Inequality, discrimination and regulatory failure in surgical training during pregnancy

By Sara Dormana, James Sheltona and Danielle Whartonb

aOrthopaedic Speciality Registrar, Health Education North West (Mersey Sector)

bConsultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Whiston Hospital, Prescot, UK

Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Published 01 September 2020

Introduction

In recent years there has been increasing literature reporting difficulties experienced by women working in surgical specialities. Some publications have named Trauma and Orthopaedics (T&O) as the most 'sexist' specialty1 with others highlighting gender discrepancy of women in leadership roles2. Lack of flexibility towards part-time careers, gender stereotypes and poor work-life balance are commonly suggested as some of the main barriers for female surgeons.

The World Health Organization has recently published a gender equality analysis report entitled 'delivered by women, led by men'. The reports highlights that despite women accounting for 70% of the health and social care workforce worldwide, female health care workers face barriers at work not faced by their male colleagues. This may lead to them undermining of their own well-being and livelihoods, constraining further progress on gender equality and negatively impacting health systems and the delivery of quality care3.

In the UK, female surgical trainees commonly report dissatisfaction with lack of support and available guidance during pregnancy and maternity leave. Training in T&O whilst pregnant can be particularly challenging due the unique risk profile associated with the specialty and the many potential hazards to both mother and child4, including ionising radiation5,6 and exposure to teratogenic chemicals7,8. Some professional bodies have made steps towards improving guidance9-15, however, the information is difficult to access, fragmented and not specific to T&O. Moreover, there is a lack of awareness amongst trainees and trainers of the resources that are currently available.

Anecdotally, guidance and risk assessment currently available for pregnant trainees is perceived as a 'tick box' exercise rather than providing useful, practical or safe advice.

While some may argue that a pregnant T&O trainee is a rare occurrence, it is important to consider the changing trends in the workforce population. In the UK, 55% of current medical students and 59% of doctors in training are female. Whilst surgical specialties have traditionally been a male dominated field, the number of female trainees continues to rise and currently one in three surgical trainees are female16.

It is therefore likely that managing pregnant surgical trainees will become increasingly commonplace in the future. Should surgical specialties wish to continue attract highly-skilled, competitive female trainees, these issues need to be addressed.

Aims

The primary outcome of this study was to identify whether employers are meeting the statutory requirements for safe working conditions of pregnant trainees in T&O training posts. Secondary outcomes were to explore common difficulties encountered by trainees and trainers, highlight areas of both negative and positive practice and to identify any cross speciality differences in practice between T&O and a control group of obstetric and gynaecology trainees.

It is anticipated that this study will raise awareness of common issues, promote positive culture change and form the basis of specialty-specific guidance for management of pregnant trainees in T&O surgery.

Methods

Two separate questionnaires (Trainee and Trainer) were created using an electronic form.

Trainer Questionnaire: All T&O Training Program Directors (TPD) and Academic Educational Supervisors (AES) were invited to complete the Trainer questionnaire. Direct experience of managing a trainee during pregnancy or maternity leave was not required. Trainers were contacted through local regional networks, the T&O TPD forum and through social media advertising. The trainer questionnaire recorded basic demographic information including role and region of work, knowledge of risk assessment, specific guidelines, advice provided on risk exposure and perceptions of support for trainers managing trainees during pregnancy, maternity leave and returning to work.

Trainee Questionnaire: All trainees with a national training number (NTN) in either T&O or Obstetrics and Gynecology (control group) who had taken a period of maternity leave in the last five years were invited to complete the trainee questionnaire.

The trainee questionnaire was distributed through the British Orthopaedic Trainees Association (BOTA) regional Representative’s network, Women in Surgery network, deanery administration and through social media advertising. The questionnaire recorded basic demographic information including stage and region of training, risk assessment, specific risk exposure and perceptions of support during pregnancy, maternity leave and returning to work. Combination of closed and open questions were utilised. Open question responses were analysed using qualitative research methods17.

Results

A total of 90 trainees and trainers participated in the study.

Trainer Questionnaire

A total of 22 T&O Trainers across nine deaneries participated.

Awareness of existing guidance for management of pregnant trainees was low. Only 36% of T&O trainers were aware of local guidance, regional guidance (50%) and national guidance (22%). Only 27% of trainers felt adequately prepared by their department to support a pregnant trainee.

