under 30 |

2,933 / 909 |

23.7% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

Over 30 |

2,794 / 1,039 |

27.1% |

1.19 (1.08 – 1.33) |

<0.001 |

1.39 (1.24 – 1.56) |

<0.001 |

|

Working Pattern |

||||||

|

Fulltime

|

5,316 / 1,786 |

25.1% |

1 |

|

|

|

|

LTFT |

411 / 162 |

28.3% |

1.17 (0.97 - 1.42) |

0.100 |

|

|

|

Training Status in February 2023 |

||||||

|

In Training

|

1,934 / 1,065 |

35.5% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

Achieved CCT |

3,793 / 883 |

18.9% |

0.42 (0.38 – 0.47) |

<0.001 |

0.60 (0.53 – 0.67) |

<0.001 |

Table 3: Trauma and orthopaedic surgery: Use of non-standard ARCP outcomes: Univariate and multiple logistic regression. Total n = 3,809.

Stage of training

Those remaining 'In Training' in February 2023 were taken as the baseline group for analysing effects of point in training on ARCP outcome (Table 3). Compared to these, trainees who had completed the training programme by February 2023 (CCT group) were significantly less likely to receive a non-standard ARCP outcome with an adjusted OR of 0.60 (95% CI:0.53-0.67, P<0.001)

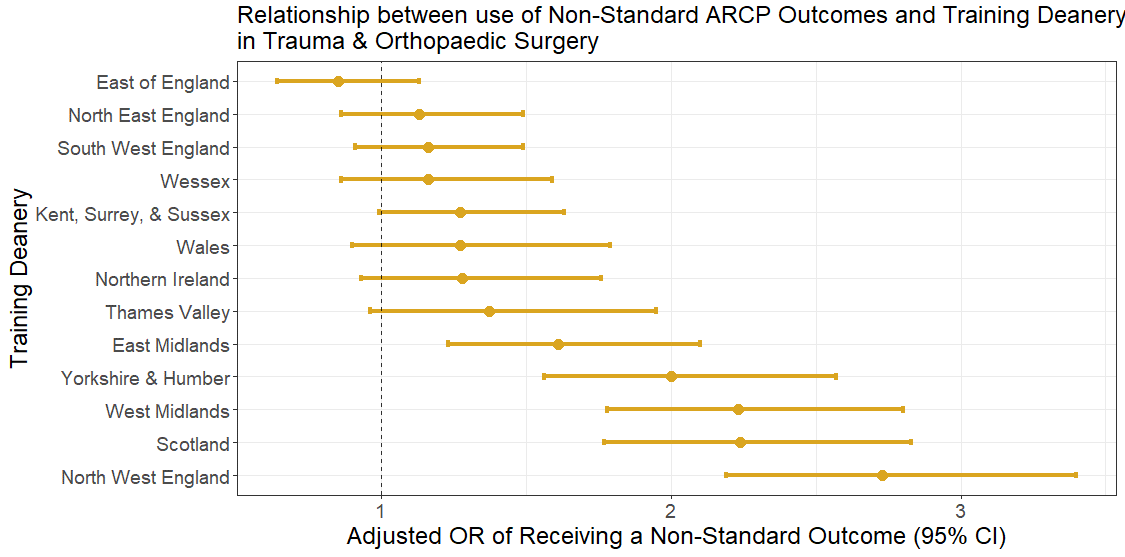

Deanery

The adjusted odds of receiving a non-standard outcome based on training region are shown in Figure 3. Five areas were found to have statistically significantly different AORs for non-standard ARCP outcome from the reference region (London). From lowest to highest adjusted OR they were: the East Midlands; (AOR 1.61, 95% CI:1.23-2.10), Yorkshire and the Humber (AOR 2.00, 95% CI:1.56-2.57), the West Midlands (AOR 2.23, 95% CI: 78-2.70), Scotland (AOR 2.24, 95% CI:1.77-2.83), and North-West England (AOR 2.73, 95% CI:2.19-3.40).

Figure 3: Orthopaedic surgery higher specialty trainees’ ARCP outcomes: Adjusted odds ratios of receiving a Non-standard outcome by region relative to London.

