Gender balance in medico-legal reporting

Authors: Jo Round, Sarah Johnson-Lynn, Charlotte Lewis, Jacquelyn McMillan, Jan McCall, David Warwick, Deborah Eastwood and Simon Britten

Gender balance in medico-legal reporting

The British Orthopaedic Association is committed to promoting diversity and inclusivity throughout Orthopaedics. Priority 1 of the 2020-2022 Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan1, is to understand and define groups that are currently under-represented across the BOA.

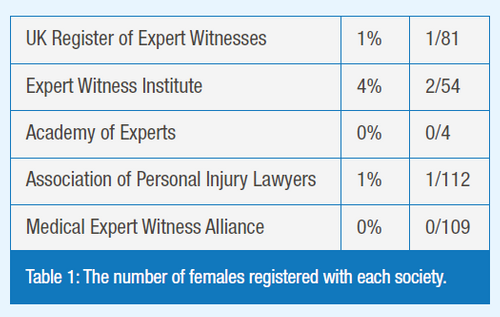

As part of the Medico-Legal Committee’s commitment to this, we investigated gender balance amongst UK experts involved in medico-legal reporting in T&O. 8% of home members within the BOA are female, yet only 1% of medico-legal experts appearing on the current registers in T&O, are female (Table 1).

The aim was to investigate the apparent gender imbalance in medico-legal reporting and identify we could do to address it. We sent out a survey to all BOA members, asking them to complete it, whether or not they had any medico-legal experience.

The results

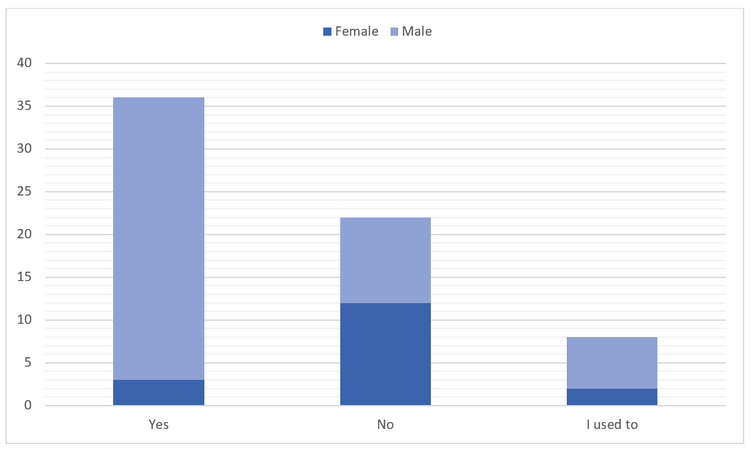

68 people responded to our survey; 49 were male and 18 female. One respondent preferred not to say their gender, unfortunately their responses could not be analysed due to sample size.

8% of our respondents who do medico-legal work are women (Figure 1), in keeping with the gender balance amongst the BOA’s home fellows. Although there were only three female respondents to this question. Nevertheless some interesting insights can be seen.

