Pulling up our socks: Improving the management of mechanical thromboprophylaxis in an orthopaedic ward

By Brandon Lim

School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

|

This essay was a runner-up in the 2024 BOA Medical Student Essay Prize Entrants were asked to write a Quality Improvement Project (QIP) on the following topic: 'With the changing demographics and working practices within T&O how can we sustain the work force and standards of care currently provided within the NHS?' |

Background

During my summer elective with the Orthopaedics Department of a teaching hospital in Dublin, I noticed that many patients were not wearing Thrombo-Embolic Deterrent Stockings (TEDS) despite TEDS being indicated in their electronic patient records (EPR). Conversations with the senior house officer and registrars regarding this observation highlighted that this was not a new problem. Although staff were aware of patients not adhering to wearing TEDS, it was difficult for nurses to police the issue. With this knowledge, I hypothesised that an audit on the use of TEDS would probably produce unsatisfactory results. I proposed my plan to conduct this audit to my supervisor and designed an audit tool to aid in data collection. The standard set was that all patients should always wear correctly sized TEDS unless contraindicated, and all patients should be educated on why TEDS were necessary.

The project

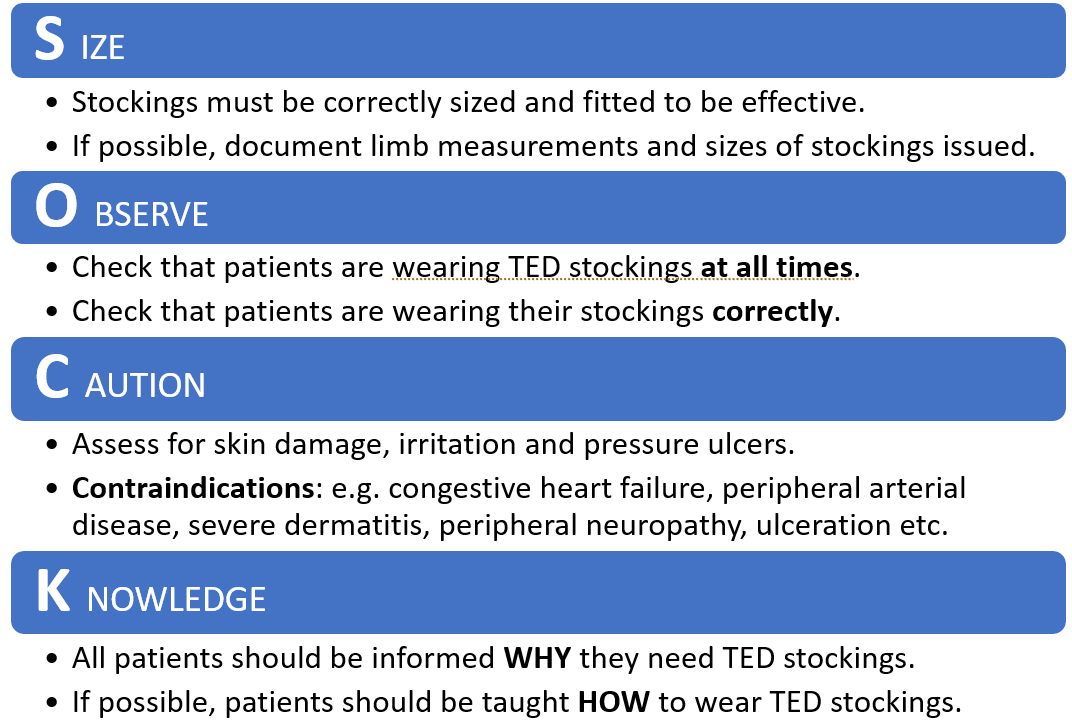

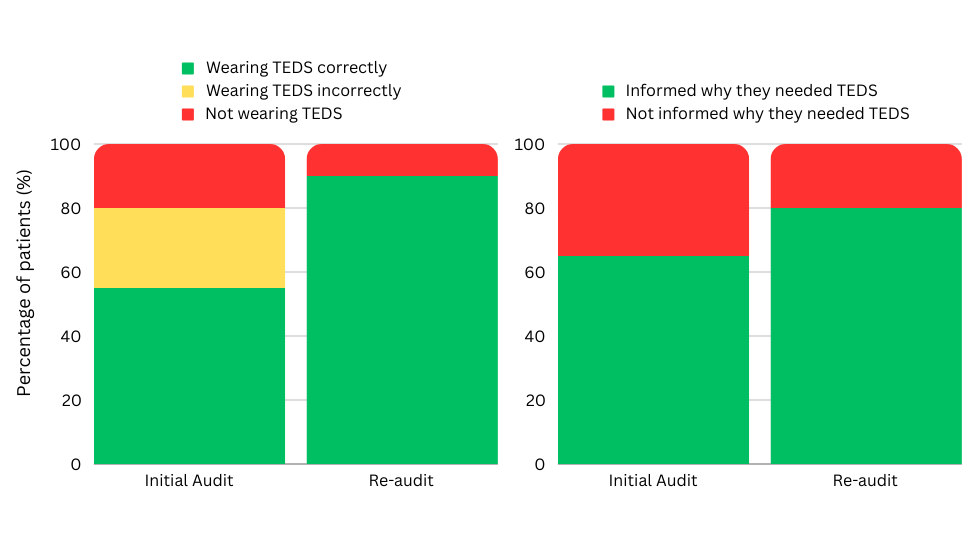

