Levelling up: How the 'games area' optimises post-operative care in an evolving NHS

Nidhi Vivek

Final year medical student, Brighton and Sussex Medical School

|

This essay was a runner-up in the 2024 BOA Medical Student Essay Prize Entrants were asked to write a Quality Improvement Project (QIP) on the following topic: 'With the changing demographics and working practices within T&O how can we sustain the work force and standards of care currently provided within the NHS?' |

Background

The UK, alongside many other countries, are experiencing the global phenomenon of an ageing population1. This shift in demographics means a larger proportion of the population are aged over 65yr, leaving them vulnerable to medical conditions1,2.

One such condition is osteoporosis – a disease causing weakening of bone structure, making the bones more likely to fracture even after low-energy trauma3. This increase in the active, ageing population coupled with the higher volumes of primary arthroplasty (performed by Trauma and Orthopaedic, T&O, departments nationally), results in a growing proportion of the population at risk of sustaining fragility fractures4,5. The incidence of femoral fragility fractures (FFFs) is projected to rise to 100,000 cases a year from 2033, costing the NHS £3.6-5.6 billion4,5.

FFF pose a significant challenge to healthcare – with the complexity of surgery, the long duration of hospital admission and rehabilitation, and risk of mortality – increasing the burden on healthcare resources2.

Preventative public health strategies are primarily focused on reducing falls and treating patients with osteoporosis at risk of FFFs6,7. Hospital admissions for FFFs provide an opportunity for secondary prevention; however, the administration of bone protective medication is the primary focus7.

Less attention is paid to Hospital-associated Deconditioning (HAD) or post-hospital syndrome - the significant decline following extended hospitalisation, impacting the patient’s physiological, psychological, and functional wellbeing8,9.

Due to long waiting lists for community rehabilitation facilities, patients deemed medically ready for discharge (MRFD) are remaining in hospital for extended periods of time. Recent audits in St Richards and Worthing hospitals reported over 160 MRFD beds every month, putting these patients at increased risk of HAD10. This increases the risk of future falls, adverse outcomes and deteriorating emotional wellbeing – ultimately leading to a reduced quality-of-life (QOL)11-13.

The impact of HAD has consequences on the standard of care delivered and the workforce to support patients with increasing needs. However, its risk could be reduced, using relatively low expenditure methods that develop patients’ mental and physical faculties.

Games area – Service improvement

This quality improvement project (QIP) implemented a ‘Games Area’ (GA) – a service improvement to facilitate re-conditioning for inpatients after surgery. Through using measures that promote higher levels of physical and mental activity, the GA focused on replicating the home environment, so patients can regain their pre-fracture functionality.

The QIP evaluated the effectiveness of GA in preventing HAD for inpatients after surgery for FFF by assessing patient satisfaction and length of hospital stay.

This four-month service improvement was conducted in an orthopaedic ward at Worthing Hospital for patients aged 65yrs or more, who were in rehabilitation after surgery for their FFF, and were deemed fully weight-bearing and MRFD.

The control group received the standard care provided by the ward’s multidisciplinary team (MDT), while the GA group received standard care as well as access to the GA. The GA programme involved patients mobilising to the GA and engage in activities and puzzles with their fellow inpatients, while staying out of their hospital beds.

By ensuring that only patients deemed MRFD were involved in the GA, the service improvement required little monitoring from the ward staff. This ensured that minimal time and efforts were needed to run the GA, so did not add to the workload T&O departments are already under. This also encouraged patients to regain independence with the support of their fellow inpatients, replicating their home environment.

Data were collected from patients via weekly questionnaires and their medical records. To reduce the risk of bias, data for the patients’ satisfaction ratings were collected by hospital volunteers.

Findings

Over the study period, 75 patients participated – with 38 patients in the control group and 37 patients in the GA group.

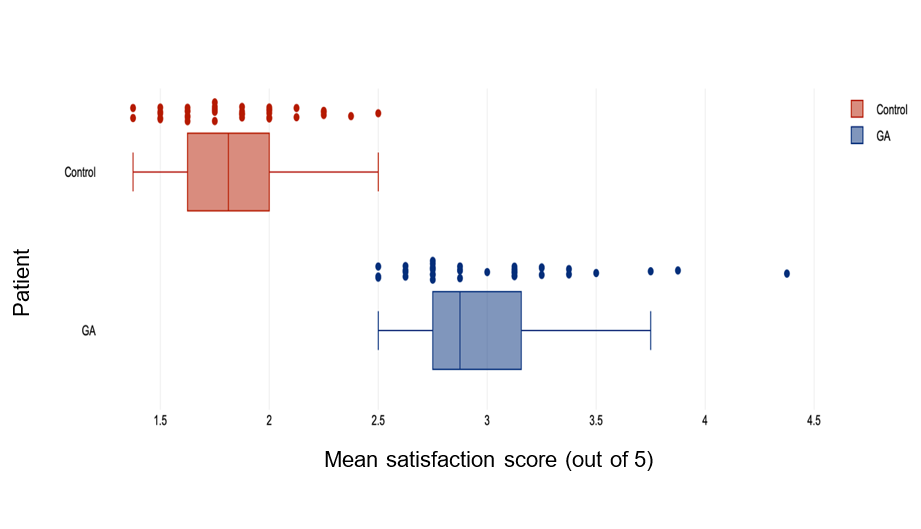

Patients in the GA group reported higher satisfaction ratings (as seen in Figure 1), with a mean score of 3.01 (SD = 0.406) out of 5, compared to the control group’s mean score of 1.83 (SD = 0.279). The median scores for both patient groups were 1.81 for the control and 2.88 for the GA group.