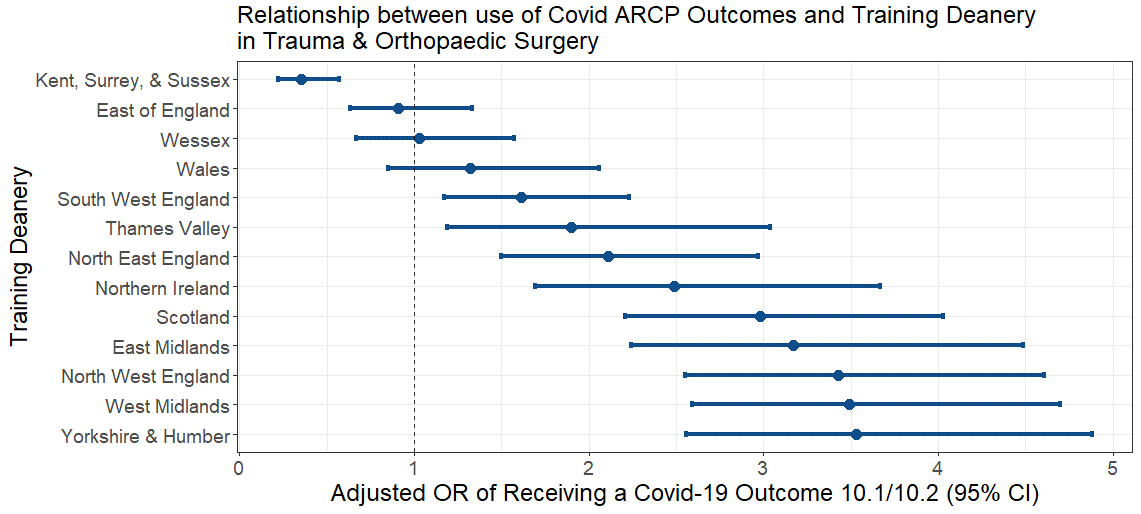

Figure 4: Orthopaedic surgery higher specialty trainees’ ARCP outcomes: Adjusted odds ratios of receiving any Covid-19 outcome (10.1-10.2) by deanery, relative to London.

Covid-19 outcomes

Following their introduction, Covid-19 outcomes (10.1 and 10.2) made up 34.3% (437) and 38.3% (500) of all outcomes issued in 2020 and 2021 (Table 4). Their use dropped in 2022 to a proportion of 21.5% (264 outcomes). The adjusted OR of receiving a Covid-19 outcome in 2022 was 0.39 (compared to 2017 ,95% CI: 0.32-0.47, P <0.001).

Neither trainee sex nor age were associated with an increased OR of receiving a Covid-19 outcome (Table 4). Working an LTFT placement was protective against a Covid-19 outcome, as was being later in training during the pandemic (CCT by February 2023 group), with adjusted ORs of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.57-0.96, P= 0.024) and 0.48 (95% CI: 0.41-0.56, P <0.001) respectively (Table 4).

Significant variation in geographical use of Covid outcome use was demonstrated, even following adjustment for other variables (Figure 4). Trainees in only one deanery carried a lower AOR of receiving a Covid-19 outcome than those in London (Kent, Surrey, and Sussex Deanery at 0.35, 95% C 0.22- 0.57). Two deaneries showed no significant difference in AOR for Covid-19 outcome use compared to London; the east of England (AOR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.63- 1.33) and Wales (AOR 1.32, 95% CI: 0.85-2.06). The remaining 10 deaneries all demonstrated a significant increase in AOR of receiving a Covid-19 outcome.

|

|

N ARCP Standard/ 10.1/10.2 |

% Outcome 10.1 /10.2 |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) 10.1 or 10.2 |