The initial evaluation of 20 orthopaedic patients on the orthopaedic speciality ward found that only 55% of patients were wearing TEDS correctly and only 65% had been told why they needed TEDS. I shared these findings with the nurses and with the aid of an educational poster, I aimed to remind them of the factors to consider when managing patient use and adherence to TEDS. I devised a mnemonic to remind nurses to 1) ensure that TEDS were sized properly; 2) ensure that patients were wearing TEDS correctly at all times; 3) be wary of the side effects and contraindications to TEDS; and 4) educate patients on why they needed TEDS and how to put their TEDS back on if possible (Figure 1). After this educational intervention was implemented, the re-audit demonstrated a significant improvement in adherence and a small improvement in patient knowledge. Among 20 new patients, 90% were wearing TEDS correctly and 80% had been informed by nurses why they needed TEDS. At the end of this QIP, I further recommended that similar audits be regularly conducted to ensure that the standard improves and is maintained. These could be carried out by other medical students as they rotate through surgical placements. I also suggested that information leaflets be designed and given to patients in conjunction with their TEDS to enhance education.

Figure 1: Part of the educational poster (SOCK acronym).

How was this QIP significant?

This QIP was beneficial in two ways. Firstly, it improved the management of the use of TEDS. The educational intervention to remind nurses to be deliberate in checking that patients were wearing TEDS and to inform them of the importance of TEDS when issuing them led to improvements in patient adherence to TEDS and patient understanding of why they needed TEDS (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Results of this QIP.