Regarding the management of a pregnant trainee; 46% of trainers had direct experience. When asked about advice provided on specific risk factors, 45% did not know who was responsible for performing an occupational risk assessment of a pregnant trainee. In the majority of cases either no advice was provided or trainees were advised to avoid the 'at risk' activity completely with a significant impact on subsequent training opportunities (Table 1).

|

Advice Given |

Radiation |

Cement |

Iodine |

|

No guidance offered |

50% |

77% |

82% |

|

Avoid Completely |

36% |

23% |

18% |

|

Direct to existing guidance |

14% |

0% |

0% |

Trainer thematic analysis

Two common themes were (1) lack of specialty specific guidance and (2) impact on training and department resources. Trainers commonly highlighted the need for improved engagement from both trainees and trainers, logistical difficulty with placements, need for increased awareness and clearer guidance to help facilitate a 'training contract' to establish reasonable expectations. These themes are supported by in vivo examples.

|

Theme |

Example |

|

Guidance |

“There is a paucity of clear guidelines, much of what we do is based on hearsay.” “Clearer guidelines on acceptable work activity would allow a more uniform approach and therefore a more standardised accommodation of training needs.” “I felt able to provide support in terms of workload and providing general consideration but I was unaware of the issue of cement or iodine containing preparations - our hospital policy makes no mention of this. Specific guidance would be helpful in order for us to provide a safer environment.” “It’s a wonderful thing expecting a child and happy to go with what this highly motivated group want. They are knowledgeable and will know when it is safe to work and when not. Little interference needed.” |

|

Training and Resources |

“It is a belief that the pregnant trainees can pick and choose lists without imaging / cement and boot out other trainees who are on that firm, so they can get the operating experience. I will not allow that to happen - as it is discriminating against the male trainees.” “Some trainees have refused to do anything related to imaging. It’s their decision and we will adapt to what they want within reason. I will not compromise the training of male trainees because another trainee is pregnant.” “Perhaps an extension to training is required – but done without being punitive. When theatre is avoided it is the practical/craft skill development that suffers.” |

Orthopaedic Trainees

45 trainees (68 pregnancies) across 25 UK training programmes spanning all four countries within the UK were recruited. For the same time period Joint Committee for Surgical Training (JCST) reported 81 episodes of Out of Programme (OOP) for maternity leave resulting in an 84% response rate. The majority of pregnancy and maternity leave were taken during the middle of training (ST4/5).

Risk exposure

62% of trainees received no formal advice on risk exposure during pregnancy. Of those who did receive advice only 22% (four women) felt it was adequate. 93% felt the need to independently research and decide what was 'safe' due to lack of guidance. Almost all trainees had continued risk exposure; 91% continued to use cement and 96% continued to use radiation. Only 18% were offered a radiation monitor, a further 27% received a monitor through self-directed measures and less than 5% received feedback as to whether radiation exposure remained within safe fetal limits.

Most trainees undertook self-directed measures to reduce risk including wearing double lead gowns (64%), standing >2m away from image intensifier during use (47%), and avoiding surgical cases requiring the use of radiation (42%). A third of women took no additional precautions.

Training

75% of trainees felt there was significant compromise in training during pregnancy. Common problems included tiredness and high workload intensity (55%), illness including nausea and vomiting (34%), inappropriate high risk cases out of hours, (25%) and difficulty completing on calls (59%). 69% chose to stop on call commitments prior to maternity leave.

There was a lack of engagement with Keeping in Touch (KIT) days with 50% of trainees using no KIT days at all.

One in five women reported that they felt their maternity leave was too short. Common reasons for returning to work early were trying to fit in around placement changeover (35%), concerns about surgical de-skilling (28%), financial pressure (13%) and pressure from their employer (3%).

51% returned to work on a less than full time basis and 68% felt well supported in returning to work. 17% were offered a phased return to on calls. On returning to work, more than 50% trainees reported that it took six months or more to regain their pre-pregnancy level of confidence and technical skill. One in four felt they were treated differently by colleagues and trainers on returning to work.

T&O trainee thematic analysis

There was an overarching theme that participants felt a lack of practical guidance was at the core of many of the issues. Both trainees and trainers appeared to make efforts to adapt and accommodate to the situation were possible. Underlying issues included, conflicting personal and career decisions, under-representation, rigidity in surgical career structures and logistical aspects of training, bullying and discrimination in current surgical practice and non-compliance with statutory requirements such as lack of risk assessment or completion by inappropriate staff.

Positive themes

The participants felt in most cases trainers and colleagues were generally supportive but lack of information and understanding led to many of the resultant negative themes.

