Current medico-legal considerations in the orthopaedic treatment of Jehovah’s Witnesses

Author: Simon Britten

Current medico-legal considerations in the orthopaedic treatment of Jehovah’s Witnesses

During the middle and late 19th century many religious study groups sprang up dedicated to examining the Bible closely to try to reconcile the diverse doctrines of the major Christian faiths and try to understand Biblical prophesies and their fulfilments. The modern day organisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses traces its roots back to one such group.

In 2020, Jehovah’s Witnesses worldwide numbered 8.7 million members actively engaged in various forms of public ministry. This number does not include children or those attending meetings. At their annual meeting to memorialise the death of Christ in spring 2020, there were approximately 18 million in attendance worldwide.

Jehovah’s Witnesses are not opposed to medicine and they seek out and appreciate quality professional medical care. They have a high regard for life and emphasise a healthy lifestyle. As a patient group they strive to be well disciplined and apt to follow clinical advice, including adhering to post-operative directions and rehabilitation. To some clinicians this may seem inconsistent with their refusal of the transfusion of whole blood and its primary components, when transfusion has an established place in modern medicine alongside many advancements in blood conservation and transfusion-alternative strategies. Witnesses are generally well informed and fully appreciate that their stance could be life threatening in extreme circumstances, so why is their viewpoint so strongly held?

Jehovah’s Witnesses state that their beliefs are Bible based and their stand against the transfusion of whole blood and its primary components is principally a scriptural stand and secondarily a medical stand. They note various references to blood throughout the Bible, and they see a great sensitivity to blood, animal or human, from God; on several occasions the use of blood in any way, be it dietary, commercial or otherwise is strictly proscribed. Such references can be found in the Old Testament – for example Genesis 9:3,4 and Leviticus 17:13,14, and in the New Testament – Acts 15:19,20. They believe blood is symbolic of life itself, and their wilful disregard of its sanctity could jeopardise future hopes beyond present existence. Their strength of feeling is therefore unsurprising.

Legal and ethical issues

Judge Cardozo in 1914 stated that “… every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what should be done with his body…”1 However, it has taken until the early 21st century for autonomy to supersede ‘doctor knows best’ paternalism. Legal and ethical support of the adult Jehovah’s Witness who refuses a blood transfusion can be found in the Human Rights Act, with Article 8, the so called ‘autonomy article’ – right to respect for family and private life; and Article 9 – the right to freedom of thought, belief and religion2. For the clinician faced with an adult’s refusal to accept a blood transfusion, there is a conflict between the clinician’s duty to preserve life, versus their duty to respect the right of an adult patient with capacity to make autonomous choices.

It is well established in medical law that an adult with capacity can decline treatment, even if in so doing it may lead to the death of the individual. In the case of Re T (Adult: Refusal of Treatment), Master of the Rolls Lord Donaldson stated – “… every adult has the right and capacity to decide whether or not he will accept medical treatment, even if a refusal may risk permanent injury to his health or even lead to a premature death.”3

On this basis, an adult Jehovah’s Witness with capacity has the right to decline a blood transfusion, even if they might die as a consequence. The decision to decline a transfusion of whole blood or any of its primary components may be recorded in advance in England and Wales by the use of an Advance Decision Document (ADD), which would take effect if the individual subsequently loses capacity to accept or refuse treatment. Such an advance decision must be in writing, witnessed, and must stipulate that it is to apply even if life is at risk. The ADD makes it clear that the individual refuses transfusions of whole blood and its primary components (red cells, white cells, plasma and platelets). Jehovah’s Witnesses also refuse autologous predonation of blood and the use of any sample of their blood for crossmatching. In Northern Ireland, Scotland (‘Advance Directives’) and the Republic of Ireland (‘Advance Healthcare Directives’), while there are some subtle differences in the relevant legal frameworks, the broad principles are similar.

Where an adult patient with a valid ADD loses capacity, and the treatment proposed is covered by the terms of the ADD, the clinicians must respect the provisions of the ADD and avoid transfusion of whole blood or its primary components, unless there is evidence that at the time of signing the individual did not in fact have capacity or evidence that they have subsequently changed their mind. The clinicians may institute other appropriate treatments unless specifically declined by the individual in Section 5 of the ADD. To proceed with a blood transfusion in the face of a valid ADD, i.e. without the individual’s consent, is unlawful, and may lead to jeopardy for the clinician with the courts and the regulator.

Where an adult patient loses capacity and there is no clear evidence of a valid ADD, treatment decisions must be made by the clinicians on the grounds of the patient’s best interests. However, when considering ‘best interests’, this does not only refer to their best interests from a clinical standpoint, but should also include consideration of any known cultural or religious beliefs and values4. Information provided by relatives, friends and the local Hospital Liaison Committee of Jehovah’s Witnesses can be extremely valuable. Even if it cannot be definitively proven that the individual had made an advance decision, but there are strong grounds to believe that they would have refused to consent to a specific treatment, the provision of that treatment may not be considered to be in their best interests and therefore would be unlawful.