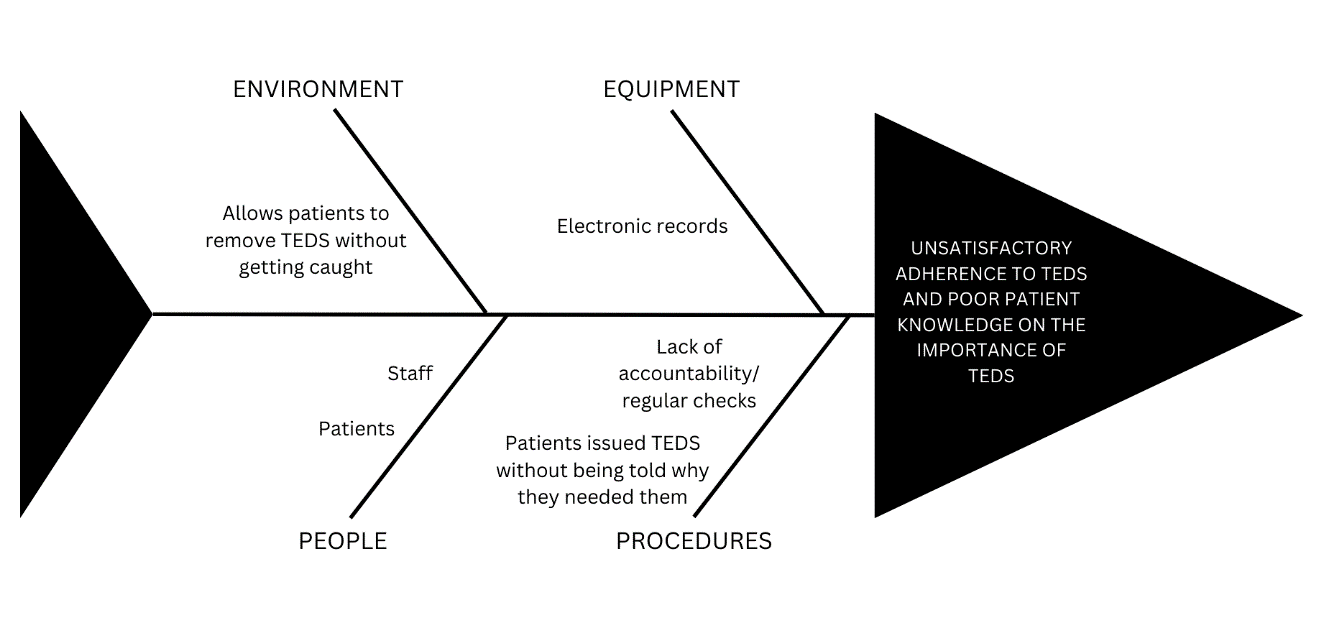

Secondly, identifying the root causes of unsatisfactory patient adherence to the use of TEDS and their poor understanding of the importance of TEDS also revealed previously unidentified issues that needed to be improved. These can be attributed to the following factors: the environment, equipment, people, and procedures (Figure 3). The initial audit found that several patients who were aware that they needed to wear TEDS had hidden their TEDS in drawers or bags or simply thrown them away. These infringements were never detected because patients stayed under their blankets when nurses were at their bedsides. The ward environment thus allowed patients to remove TEDS without getting caught. Nurses also admitted that they did not regularly check whether patients were wearing TEDS. Since not all patients were told why they were given TEDS, some of them were confused as to why they were given these uncomfortable socks and thus refused to wear them. Since adherence to wearing TEDS relied heavily on patients following instructions, it was vital for them to understand why wearing TEDS was important and to not take them off when nobody was watching. Furthermore, nurses blamed their lack of accountability on the EPR, highlighting that there was no dedicated section to account for which nurses had issued the first pair of TEDS and which nurses were subsequently in charge of monitoring patient adherence to TEDS. They were also unaware of hospital guidelines on the use of TEDS or where to find them on the EPR.

Figure 3: An Ishikawa (or fishbone) diagram illustrating the root causes.

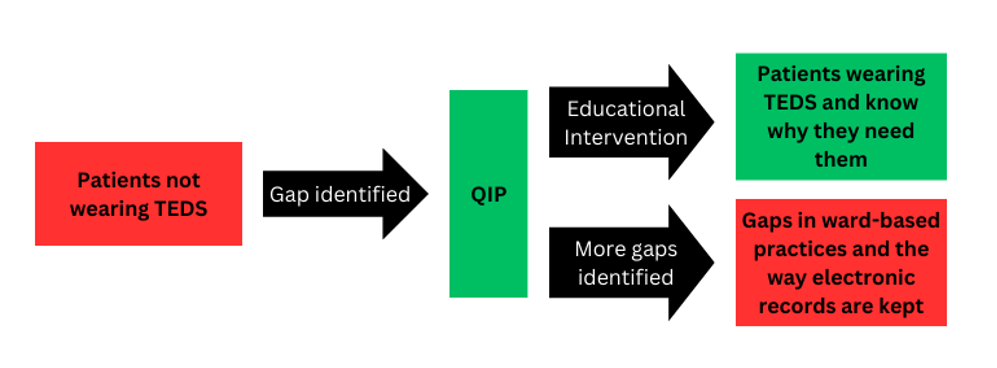

As such, although this QIP was successful in achieving its initial goals, it also incidentally revealed previously unrecognised gaps in patient management (Figure 4). Without the discussions with patients and nurses that took place throughout this QIP, some of these issues may have continued to go unidentified. This QIP highlighted the struggle nurses face regarding accountability with the use of the EPR, and that hospital guidelines regarding TEDS were not easily accessible to them. It also revealed procedural gaps where checking whether patients were wearing TEDS was not on a nurse’s regular list of responsibilities. Now that these gaps have been identified, the department could further improve its practices by tackling these issues in future QIPs.

Figure 4: The QIP process simultaneously improves practices and reveals previously unrecognised gaps.

Conclusion

Undertaking this QIP from its inception to the completion of its second cycle taught me that vigilance and accountability are key to improving the quality of healthcare patients receive and that anyone can implement a positive change. It also equipped me with more confidence and a better understanding of how medical students can contribute to patient care. As healthcare providers, we can never be complacent. The onus is on us to ensure that practices are continuously improved and kept at an optimal level. Although students may see themselves at the bottom of the totem pole within a surgical team, initiating QIPs upon identifying gaps in patient management can still yield significant improvements in practices that might otherwise have been overlooked. QIPs do not need to be complicated, and interventions do not need to be ground-breaking. Student-led QIPs demonstrate that improving practices for the benefit of patients and maintaining standards is the responsibility of all hospital staff, regardless of role and seniority.