Negative themes

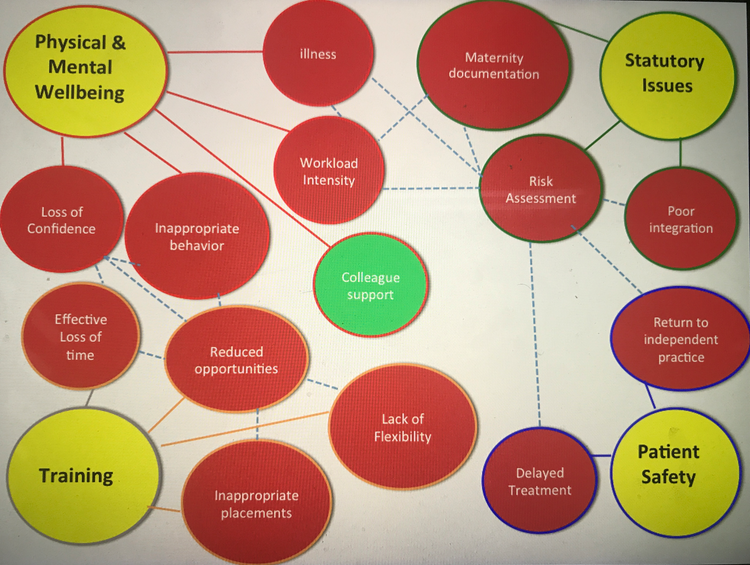

Common difficulties encountered broadly covered four main domains (1) physical and mental wellbeing (2) statutory issues (3) patient safety and (4) training. These themes are supported by in vivo quotes from the data.

A diagrammatic representation of common themes is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1

|

Theme |

Example |

|

Physical and Mental Wellbeing |

“ A key trainer told me I should raise my children at home.” “ I felt my trainers had shifted me out of the surgical colleague box and into a category with their wives.” “ Everyone felt I was overreacting when I said I didn't feel confident to operate anymore.” “Working in an all male department and expressing breastmilk can be difficult. As a result I had to express in my car, shower cubicle, toilet, changing rooms etc. by trying to find a spare 15 minutes instead of eating lunch.” |

|

Patient Safety |

“A frail patient lay asleep on the table for 45minutes while a radiographer called my consultant at home for permission to proceed – as a grown adult it was my body and my decision.” “Within an hour of returning to work I was operating alone – against my wishes.” |

|

Statutory Issues |

“I felt like the first person in the history of the NHS to be pregnant.” “ It was like the blind leading the blind.” “My rota coordinator emailed all the other registrars, not only announcing my pregnancy but also quoting my sick note detailing I was unable to cope when asking them to cover.” “The pregnancy work assessment was done by a medical staffing secretary who had no clue about the occupational risks/exposure.” “ Occupational health were of no help and even questioned why I was seeing them to report my pregnancy.” “I had to seek the information myself but no one including the national radiation adviser was able to give me a definitive answer to what’s safe and what’s not.” |

|

Training |

“My rotation wanted to send me to our major trauma center for 7 weeks, between week 30 and 38 of pregnancy. When I objected, for both practical and pay reasons, both were rejected and I was forced to trigger my maternity leave early at 30 weeks.” “It takes a long time to build confidence back up and this is made more challenging with multiple maternity leaves leading to staccato training.” “Trainers and TPD had no idea about risks and had no useful advice other than just go off early if I felt I couldn’t do the jobs.” “Left the on call rota when rotating posts at 28 weeks (with 8 weeks left to work) to avoid heavy night shifts at an MTC. Despite adequate notice and a relevant letter from my midwife and fit note from my GP this was criticised by senior consultants.” “I was dismissed from theatre by supervisor as he didn’t want my morning sickness to infect his joint replacement.” “Lack of understanding/empathy especially at ARCP. Bullying and harassment associated with requiring adjustments.” “Trainers assume you are not ambitious/want to work part time/don’t need to be trained very much.” |

Control Group (O&G)

A control group of O&G registrars were recruited. In total 23 registrars (38 pregnancies) completed the trainee questionnaire. Results were comparable with the T&O trainees.

