Ownership of removed orthopaedic implants

Authors: Devapriyan Johnson, Ahmed Mahmoud, Simon Britten and Samuel Heaton

Ownership of removed orthopaedic implants

Patients occasionally express a desire to retain their removed medical implants. However, there is confusion amongst surgeons and other staff due to lack of clarity regarding ownership, cleaning and packaging of implants before returning them to patients.

Some staff refuse to return orthopaedic implants denying the patient requests, possibly due to infection control concerns. This hesitation is understandable in view of absence of clear guidance. We looked into existing national guidelines and local guidance revealing the complexities surrounding this issue. Additionally, in order to explore the baseline understanding within a group of health professionals regarding retention of removed implants, we carried out prospective questionnaires. We have provided suggestions for adaptions to enable legal compliance and patient satisfaction.

Literature on the possible journey of removed orthopaedic implants

Implant removal is a common orthopaedic procedure1,2. In adults, removal indications include local pain, soft tissue irritation and infection, while in children, the practice also aims to prevent conflicts with the growing skeleton.

Opinions among orthopaedic departments vary, with assumptions that all metal implants are treated as ‘sharps’ and disposed of in a sharps bin, while others even believe that hospital trusts may monetise removed materials through recycling2. If removal is for infection the implant may be sent for microbiological assessment while anecdotally they sometimes become collector items for medical professionals.

In limb reconstruction practice implants are occasionally returned to the manufacturer for investigation if there has been early implant failure. Although returning them seems sensible for biomechanical evaluations and assessments of material properties, these practices are rarely undertaken3. The possibility of sterilising removed implants in low-resource hospitals raises concerns of the potential risks of infections2.

Due to the absence of standards, the handling of removed implants varies based on the discretion of the local healthcare providers. In most hospitals orthopaedic devices are not sent to pathology or returned to the patient but rather disposed of, much like sharps, through local aggregation and eventual incineration.

Figure 1: An 85-year-old lady sustained a periprosthetic fracture of the proximal femur with a broken stem. Before revision hip replacement, she requested to keep her removed implants. Post-operatively, the removed implants were washed and given to the patient in a clear sample bag.

Perspectives within our orthopaedic department

We conducted a questionnaire-based survey within our department. Using opportunistic cohort sampling, we elicited insights from 37 participants, including orthopaedic consultants, junior doctors, theatre staff, ward and clinic nurses. Participants shared their perspectives on the handling of orthopaedic implants post-removal.

When asked about their knowledge regarding what happens to orthopaedic implants after removal, 90% believed they were disposed of, 8% thought they were retained by the health organisation, and 2% suggested they could be given back to the patient. Notably, 57% proposed that patients should not be allowed to keep the removed implants, while 43% were in favour of patients retaining them.

Whilst exploring the ownership of the removed implant, 60% presumed that the health organisation where the implant was applied or removed owns it. 38% believed it belonged to the patient, and the remaining group considered ownership linked specifically to the party who paid for the implant.

Opinions varied regarding the processing of implants before handing them to the patient. 43% advocated sterilisation, 30% preferred decontamination with antiseptic agents, and 27% suggested washing it under a sink would suffice. Overall, the results indicated a prevailing belief that removed implants are disposed of, with a majority presuming that hospitals own these implants. Respondents also revealed a preference for processing implants under sterile conditions before handing them to the patient.

National Regulatory Guidance: Insights from MHRA

The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is an executive agency of the UK Department of Health and Social Care. The MHRA plays a pivotal role in ensuring the effectiveness and safety of medicines and medical devices.

According to advice received from MHRA, guidance on implant ownership stems from Health Notice HN (83)6, issued by the Department of Health and Social Security in 1983. Section 3 of this notice states that upon implantation, an implant becomes the property of the person in whom it has been implanted, retaining this status even if subsequently removed. Section 5 addresses potential disputes regarding the right of health authorities to retain an implant for examination. To navigate such situations, a form of consent has been produced by the MHRA, ideally agreed with the patient and signed before surgery or soon after the implant’s removal when the patient regains consenting capacity4.

The MHRA confirmed that no updates have been made to the guidelines or consent form since 19835. The law regarding consent has shifted over the last 40 years, away from paternalism to a patient autonomy-based model. This favours the concept of returning the implants to patients who requested them, if they are not required for microbiological investigation (infection) or return to the manufacturer for assessment (early or unexpected failure).

Local guidance: Coordinated approach to implant handling

We sought guidance from our hospital’s infection prevention control team and microbiology consultants. They advised a pragmatic approach, suggesting that metal implants could be washed with soap and water before being handed over to patients who wished to take them home. They emphasised clinicians to inform patients that the items were washed and not sterilised.