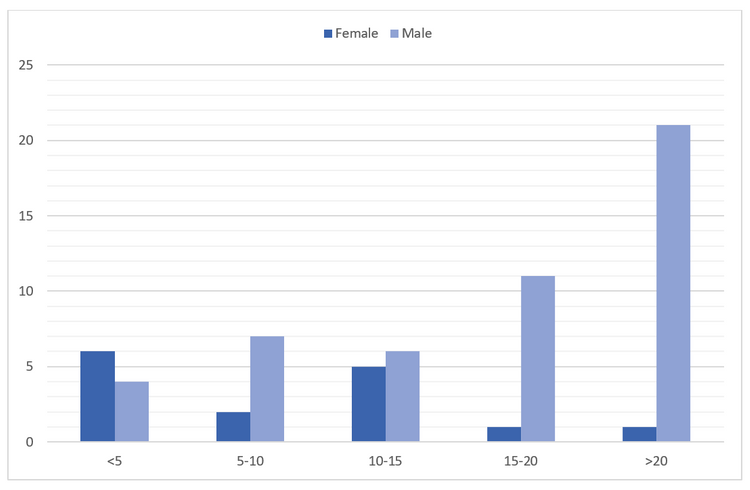

Time in post

Guidelines from the Royal College of Surgeons state, “It is unlikely that anyone would be called as an expert witness within the first five years of practice”2. Therefore we looked at how long our respondents had been in post. 40% of women surveyed had been in post less than five years. This compares with 8% of men, (Figure 2). Discussion with senior authors confirmed that while at least five years experience is probably necessary for negligence work, it is reasonable to be practising in Personal Injury reporting sooner than that. This unfounded perception by younger Consultants may be the reason some have not entered medico-legal work.

Private practice

Only 27% of the women surveyed, are doing private practice. This smaller number may again relate to their experience and represent a time lag. So it does not seem as if women are doing private practice instead of medico-legal work.

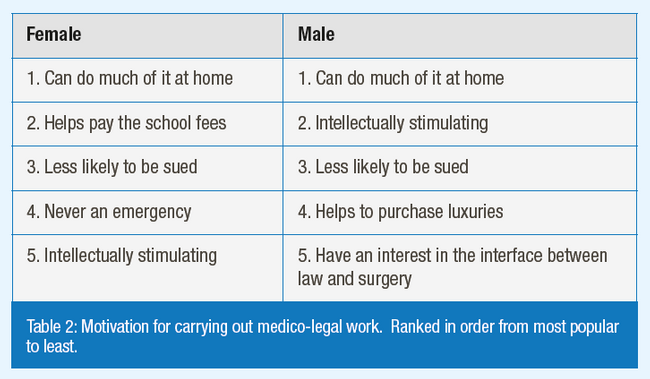

Motivation for medico-legal work

We asked people who did medico-legal work what motivated them to do it. We then ranked reasons for each gender, as shown in Table 2. There was a lot of commonality between the genders. The top ranked reason for both was the fact that much of it could be done from home.

Of equal ranking in both lists was the fact that they felt medico-legal work gave them insight into their own practice and makes them less likely to have a claim submitted against them. Intellectual stimulation also appeared on both lists. Although the extra income comes in useful for both genders it seems women prefer to pay the school fees and men prefer to buy luxuries. There were some differences noted, however. Women liked the fact that there is never an emergency whereas men seemed more likely to have an interest in the interface between law and surgery.

Deterrents to medico-legal work

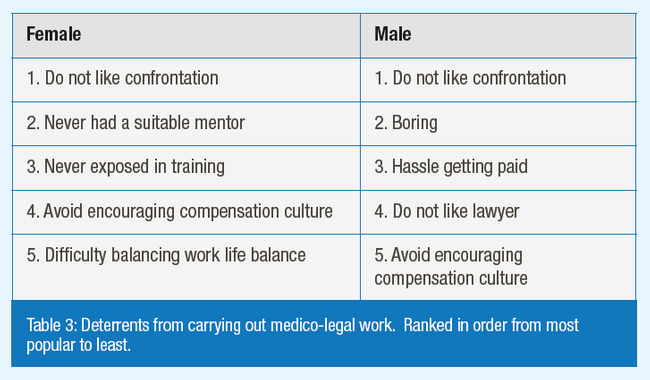

There was more of a difference in the reasons why people do not go into medico-legal work, between the genders, as shown in Table 3. Both men and women ranked ‘not liking confrontation’ highly. It is unclear from our question if this was confrontation during the joint reporting stage with the other expert witnesses, as opposed to the actual court process and conflict with the barrister. Many cases are settled after the joint reporting stage and before going to court. In the medico-legal session at the 2021 BOA Congress entitled, “Medico-legal Reporting – Why, How and When”, many of the guest speakers commented that they had rarely, if ever, had to attend court. Potential medico-legal experts should however recognise that the role of the expert witness in court is to aid the Courts’ understanding of the complexities of the medical world and not to advocate for one side or the other. So confrontation should not really be an issue.

Women ranked not having a suitable mentor and never being exposed in training within their top five answers. This lack of understanding of the medico-legal process should be addressed to encourage people into the speciality.