Since 1991, Hospital Liaison Committees have been functioning in major cities in the United Kingdom, composed of Elders from various congregations of Jehovah’s Witnesses. They are trained to liaise between Witness patients, their families and clinical teams. They are available to provide support in all elective and emergency medical and surgical cases involving anaemia or haemorrhage via Hospital Information Services (Great Britain) 24-hour telephone 020 8371 3415, email [email protected].

Jehovah’s Witnesses readily accept that the law does not give parents unlimited medical decision making authority for their children, and they appreciate that surgeons cannot provide a 100% assurance that major blood components would not be used in the treatment of a minor. The Royal College of Surgeons’ guidance ‘Caring for patients who refuse blood’ notes that – “surgeons have a legal and ethical responsibility to ensure the wellbeing of the child … this must always be their first consideration; however, every effort must be made to respect the beliefs of the family and avoid the use of blood or blood products wherever possible.”5

In England and Wales young people over the age of 16 can give legally valid consent to treatment. ‘Gillick competent’ children under the age of 16 can give consent if they are considered to have a sufficient level of competency to understand the issues involved. However, the courts have been willing to overrule the refusal of specific treatments by young people under the age of 18 years old. Historically this willingness to overrule has been the outcome in the majority of cases of under-18s refusing blood. In Scotland, a cut off of 16 years old is consistent for both acceptance and refusal of treatments offered. In broad terms, the closer a young person is in age to the relevant age cut off point, the more weight the courts will give to the young person’s views.

In the case of planned surgery, there should be dialogue between the surgeon, anaesthetist, haematologist, child and family regarding the likelihood of life-threatening haemorrhage and possibility of blood transfusion, and the family’s position on the transfusion of blood as well as clinical strategies for avoiding transfusion. The HLC may assist in such discussions.

Following this discussion the multidisciplinary clinical team can consider whether they are prepared to proceed under the defined constraints. If not, they may wish to consider referral to another team with appropriate experience with such situations, if one exists. The multidisciplinary team may conclude that they can only proceed with the option available of providing a blood transfusion despite parental refusal, acting as they see it in the best interests of the child. This is not without impact to the family and the doctor-patient relationship. The parents may be prepared to give consent to a procedure for their child, on the basis of genuine assurance that the treating team will make optimal use of all appropriate transfusion-alternative strategies so as to respect their beliefs and only give a transfusion if absolutely necessary. Most techniques suitable in adults to minimise the likelihood of intra- and postoperative blood transfusion are applicable in children’s surgery. Should careful consideration and constructive dialogue between the family and treating clinicians fail to provide satisfactory resolution, the treating clinicians may apply to the Court of Protection for a Specific Issue Order (SIO) to provide legal sanction for a specific action, such as giving a blood transfusion, without removing all parental authority6.

In an emergency with significant risk to life and insufficient time to obtain an SIO from a court, if dialogue with the parents and young person is unsuccessful in obtaining consent, blood should only be given where absolutely necessary to prevent severe detriment to the child’s health. An SIO should be sought as soon as possible. But note that the Royal College of Surgeons give the following advice – “If a child needs blood in an emergency, despite the surgeon’s best efforts to contain haemorrhage, it should be given. The surgeon who stands by and allows a ‘minor’ patient to die in circumstances where blood might have avoided death may be vulnerable to criminal prosecution.”7

The point of contact for the surgeon and anaesthetist wishing to obtain an emergency SIO from the Court of Protection varies between hospitals and the time of day. It may be any one of the hospital’s legal department, department of clinical risk, the senior hospital site manager on call, or senior nurse covering the site; and in turn they will contact the hospital solicitor to apply to the Court of Protection.

Treatment strategies and options

While Jehovah’s Witnesses decline transfusion of whole blood and primary blood components, various other derivatives of primary blood components may be accepted by the Witness patient as a matter of personal choice. Such derivatives include albumin, coagulation factor concentrates such as cryoprecipitate and fibrinogen, immunoglobulins and fibrin glue.

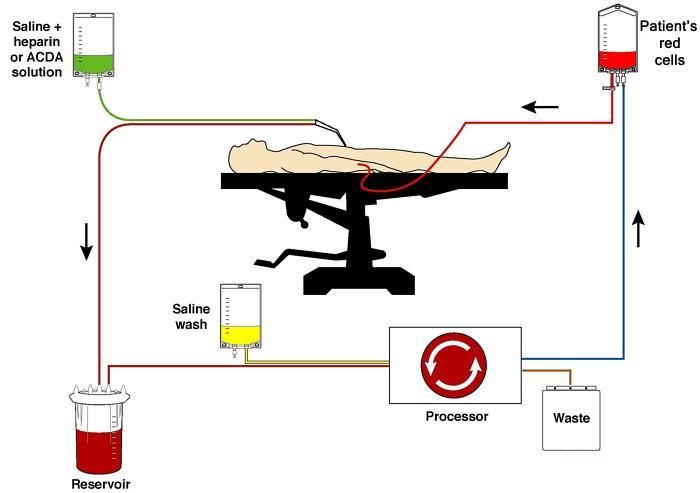

Certain blood management techniques may also be considered as part of personal choice by the Witness, including use of cell salvage, acute normovolaemic haemodilution, and post-operative blood salvage from wound drains. Other advanced technologies considered to be a matter of personal choice include haemodialysis, cardiopulmonary bypass, and organ transplantation. Jehovah’s Witnesses are prepared to accept recombinant coagulation factor concentrates, interferons and interleukins; and drugs such as recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) and iron, which are not derived from blood. The use of human tissue, including bone grafting, skin grafting and free tissue transfer are potentially acceptable.