P Value |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) 10.1 or 10.2 |

P Value |

|

Year |

||||||

|

2020 |

837 / 393 / 44 |

30.8% / 3.5% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

2021 |

806 / 418 / 82 |

32.0% / 6.3% |

1.19 (1.01 – 1.40) |

<0.001 |

1.04 (0.88 – 1.23) |

0.654 |

|

2022 |

965 / 192 / 72 |

15.6% / 5.9% |

0.52 (0.44 – 0.63) |

<0.001 |

0.39 (0.32 – 0.47) |

<0.001 |

|

Sex |

||||||

|

Male |

2,041 / 769 / 142 |

26.1% / 4.8% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

Female |

567 / 234 / 56 |

27.3% / 6.5% |

1.15 (0.97 – 1.35) |

0.103 |

1.17 (0.98 – 1.39) |

0.085 |

|

Age on Starting HST |

||||||

|

Under 30 |

1,291 / 545 / 82 |

11.0% / 3.1% |

1 |

|

- |

- |

|

Over 30 |

1,317 / 458 / 116 |

24.2% / 6.1% |

0.90 (0.78 – 1.02) |

0.125 |

- |

- |

|

Working Pattern |

||||||

|

Fulltime |

2,307 / 926 / 175 |

27.2% / 5.1% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

LTFT/ post LTFT |

301 / 77 / 23 |

19.2% / 5.7% |

0.70 (0.55 – 0.88) |

0.003 |

0.74 (0.57 – 0.96) |

0.024 |

|

Training Status in February 2023 |

||||||

|

In Training |

1,411 / 704 / 81 |

32.1% / 3.7% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

Achieved CCT |

1,197 / 299 /117 |

18.5% / 7.3% |

0.62 (0.54 – 0.72) |

<0.001 |

0.48 (0.41 – 0.56) |

<0.001 |

|

Region |

N ARCP Standard/ 10.1/10.2 |

% Outcome 10.1 /10.2 |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) 10.1 or 10.2 |

P Value |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) 10.1 or 10.2 |

P Value |

|

London |

468 / 77 / 48 |

13.0% / 8.1% |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

East Midlands |

123 / 63 / 28 |

29.4% / 13.1% |

2.77 (1.98 – 3.87) |

<0.001 |

3.17 (2.24 – 4.49) |

<0.001 |

|

East of England |

197 / 44 / 6 |

17.8% / 2.4% |

0.95 (0.66 – 1.37) |

0.852 |

0.91 (0.63 – 1.33) |

0.626 |

|

Kent, Surrey, & Sussex |

244 / 16 / 6 |

6.0% / 2.3% |

0.34 (0.21 – 0.54) |

<0.001 |

0.35 (0.22 – 0.57) |

<0.001 |

|

NE England |

163 / 68 / 12 |

28.0% / 4.9% |

1.83 (1.32 -2.56) |

<0.001 |

2.11 (1.50 – 2.97) |

<0.001 |

|

NW England |

219 / 135 / 22 |

35.9% / 5.9% |

2.68 (2.02 – 3.57) |

<0.001 |

3.43 (2.55 – 4.61) |

<0.001 |

|

SW England |

225 / 80 / 9 |

25.5% / 2.9% |

1.48 (1.08 – 2.03) |

<0.001 |

1.61 (1.17 – 2.23) |

0.004 |

|

Thames Valley |

80 / 26 / 6 |

23.2% / 5.4% |

1.50 (0.95 – 2.36) |

<0.001 |

1.90 (1.19 – 3.04) |

0.007 |

|

West Midlands |

182 / 152 / 12 |

43.9% / 3.5% |

3.37 (2.53 – 4.50) |

<0.001 |

3.49 (2.59 – 4.70) |

<0.001 |

|

Wessex |

137 / 27 / 9 |

15.6% / 5.2% |

0.98 (0.65 – 1.49) |

1.000 |

2.85 (1.83 – 4.46) |

<0.001 |

|

Yorkshire & the Humber |

146 / 93 / 27 |

35.0% / 10.2% |

3.07 (2.52 – 4.20) |

<0.001 |

3.53 (2.56 – 4.88) |

<0.001 |

|

Northern Ireland |

112 / 57 / 1 |

33.5% / 0.6% |

1.94 (1.33 – 2.82) |

<0.001 |

2.49 (1.69 – 3.67) |

<0.001 |

|

Scotland |

210 / 137 / 5 |

38.9% / 1.4% |

2.53 (1.89 – 3.38) |

<0.001 |

2.98 (2.21 – 4.03) |

<0.001 |

|

Wales |

102 / 28 / 7 |

20.4% / 5.1% |

1.28 (0.83 – 1.98) |

0.253 |

1.32 (0.85 – 2.06) |

0.215 |

Table 5: Trauma and orthopaedic surgery: Regional use of Covid-19 ARCP outcomes: Univariate and multiple logistic regression. Total n = 3,809.