Women were more likely to note difficulties in balancing work life as a dissuading factor. When coupled with previous responses, that the advantages of medico-legal work are that it can often be done from home and is seldom, if ever an emergency, this may imply that female surgeons have greater responsibility for managing the home. Alternatively, the younger female surgeons may be more likely to have young family at home requiring more hands on care.

Why do people stop doing medico-legal work?

The majority of men who had stopped doing medico-legal work had retired. This makes sense with the older age of the men responding to this survey. The Royal College of Surgeons guidelines2 recommend that although continuing a medico-legal practice after retirement can be done, it should only be continued for a couple of years after, to avoid the risk of being out of date. We had only one female respondent who no longer did medicolegal work; her reason appeared to be related to difficulties within the speciality, citing demands on time and an adverse court judgement.

Why is diversity important in medico-legal work?

Matthew Syed in his book Rebel Ideas3 talks about cognitive diversity, where people with different perceptions, experiences, insights and thinking styles can bring an uplift in ideas. Medico-legal clients come with their own diversity. Some clients may feel more comfortable with a medico-legal professional who can understand their perspective. A more diverse groups of experts will have a greater collective cognitive diversity and therefore may drive a wider understanding of long term problems facing medico-legal clients. Although the expert witness has a responsibility to the Court rather than the client, being able to understand the client’s cultural background may help with giving a more informed opinion.

What conclusions can we draw from these results?

It is difficult to draw conclusions from the small numbers involved in this survey. There are some interesting findings that can be explored. These results can be used to encourage all genders to work as a medico-legal expert. There is commonality between the genders in why people go into medico-legal work, yet the differences in why people do not, are more interesting. Some of these appear to be related to misconceptions surrounding the work.

We know that the numbers of female consultants are increasing, from 2.9% in 2004 to 8% in 2020 according to the Department of Health and NHS Digital figures. The lag in the medico-legal profession may be exaggerated by the misconception that medico-legal work cannot be started within the first five years of practice. Although medical negligence work benefits from the extra experience, personal injury can be started at any stage.

The proportion of female expert witnesses is unlikely to exceed the percentage of doctors qualifying five years previously, although there are actions that can be taken to maximise the take-up within the available pool of potential candidates.

How can we attract more women into medico-legal work?

Registrar exposure

Trainees are generally not exposed to medico-legal practice. In some instances working for a Consultant who has a specific interest may give a brief glimpse into medico-legal work. However it is unlikely a full understanding of how the system works will be gained. Working with Deaneries and medico-legal professionals to provide teaching may improve understanding at the trainee level.

Mentorship

When someone decides they would like to pursue medico-legal work, it can be difficult to know where to start. There are plenty of commercially available courses, aimed at the medico-legal expert who has already started out. Having someone to guide and offer advice on simple things like how to bill for work and the best courses could have a great impact. Mentors can be in different regions at different stages of their careers, this reduces competition which may be one reason people do not offer to mentor others. Mentorship can continue through a medico-legal career not just at the start. There may be a role for the BOA to instigate a course such as, an introduction to medico-legal practice, which could point senior trainees and newly appointed consultants in the right direction. Several BOA Fellows have offered to act as mentors.

BOA Congress and speciality meetings

The 2021 BOA Congress’s medico-legal sessions this year were intended to encourage people into medicolegal reporting. The Congress is attended by medical students to Consultants. The sessions gave some insight into cross examination within a courtroom and guest speakers discussing how they set up their practice and their reasons for entering the profession. More events like this are planned, including the OTS Conference in 2022.

So by reducing some of the mystery surrounding medico-legal work and offering mentors we can increase the diversity of medico-legal expert witnesses.

References

- British Orthopaedic Association (2020). British Orthopaedic Association Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan 2020-2022. Available at: www.boa.ac.uk/about-us/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-andinclusion-strategy-and-action-plan.html.

- The Royal College of Surgeons of England (2019). The Surgeon As An Expert Witness – A Guide To Good Practice. Available at: www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/standards-and-guidance/good-practiceguides/expert-witness.

- Syed M, 2019. Rebel Ideas: The Power of Diverse Thinking. John Murray Press, London.