Only 35% were aware of existing guidance for the management of pregnant trainees and only 35% received formal risk assessment or advice during pregnancy. Less than half felt that any advice received was adequate and 87% felt it was left to them to decide what was safe practice. Only 17% used radiation during pregnancy and 4% received a radiation monitor. 69% needed to discontinue on call commitments before commencing maternity leave. During maternity leave 52% used no KIT days. 61% felt well supported on RTW and 35% were offered a phased return. One in four felt it took greater than six months to return to their pre-pregnancy level of skill and decision-making.

Thematic analysis demonstrated the same four broad domain and sub-analysis with no additional themes detected.

Discussion

Many of the highlighted issues stem from an overarching theme of an inflexible training infrastructure, lack of communication and clear guidance on what is reasonably expected from the employer, trainer and trainee. Occupational health departments are currently responsibility for providing advice for hospital workers regardless of speciality or job title. Although T&O has specific additional risk factors that need to be addressed we believe this is an issue affecting workers of all backgrounds and specialities in the UK hospital setting. Furthermore recent international publications have highlighted gender inequalities, discrimination and undermining of women with the need for culture change in surgical specialities.

Statutory Requirements

There is a need for a significant improvement in the channels of communication between local hospitals, training programmes and employing health education boards. Given the complex nature of the 'employing body' for rotating doctors, trainees commonly report a 'passing the buck' phenomenon where it is unclear who is ultimately responsible for the safety and welfare of the trainee. As a result trainees are often passed from pillar to post with a lack of clear or practical guidance and ultimately end up being told to avoid any risk they ‘do not feel comfortable with’. Given the significant risk exposure in T&O training posts in addition to evidence that rates of miscarriage and adverse outcome are higher in residency and with night work18,19, it is concerning that most trainees had no risk assessment undertaken. In cases where a risk assessment was performed, it was frequently conducted by inexperienced or non-clinical personnel, which is neither appropriate, safe nor reasonable in modern practice.

Perhaps most concerning is the complete failure of many trainers to abide by UK anti-discrimination law to prevent disadvantage during pregnancy. There is evidence of clear discrimination within surgical training posts. The equality act states that discrimination in the form of 'unfavourable treatment' of a pregnant women in the workplace includes (1) unfair treatment, (2) suffering disadvantage due to pregnancy or maternity through her employer’s policies, procedures, rules or practices or (3) suffering unwanted behaviour20. Specific in vivo examples and ACAS discrimination definitions are provided in Table 4. The most frequent areas of conflict are due to training, absence, work performance and returning to work discrimination.

|

Type of Discrimination |

Definition |

In vivo example |

|

Training |

Missing out on training opportunities due to pregnancy, maternity leave or obstetric related illness |

“I was dismissed from theatre by supervisor as he didn’t want my morning sickness to infect his joint replacement.” |

|

Absence |

Negative comments or warnings about absences |

“Left the on call rota at 28 weeks to avoid heavy night shifts at an MTC. Despite adequate notice and a relevant letter from my midwife and fit note from my GP this was criticised by senior consultants.” “Told by TPD not to have another child in training.” |

|

Work Performance |

The employer will need to be understanding, and if necessary make allowances, if an employee’s work performance dips at times because of her pregnancy or a pregnancy-related illness. Such changes agreed between employer and employee would have to be taken into consideration fairly in her appraisal, assessment or review - her performance must not be marked down because of pregnancy and maternity reasons |

“Expectation to carry on despite major pregnancy complications. Lack of understanding/ empathy especially at ARCP. Bullying and harassment associated with requiring adjustments.”

|

|

Returning to work (RTW) |

Pressure to return to work early |

“ Told by TPD had to return for changeover date.” |

Significant problems also exist for breastfeeding mothers returning to work. UK law states that employers must provide a suitable area of rest for breastfeeding mothers for one year after childbirth. Specifically, it comments that use of toilets are not deemed to suitable locations; a commonly reported location many trainees were forced to use on returning to work and usually at the expense of natural working breaks 20.

Our findings confirm there the lack of adherence to statutory requirements, which may be a ticking time bomb for medicolegal matters and should be addressed urgently. It is essential that moves be made to improve pregnancy and maternity awareness and training for staff in relevant positions.

Impact on training

Another major issue facing both trainees and trainers particularly in craft specialities is the negative impact and cost of 'effective training' time. The majority of trainees reported significant compromise in training during their nine months of pregnancy due to either self or enforced avoidance of operating, reduced on call experience and illness. This is confounded by lack of clinical contact during maternity leave and poor engagement with KIT days, with most trainees reporting it took a minimum of six months to return to their pre-pregnancy level of skill.