Discussion

This analysis quantifies the significant disruption in training faced by UK Orthopaedic trainees during Covid. In 2020 HSTs were 4.76 times more likely to be awarded a non-standard outcome at ARCP compared to 2017. This increased need for non-standard outcome use persisted to the end of the data collection period. Unlike their peers in general surgery21 the orthopaedic populations’ chances of receiving a non-standard outcome were not increasing prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Female trainees are not more likely to receive non-standard outcomes compared to their male counterparts. This is encouraging, especially considering the well-documented challenges women face in the specialty, as detailed in Ahmed et al.'s comprehensive literature review on the obstacles confronting women in orthopaedics22. Predictive modelling by Acuña et al. indicates that achieving gender parity in orthopaedics in the US may take as long as 326 years23. However, it is reassuring that, at least in the UK, ARCP assessments do not contribute to the significant underrepresentation of senior women in the field. That said, these findings do not diminish the many areas where female trainees continue to encounter bias. Hutchinson’s iterative thematic analysis of trainees' experiences24 underscores issues such as epistemic injustice and stereotyped expectations as critical barriers to the advancement of female trainees.

Older trainees are almost 40% more likely to receive a non-standard outcome, even after adjusting for other factors. This has been observed in other cohort studies on broader surgical populations21,25, and warrants further scrutiny of potential causes. Identifying causes for observed differences such as this one will be critical to offering targeted support and ensuring equitable training opportunity.

Trainees later in their training during the pandemic were 40% less likely to receive non-standard outcomes overall suggesting that they were less susceptible to the negative effects of the pandemic than their junior colleagues. The opposite effect was seen in our previous paper looking at ARCP outcomes in the General Surgery HST population21. This may be due to differential use of non-standard outcomes between these two specialties, or different approaches to managing departmental resources and training opportunities for later stage trainees.

The use of the Covid-19 specific non-standard outcomes was not consistent across the UK. This may suggest that the JCST guidance on their use was either not uniformly understood, or not uniformly applied. A considerable part of the rise in awarding of non-standard outcomes was driven by outcome 10’s, suggesting some success in the JCST’s strategy for mitigating the negative effects of the pandemic. Introducing outcomes that could simultaneously reflect the need for additional targeted training or time for a trainee, without preventing them from pursuing progressional benchmarks such as time out of programme, or exam attempts will have benefited many.

This study adds to an ongoing descriptive picture of differential attainment in surgical training. Work so far has focused on the complex and multifaceted interplay of gender25,26, race26-28, and socioeconomic status25,26,29. As our understanding of these elements expand so to do our opportunities to develop intersectional strategies to support trainees as part of the post Covid-19 recovery of training. The results of this study suggest that these strategies may be of most benefit to the older trainee community.

The use of ISCP records contributes both strengths and limitations to this study. As a prospectively filled, user-edited, central training portfolio, the ISCP provides raw data directly from the trainees themselves. As such, it provides an incredible direct access resource to the contemporary training experience. As its use is essentially mandatory, it also provides access to the widest possible trainee population. However, as it is not a managed database, the ISCP contains mistakes, omissions, and duplications. This introduces some limitations to this study by necessitating careful data management, often incurring data loss as missing values cannot be accurately imputed. Self-report bias, whilst possible in the trainee-edited details of ISCP, is avoided in the use of ARCP outcomes as a metric, as ARCP panel members prospectively update these. The ISCP did not, at time of writing, collect data on other protected characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, and disability status, and thus, we have not been able to analyse the impact of these factors on trainee progression.

Conclusions

The Covid-19 pandemic had a profound impact on the types of ARCP outcomes received by higher specialty trainees in orthopaedic surgery, with some groups affected more than others. This impact was still seen at the end of 2022, with training trajectory yet to return to its pre-covid pattern. Recovering training and delivering trainees to completion of training to enter the consultant workforce will require time, focus, and resource.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Iain Targett (JCST Data Manager) for his contributions to this manuscript. This study was supported by the Royal College of Surgeons (England) as part of a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Fellowship Award, and logistically by the Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme (ISCP). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organisation. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID19 2020. Available at: www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- Chokshi SN, Efejuku TA, Chen J, Jupiter DC, Somerson JS, Panchbhavi VK. The Effects of COVID-19 on Orthopaedic Surgery Training Programs in the United States. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2023;7(5):e22.00253.

- Bodansky D, Thornton L, Sargazi N, Philpott M, Davies R, Banks J. Impact of COVID-19 on UK orthopaedic training. Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons England. 2021;103:38-42.

- Clements J, Burke J, Hope C, Nally D, Griffiths G, Lund J. SP10.2.6 : The Quantitative Impact of COVID-19 on surgical training in the United Kingdom. Br J Surg. 2021;108(Suppl 7):znab361.187

- Clements JM, Burke JR, Hope C, Nally DM, Doleman B, Giwa L, et al. The quantitative impact of COVID-19 on surgical training in the United Kingdom. BJS Open. 2021;5(3).