Patient Blood Management (PBM) is a collaboration between the National Blood Transfusion Committee and NHS Blood and Transplant Service, and is an evidence-based, multidisciplinary approach to optimising the care of all patients who might need transfusion. It involves avoiding unnecessary blood transfusion, the diagnosis and management of anaemia, preoptimisation where possible, meticulous surgical haemostasis, cell salvage, the use of anti-fibrinolytic agents to reduce bleeding, and the involvement of the patient in the decision making process8. While the principles of PBM are advocated for all patients and aimed at the conservation of blood and its appropriate use rather than its absolute avoidance9, these principles have greatly assisted clinicians in the safe and effective treatment of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Detailed guidelines for patients who refuse blood transfusion in elective surgery where blood loss of >500 ml is anticipated, have been produced by the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland10. Pre-operatively consideration should be given to optimising red cell mass and discontinuing or substituting anticoagulants and anti-platelet agents. Unnecessary blood tests should be avoided and consideration given to use of paediatric sampling tubes. Oral or intravenous iron and rHuEPO may be valuable.

Useful intra-operative techniques may include acute normovolaemic haemodilution, controlled hypotension, epidural anaesthesia, maintenance of normothermia, point of care testing for arterial and venous blood gas sampling, thromboelastometry, use of a cell saver, fibrin sealants, administration of intravenous tranexamic acid and use of desmopressin. While Witnesses do not accept primary blood components such as fresh frozen plasma or platelets, useful adjuncts to haemorrhage control may include cryoprecipitate and other coagulation factors, depending on individual Witness preference. Witnesses note that when considering intraoperative autologous techniques, in principle it is not essential to keep the Witness in continual contact with their own blood by means of a continuous loop or circuit.

Postoperatively blood tests should be minimised and the routine use of anticoagulants carefully balanced against the risks of additional blood loss. Following tourniquet use, post-operative cell salvage may be considered. A further dose of intravenous tranexamic acid may also be of benefit. Many of the above techniques are directly transferable to emergency scenarios.

Summary

- Jehovah’s Witnesses do not accept the transfusion of whole blood or its primary components.

- The acceptance of derivatives of primary blood components and of techniques such as cell salvage are matters of personal choice.

- Adults with capacity may refuse treatment, even if it may lead to their death, and refusal in advance of blood transfusions can be set out by means of a signed and witnessed Advance Decision Document.

- The management of children of Jehovah’s Witnesses may give rise to some ethical challenges, which can often be resolved by dialogue between the family and treating team. On occasion it may be necessary to seek a decision from the Court of Protection. The Hospital Liaison Committee may be of assistance.

- Patient Blood Management has been developed to optimise care of all patients and minimise transfusion requirements, and optimal and rigorous use of PBM principles are useful in the management of Jehovah’s Witnesses, in elective and emergency settings.

References

- Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital [1914] 105 NE 92 (N.Y. 1914).

- The Human Rights Act 1998, Chapter 42. London: Stationery Office.

- Re T (Adult: Refusal of Treatment) [1993] Fam 95, at 115

- General Medical Council (2020). Personal beliefs and medical practice (updated November 2020). Available at: www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/personal-beliefs-and-medical-practice

- Royal College of Surgeons of England (2016). Caring for patients who refuse blood. Available at: www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/rcs-publications/docs/caring-for-patients-who-refuse-blood.

- Children’s Act 1989, Chapter 41, Section 8, Specific Issue Orders. Available at: www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/41/contents/enacted.

- Royal College of Surgeons of England (2016). Caring for patients who refuse blood. Available at: www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/rcs-publications/docs/caring-for-patients-who-refuse-blood.

- Joint United Kingdom Blood Transfusion and Tissue Transplantation Services Professional Advisory Committee. Patient Blood Management. Available at: www.transfusionguidelines.org/uk-transfusion-committees/national-blood-transfusion-committee/patient-blood-management.

- Clevenger B, Mallett SV, Klein AA, Richards T. Patient blood management to reduce surgical risk.

Br J Surg. 2015;102(11):1325-37; discussion 1324.

- Klein AA, Bailey CR, Charlton A, Lawson C, Nimmo AF, Payne S, et al. Association of Anaesthetists: anaesthesia and peri-operative care for Jehovah’s Witnesses and patients who refuse blood. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(1):74-82.