Figure 1: Box plot of patients’ mean satisfaction scores for their hospital stay.

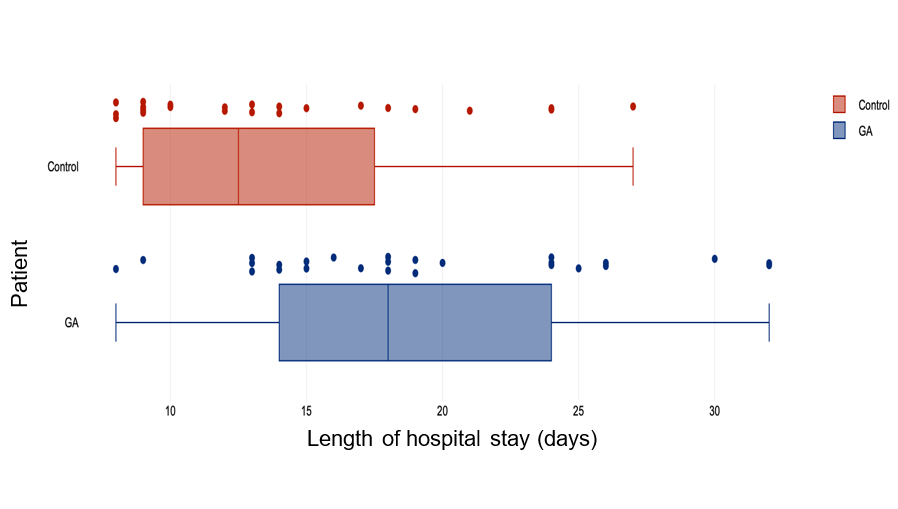

Regarding the length of hospital stay, there was significant variability in the data collected for both patient groups. As seen in Figure 2, the groups showed considerable overlap in terms of the range of length of stay, with large interquartile ranges in both groups.

Figure 2: Box plot of patients’ lengths of hospital stay (from the date of their surgery to their discharge).

Conclusion

The purpose of this QIP was to implement a service improvement (the GA) to facilitate re-conditioning for patients in post-operative rehabilitation for their FFF and assess the effectiveness of the GA in improving patient satisfaction and reducing the length of hospital stay.

Behaviour-change techniques, like the one simulated in the GA, encourage more mental and physical activity for the patients to prevent HAD and thus reduce functional decline13.

The findings of this QIP showed that the GA is an effective service in enhancing the ward environment and so improving patient satisfaction levels. The GA highlighted that even with limited resources and lack of constant supervision, patients can feel more confident in themselves and regain their pre-fracture independence – without adding to the staff’s workload.

However, the GA did not contribute to quicker discharges and shorter lengths of hospital stay for the patients. This may be due to delays in awaiting packages of care or community rehabilitation beds, suggesting the length of hospital stay is dependent on social services rather than hospital-based interventions12.

The future of the NHS entails an increasing and more vulnerable population – and so places greater burdens on the already stretched health and social care services1. With these increasing pressures, applying simple, low-cost interventions (like the GA) are essential for upholding high standards of patient care, while sustaining the work force.

References

1. Mahishale V. Ageing world: Health care challenges. Journal of the Scientific Society. 2015 Sep 1;42(3):138-43.

2. Sànchez-Riera L, Wilson N. Fragility fractures & their impact on older people. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology. 2017 Apr 1;31(2):169-91.

3. Lix LM, Azimaee M, Osman BA, et al. Osteoporosis-related fracture case definitions for population-based administrative data. BMC public health. 2012 Dec;12(1):1-0.

4. Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporosis international. 1997 Sep;7:407-13.

5. Arjan K, Weetman S, Hodgson L. Validation and updating of the Older Person’s Emergency Risk Assessment (OPERA) score to predict outcomes for hip fracture patients. HIP International. 2023 Feb 14:11207000231154879.

6. NHS England. Recondition the Nation. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/blog/recondition-the-nation. [Date accessed: 28/10/2023].

7. Smith TO, Sreekanta A, Walkeden S, Penhale B, Hanson S. Service improvements for reducing hospital-associated deconditioning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Gerontology and geriatrics. 2020 Sep 1;90:104176.

8. Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Factors associated with recovery of prehospital function among older persons admitted to a nursing home with disability after an acute hospitalization. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009 Dec 1;64(12):1296-303.

9. Hawley S, Inman D, Gregson CL, Whitehouse M, Johansen A, Judge A. Predictors of returning home after hip fracture: a prospective cohort study using the UK National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD). Age and Ageing. 2022 Aug;51(8):afac131.

10. Goubar A, Ayis S, Beaupre L, et al. The impact of the frequency, duration and type of physiotherapy on discharge after hip fracture surgery: a secondary analysis of UK national linked audit data. Osteoporosis International. 2022 Apr 1:1-2.

11. Patel R, Judge A, Johansen A, et al. Multiple hospital organisational factors are associated with adverse patient outcomes post-hip fracture in England and Wales: the REDUCE record-linkage cohort study. Age and Ageing. 2022 Aug;51(8):afac183.

12. Sheehan KJ, Goubar A, Martin FC, Potter C, Jones GD, Sackley C, Ayis S. Discharge after hip fracture surgery in relation to mobilisation timing by patient characteristics: linked secondary analysis of the UK National Hip Fracture Database. BMC geriatrics. 2021 Dec 15;21(1):694.

13. Lee SY, Beom J, Kim BR, Lim SK, Lim JY, Fragility Fracture Rehabilitation Study Group. Comparative effectiveness of fragility fracture integrated rehabilitation management for elderly individuals after hip fracture surgery: A study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Medicine. 2018 May 1;97(20):e10763.