Further insights were gained through our interaction with the trust-wide surgical safety analyst team. They provided a comprehensive theatre standard policy form specifically designed for instances where patients express a desire to take away removed implants. The form includes patient demographic details, a section completed by medical staff detailing the type of implant, date and time of removal, surgeon and speciality information. Patient consent is a crucial component, acknowledging that the removed implant has been washed but not subjected to any specific decontamination process. The patient also accepts full responsibility for removing the implant from the Trust premises. This local guidance ensures a systematic and transparent approach, balancing patient preferences with infection control measures.

Adaptations to practice

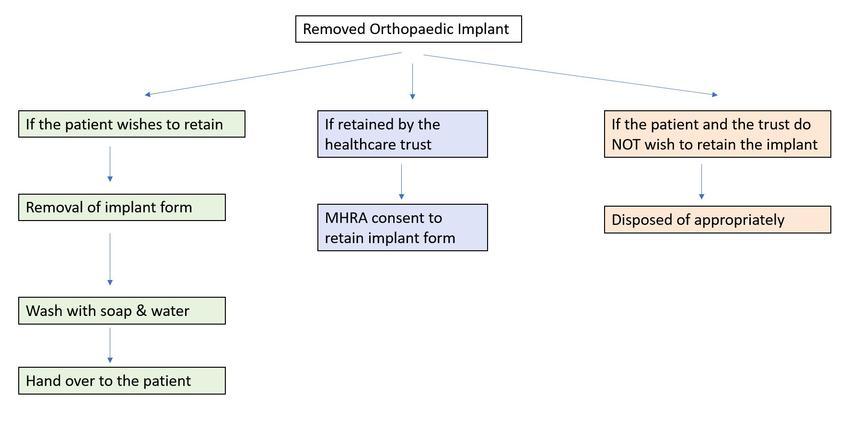

Integrating insights from both the MHRA and our local infection prevention team, we proposed a pragmatic departmental policy for the handling and processing of removed orthopaedic implants. The policy highlights three options based on the preferences: the patient’s desire to receive the implant, the institution’s wishes to retain it for investigation or education, or if neither party wishes to keep the implant.

If a patient wishes to receive the implant, our suggested practice involves completing a form for the removal of the implant. Subsequently, the implant is washed with soap and water and handed over to the patient. The completed document is then kept in the patient’s medical records.

In cases where the institution wishes to retain the removed implant, the proposed practice involves signing the MHRA consent form specifically designed for retaining implants. Conversely, if neither the patient nor the institution wishes to retain the implant, appropriate disposal methods are followed. This adaptive approach ensures a systematic and transparent process in line with both MHRA guidelines and local guidance, balancing patient preferences and clinical needs.

Figure 2: Flowchart demonstrating our recommendations bringing together all the guidelines and infection control advice.

Summary

Foreseeing where the frequency of fracture fixations, joint replacements and subsequent implant removals continues to rise, it is important to navigate the complexities of implant handling post-removal. Our exploration into the perspectives within our orthopaedic department, complemented by insights from national and local bodies, emphasises the need for a standardised approach.

As per current MHRA national guidelines, the implants belong to the patient and should be returned to the patient if they request ownership. The MHRA’s longstanding health notice, untouched since 1983, suggests an opportunity for re-evaluation 40 years on through either the MHRA or a new BOAST (British Orthopaedic Association Standards for Trauma) guideline. We recommend a collective consensus and consideration of new formal guidelines in the handling and processing of removed orthopaedic implants. Meanwhile, explore and adhere to any pre-existing local guidelines in your local hospitals.

The proposed adaptations in practice offer orthopaedic surgeons in our department a framework for managing patient expectations and improving their overall satisfaction. Balancing patient choices, institutional needs, and infection control, this approach not only streamlines implant handling but also advocates patient-centred care.

Key learning points

- Contrary perhaps to popular belief, the patient owns any implanted and then removed surgical implants

- The law and MHRA guidelines governing this go back to the early 1980s, well before any semblance of consent law based on patient autonomy and patient rights

- 40 plus years on, we suggest that the issue should be revisited with the MHRA and the Department of Health and Social Care.

- Individual trusts should have in place guidelines to facilitate safe provision of removed implants to patients if they request them, provided they are not required for microbiological or other analysis in cases of early or unexpected failure.

References

- Böstman O, Pihlajamäki H. Routine implant removal after fracture surgery: a potentially reducible consumer of hospital resources in trauma units. J Trauma. 1996;41(5):846-9.

- Walley KC, Bajraliu M, Gonzalez T, Nazarian A. The Chronicle of a Stainless-Steel Orthopaedic Implant. The Orthopaedic Journal at Harvard Medical School. 2016;17.

- Hothi H, Bergiers S, Henckel J, et al. Analysis of retrieved STRYDE nails. Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(8):599-610.

- Hemming J. Metal-on-metal hip replacements - who owns your implant? Bevan Brittan [website], 2012. Available at: www.bevanbrittan.com/insights/articles/2012/metalonmetalhipreplacements.

- Department of Health and Social Security. Health services management ownership of implants and removal of cardiac pacemakers after death. London: Health Notice HN(83)6, 1983.