Competency

By Simon Donell

Retired Orthopaedic Surgeon, Stapley, Somerset

When I qualified in 1980, the average life expectancy of a surgeon retiring at 65 years old was three years; at 60 years old, it was 10 years. As you can see, life was so much better in the olden days. I retired at 60 years old.

I started in surgical training when the Royal College of Surgeon’s examinations were filters to select candidates to continue to becoming consultant surgeons. Nowadays we recognise the process as systemic bias. Comments made to me at that time by senior surgeons confirmed that the bias was overt. Essentially you were trying to join a club. I had the advantage of being a white male.

At the end of the 1990s, I was a member of the committee for the Locomotion module (Orthopaedics and Rheumatology) of the University of East Anglia’s bid for a Medical School, the level of knowledge and competency for the undergraduates to pass the module was set at that needed by a General Practitioner in diseases of the musculoskeletal system. The committee consisted of a patient, a GP, two rheumatologists, and me.

Now the problem is that there are three Types of Knowledge:

- Essential

- Interesting

- Trivial

As such, for the rheumatologist vasculitis was essential knowledge, whereas it was only interesting for the GP. Vasculitis was not formally included in the curriculum. The other problem was the majority of musculoskeletal disorders are trauma and degenerative arthritis. Rheumatological conditions are relatively rare. The Norwich course has a high input of medical student training by GPs. Both back pain and ankle sprain teaching were placed in primary care. In orthopaedics, attendance in theatre to see a joint replacement, much to my colleagues horror, was voluntary (not essential for general practice). Curiously all students went to theatre. However a significant percentage failed to attend the compulsory lectures on a Wednesday morning. My conclusion was that students should be treated as adults.

Medical education requires both knowledge and skills. In surgical training the skills needed include the ability to operate. In the early 2000s I was an examiner for the Intercollegiate Specialty Board in Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery. We were trained and we were assessed. Gone were the days of being asked random trivia (“Who was Coudé?”). The candidates are expected to be competent at a level to be a trauma and orthopaedic surgeon on their first day in practice. My advice to candidates was, when asked a question consider whether the question is testing incompetency, competency, or a potential gold medal e.g. “Which nerve is involved in carpal tunnel syndrome?” versus “When would you consider asking for nerve conduction studies in carpal tunnel compression?” versus “How does the median Nerve Sensory Amplitude vary between diabetic patients and carpal tunnel syndrome patients?”. The last one is not a competency question. Ignorance of the first is an automatic fail.

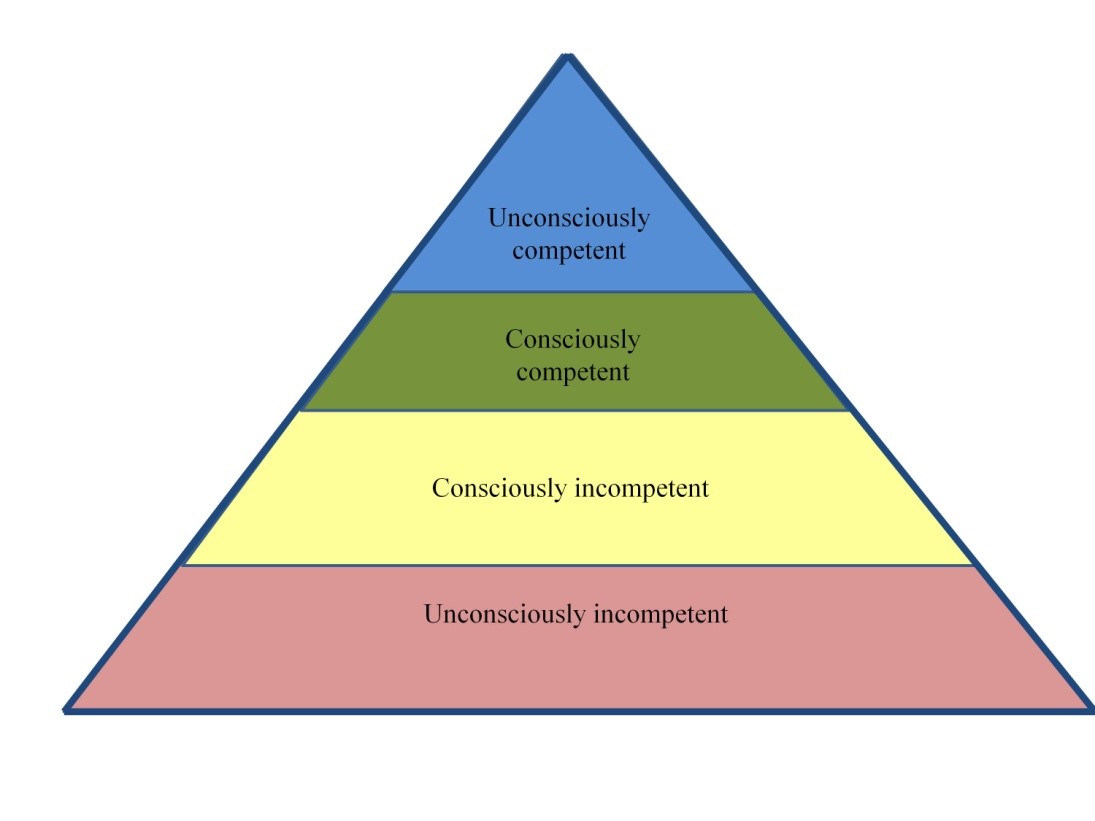

When undergoing skills training one passes through four psychological stages of competency (see Figure 1): unconsciously incompetent where you do not know what you need to know, consciously incompetent where you know that you need to know, but do not know it, consciously competent where you know what you need to know, and unconsciously competent where you know it but do not need to think about it. As in Figure 1, this is often considered as a pyramidal progression.