KIT days are an invaluable resource for maintenance of confidence and practical skill. It is also beneficial in helping trainees in adjusting to RTW, and think about practical aspects of managing a work-life balance and organisation of childcare. Several perceived barriers to taking KIT days raised, were due to lack of 'trainee ownership'. Trainees felt they were no longer part of a 'firm or department' whilst on maternity leave and felt there was no easy point of contact in which to arrange and take clinical KIT days. An early decision about the location of the RTW placement, with an allocated educational supervisor or mentor whilst on maternity leave would provide a clear contact and consistent supervision both helping to maintain skills whilst on maternity leave and support RTW.

Significant improvements need to be made to mitigate the compromises in training currently being experienced. A single pregnancy has demonstrated trainees can expect up to 15 months of compromised training and most trainees had more than one pregnancy during the six years of higher surgical training leading to a 'staccato' training effect. A number of trainees reported successful completion of ARCP but would have welcomed the option of voluntary additional training time for this reason. This issue has already been addressed and is now offered in the new RTT programme.

Due to the negative impact on training it is recommended that both individual trainees and regional training programs consider potential strategies to minimise the impact of a pregnancy earlier in higher surgical training. It is reasonable to provide advice to trainees at the beginning of their training regarding planning and consideration should be given to providing practical advice at training program inductions (were possible) in advance about timing of children and its impact on careers, FRCS, fellowship, geographical location/ commutes and placement choices. The most common time to take maternity leave was in the middle of training it is therefore sensible to consider that thought should be given to permitting female trainees to undertake the more arduous or geographically difficult placements earlier in training and should be individualised depending on the trainees intentions.

It is also recommended that trainees inform their training programme director as early as possible regarding their pregnancy in an effort to mitigate the logistical difficulties associated with training/placement adjustments and the knock on effect on other trainees and departments. Whilst we agree that training adjustments should not compromise the training needs of other trainees, the majority of training programmes have ample capacity to accommodate a pregnant training in a post that would not discriminate against the needs of others.

Specialty-specific guidance

Whilst there are a number of existing guidelines regarding the management of the pregnant trainee, these are fragmented, vague and lack key practical information. We believe that the introduction of comprehensive orthopaedic specialty-specific guidance in a single document would be welcomed by both trainees and trainers. We recommend that ‘Practical Guidance for Orthopaedic Trainees during Pregnancy’ should cover (1) Maternity documentation and statutory requirement (2) risk assessment & exposure (3) dealing with on calls & placements (including reasonable expectations) and (4) returning to work. A suggested draft framework has been included in Appendix 1. We envisage this forming a framework to challenge existing behaviors, promote positive culture change allowing trainees and trainers to establish a personalised ‘training contract’, through open dialogue, which would allow both parties to overcome the issues described above. Ideally this should be reviewed and agreed by the important stakeholder groups and relevant governing bodies.

Limitations

It could be argued that in a voluntary questionnaire bias is introduced, as trainees with negative experiences are more likely to respond. However despite this, the authors believe that a sample of 45 female orthopaedic trainees with 68 pregnancies and representation from 25 of the 31 training programmes within the UK is an acceptable sample. In an effort to quantify the true number, ISCP were contacted for information on how many female orthopaedic trainees had taken an episode of OOP for maternity leave in the last five years. ISCP confirmed via email communication that a total of 81 episodes for this time period had been registered, suggesting an 84% capture rate. (e-mail to Sara Dorman from Paul McCabe JCST Data Manager, Jan 16, 2020; unreferenced).

Similarly one could consider that engaged trainers are more likely to complete the trainer questionnaire and that the true awareness may be lower than reported. Despite a series of personalised email requests and discussion at the TPD forum, there was a lack of trainer engagement with only 9 of 31 T&O training programme directors responding; suggesting that the issue is not a primary concern even for key trainers.

Conclusion

There is currently wide variation in management of pregnant T&O trainees with many women reporting negative experiences during pregnancy and when returning to work after a period of maternity leave. Occupational risk assessment is a basic statutory employer responsibility that is not currently adequate. There are issues to be addressed with regards to practical aspects of job planning, workplace bias, effective loss of training time towards CCT, lack of engagement with KIT days and lack of awareness of guidance from key trainers. It is expected that T&O specialty specific guidance would provide both Trainers and Trainees with current and consistent ‘user friendly’ recommendations.