- Balvardi S, Alhashemi M, Cipolla J, Lee L, Fiore JF, Feldman LS. The impact of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on the exposure of general surgery trainees to operative procedures. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(9):6712-8.

- Gonzi G, Gwyn R, Rooney K, Boktor J, Roy K, Sciberras NC, et al. The role of orthopaedic trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic and impact on post-graduate orthopaedic education: a four-nation survey of over 100 orthopaedic trainees. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(11):676-82.

- Upadhyaya GK, Jain VK, Iyengar KP, Patralekh MK, Vaish A. Impact of COVID-19 on post-graduate orthopaedic training in Delhi-NCR. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(Suppl 5):S687-S695

- Collins C, Mahuron K, Bongiovanni T, Lancaster E, Sosa J, Wick E. Stress and the Surgical Resident in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of surgical education. 2021;78(2):422-30.

- Shaikh CF, Palmer KE, Paro A, Cloyd J, Ejaz A, Beal EW, et al. Burnout Assessment Among Surgeons and Surgical Trainees During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(5):1206-20.

- Megaloikonomos P, Thaler M, Igoumenou V, Bonanzinga T, Ostojic M, Couto A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on orthopaedic and trauma surgery training in Europe. Int Orthop. 2020;44(9):1611-9.

- Joint Committee on Surgical Training [updated 2022]. Available at: www.jcst.org.

- The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme 2007. Available at: www.iscp.ac.uk.

- The Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh. eLogbook - the Pan-Surgical Electronic Logbook for the United Kingdom & Ireland. Available at: www.elogbook.org.

- Conference of Post Graduate Medical Deans of the UK. A Reference Guide for Postgraduate Foundation and Specialty Training in the UK: The Gold Guide 8th edition 2019.

- Conference of Post Graduate Medical Deans of the UK. Gold Guide 8th Edition; GG8 Derogation COVID Outcomes 10.1 & 10.2. Available at: www.copmed.org.uk/images/docs/gold_guide_8th_edition/GG8_Derogation_-COVID_Outcome_10.1__10.2_.pdf.

- Hope C, Humes D, Griffiths G, Lund J. Personal Characteristics Associated with Progression in Trauma and Orthopaedic Specialty Training: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(1):253-9.

- NHS Digital. Freedom of information Request NIC 581204 https://digital.nhs.uk/about-nhs-digital/contact-us/freedom-of-information/freedom-of-information-disclosure-log/september-2021/freedom-of-information-request-nic-581204-c1p2d 2023 [FOI Request ].

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-9.

- RStudio: Integrated Development for R. 2023.06.2+561. Available at: https://dailies.rstudio.com/version/2023.06.2+561.

- Barter CA, Humes D, Lund J. The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Annual Review of Competency Progression Outcomes Issued to General Surgical Trainees. J Surg Educ. 2024;81(8):1119-32.

- Ahmed M, Hamilton LC. Current challenges for women in orthopaedics. Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(10):893-9.

- Acuña AJ, Sato EH, Jella TK, Samuel LT, Jeong SH, Chen AF, et al. How Long Will It Take to Reach Gender Parity in Orthopaedic Surgery in the United States? An Analysis of the National Provider Identifier Registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479(6):1179-89.

- Hutchison K. Four types of gender bias affecting women surgeons and their cumulative impact. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(4):236-41.

- Hope C, Boyd-Carson H, Phillips H, Griffiths D, Humes D, Lund J. Personal characteristics associated with progression in general surgery training: a longitudinal cohort study. The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2021;103(S1):46-53.

- Ellis R, Brennan PA, Lee AJ, Scrimgeour DS, Cleland J. Differential attainment at MRCS according to gender, ethnicity, age and socioeconomic factors: a retrospective cohort study. J R Soc Med. 2022;115(7):257-72.

- Robinson DBT, Hopkins L, James OP, Brown C, Powell AG, Abdelrahman T, et al. Egalitarianism in surgical training: let equity prevail. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96(1141):650-4.

- Babiker S, Ogunmwonyi I, Georgi MW, Tan L, Haque S, Mullins W, et al. Variation in Experiences and Attainment in Surgery Between Ethnicities of UK Medical Students and Doctors (ATTAIN): Protocol for a Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023;12:e40545.

- Vinnicombe Z, Little M, Super J, Anakwe R. Differential attainment, socioeconomic factors and surgical training. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2022;104(8):577-82.