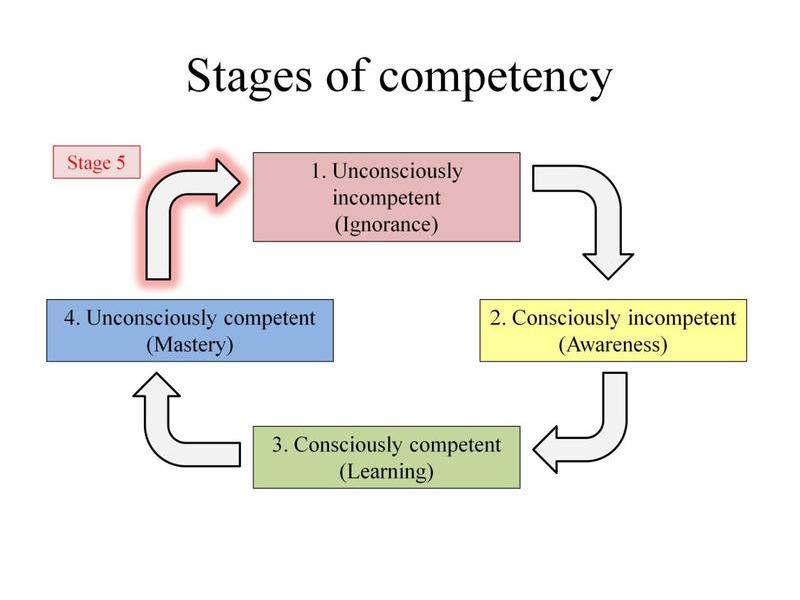

However when training in a manual skill, such as surgical procedure, driving a car, or playing tennis, it is worth remembering that the stages form a circle with the fifth stage being to return to unconsciously incompetent. Studies suggest that this begins from the age of 60 years. Anyone with an elderly relative who drives a car will know how difficult it is for them to understand that they have become incompetent. “I have been driving for 60 years and I know how to do it”. The late Duke of Edinburgh was forced to stop driving in his 90s when he T-boned a car driving out of Sandringham. My mother, aged 89 years old, did the same thing coming out her GP surgery car park about 3 months later... She greatly admired Prince Philip and so accepted that she should hand in her licence. The local garage no longer repaired her car from all the dings and crashes she was having on a bimonthly basis.

The five stages of competency are shown in Figure 2. It should be noted that to get to Stage 4 from Stage 3 involves experiential training i.e. performing common procedures many times. As a trainee at registrar level (cf ST4), in a hospital where I trained there was a grand round on a Friday morning. The personnel consisted of the four consultants, three registrars, three housemen, ward sister, staff nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, and social worker. Each patient was seen and radiographs reviewed. The dynamic hip screw had just been introduced in trauma practice for hip fracture management. In the previous hospital I had worked at I preformed the very first DHS. I had an SHO assistant and the operating manual out. There was not even a rep (Account Manager) present. I had never seen any literature nor been told about it. I was told to read the manual and it would be fine. The operation took over three hours. There was no image intensifier, only wet films. These were taken when the fracture was reduced, then when the guidewire was in, and finally when the implant was in. To my amazement the patient was able to get up and walk the next day. This never happened with the old MacLaughlin pin and plate. I concluded the DHS was a brilliant implant since the most incompetent surgeon could get a good result. Back to the grand round, there was always the humiliation of the implant position seen on the post-operative radiograph’s lateral view. One of the consultants, who tended to express his views forcefully, was very keen on golf. I learned that describing the screw position in the femoral head as a golf shot to the green saved my bacon. There was the hole-in-one, on the green, in the light rough, in the heavy rough, and out-of-bounds another ball taken. The original DHS system had a lug in the barrel of the plate, and a slot on the screw which aligned with the lug. Unfortunately there was an extension piece to the screw to be placed when after insertion it was deeper than the lateral bony cortex. It could be placed at 180° as well as correctly at 0°. When the barrel of the plate was placed onto the screw extension, on hammering the screw it ended up in the pelvis, lost when the extension piece was removed. So a second screw was placed in. The lateral compression screw then was used to stop the new screw continuing to migrate into the pelvis. You only make that mistake once. One of the calmer consultants whispered to me on the ward round, “Don’t worry, we only expect you to get it right when you have done a hundred.” Subsequently I found out that he had once, in a total hip replacement, cemented the femoral stem outside the lateral cortex of the femur, demonstrated to all on the post-operative radiograph. Each registrar spent one-year at the hospital, but the turnover was every six months. After six months my job was to teach the next registrar the operations for hip fractures – “see one, do one, teach one”. Sometimes the “see one” was missed and so you read the operative manuals. It helped enormously to know the anatomy. Operative training has now moved on from independent practice at Stages 1 and 2.

Figure 2. The five stages of skills competency.

Stage 5 is now the time where patients become at risk. Mandatory retirement for surgeons at 65 years old has now stopped, but all surgeons should be aware that their skills inevitably diminish from around 60 years old. If you have superb surgical skills you may remain competent into your 80s. But if your skills are only adequate, then you may be incompetent by 65 years old. The first important point to be aware of is that you will not be aware of it. The people around you will be. The second important point is that you do not want to retire from surgical practice soon after you have T-boned a patient.