Although this review has focused on issues experienced by T&O trainees during pregnancy, the occupational health departments in question are responsible for assessing all hospital workers in the UK. It is therefore possible that these issues may be affecting hospital workers from any background or subspecialty. Further cross speciality and international research is warranted.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to colleagues from the Mersey Deanery including Mr James Shelton, Mr Edward Wood, Mr Cronin Kerin, Ms Alison Waghorn, UK head of school for surgery, members of the Mersey Specialty Training Education Committee, British Orthopaedic Trainee Association and Ms Kath Hamlin for their input and advice.

References

- Bellini MI, Graham Y, Hayes C, Zakeri R, Parks R, Papalois V. A woman's place isin theatre: women's perceptions and experiences of working in surgery from the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland women in surgery working group. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e024349.

- Skinner H, Burke JR, Young AL, Adair RA, Smith AM. Gender representation in leadership roles in UK surgical societies. Int J Surg. 2019;67:32-36.

- World Health Organisation. Delivered by women, led by men. Delivered by Women, Led by Men: A Gender and Equity Analysis of the Global Health and Social Workforce. Human Resources for Health Observer [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Feb 10]; Available at: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/health-observer24/en/.

- Downes J, Bauk PN. Vanheest, AE. Occupational hazards for pregnant or lactating women in the orthopaedic operating room. J Am Acad Ortho Surg. 2014;22(5):326-32.

- Keene RR, Hillard-Sembell DC, Robinson BS, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ. Occupational hazards to the pregnant orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone J Surg Am. 2011;93(23):1411-5.

- Uzoigwe CE, Middleton RG. Occupational radiation exposure and pregnancy in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:(1)23-7.

- National Institute Clinical Excellence. British National Formulary. Povodine-Iodine [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 23]. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/povidone-iodine.html.

- Ecolab. Videne. Povodine-Iodine 7.5% w/w surgical scrub. Manufacturer Guidance [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 23]. Available at: https://www.hpra.ie/img/uploaded/swedocuments/459764a3-cd39-4a94-af57-7314232a2915.pdf.

- Joint Committee on Surgical Training. Guidance on the management of surgical trainees returning to clinical training after extended leave [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 20]. Available at: https://www.jcst.org/-/media/files/jcst/key-documents/return-to-work-guidance-final.pdf.

- Royal college of Surgeons Edinburgh. Pregnancy and Surgery. Working in Surgery While Pregnant [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 10] . Available at: https://www.rcsed.ac.uk/professional-support-development-resources/career-support/return-to-work/pregnancy-and-surgery.

- Royal College of Surgeons England. Surgery, Pregnancy and Parenthood [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Feb 10]. Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/women-in-surgery/parenthood-with-a-surgical-career.

- NHS Plus, Royal College of Physicians, Faculty of Occupational Medicine. Physical and shift work in pregnancy: occupational aspects of management. A national guideline. London: RCP [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Mar 23]. Available at: https://www.nhshealthatwork.co.uk/images/library/files/Clinical%20excellence/Pregnancy-FullGuidelines.pdf.

- NHS Employers. General Maternity Guidance for rotational Junior Doctors in Training [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 May 20]. Available at: https://www.nhsemployers.org/~/media/Employers/Documents/SiteCollectionDocuments/Maternity%20Factsheet.pdf.

- British Institute of Radiology, The Royal College of Radiologists. The College of Radiographers. Pregnancy and Work in Diagnostic Imaging Departments 2nd Edition [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Mar 23]. Available at: https://www.rcr.ac.uk/publication/pregnancy-and-work-diagnostic-imaging-departments-second-edition.

- Health and Safety Executive. Working safely with ionising radiation: Guidance for expectant and breastfeeding mothers [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 May 20]. Available at: http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg334.pdf.

- General Medical Council. Our data on medical students and doctors in training n the UK [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Feb 10]. Available at: https://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/SoMEP_2017_chapter_2.pdf.

- Braun V, Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych 2006;3(2):77-101.

- Begtrup LM, Specht IO, Hammer PEC, Flachs EM, Garde AH, Hansen J, et al. Night work and miscarriage: a Danish nationwide register-based cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(5):302-8.

- Behbehani S, Tulandi T. Obstetrical complications in pregnant medical and surgical residents. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(1):25-31.

- Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service. Pregnancy and maternity discrimination: key points for the workplace [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Feb 10]. Available at: https://www.acas.org.uk/media/4945/Pregnancy-and-maternity-discrimination-key-points-for-the-workplace/pdf/Pregnancy___Maternity_Discrimination.pdf.