Children’s Health Ireland and the COVID-19 Catalyst: Reconfiguration of a Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgery Department in the Current Crisis

By Murphy EP, O’Sullivan MD, O’Toole PJ, Kelly PM, Noel J, Kennedy J, Kiely PJ, Molloy A, Moore DPChildren’s Health Ireland, Crumlin, Cooley Road, Dublin, Ireland

Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Published 27 April 2020

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative pathogen responsible for coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has established itself as the most devastating pandemic in contemporary medical history. Healthcare workers caring for patients with COVID-19 are at high risk of infection1 and the current health crisis has created a challenging working climate. COVID-19 has changed the way health systems are providing care throughout the world. Children’s Health Ireland (CHI) at Crumlin has adapted by evaluating and reconfiguring the current operating systems. In this narrative review we aim to describe the response of our Paediatric Orthopedic Department with respect to service redesign.

Departmental overview

CHI at Crumlin is the largest paediatric hospital in Ireland, and is responsible for tertiary and quaternary referrals. There are over 38,000 emergency attendances per annum, 77,500 out patient appointments, 21,500 surgery procedures and 20,500 day case procedures. CHI at Crumlin provides layered care, in a number of settings. The paediatric orthopaedic department oversees outpatient care at two separate hospital sites, provides subspecialist care for all orthopaedic surgical conditions and provides an on-call emergency referral service for trauma. The catchment area is nationwide for subspecialist referrals. There were a number of stakeholders to take into consideration. The department has eight consultants (seven of whom take trauma call), nine registrars, two senior house officers (SHOs) and a number of allied health care professionals. Care in Crumlin was traditionally consultant delivered and supported by ancillary staff.

National context

Health care systems are not known for their dynamic actions, often being accused of being reactive rather than proactive.

The first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in Ireland on February 29th, with the first death occurring on March 11th, schools and universities were closed on March 12th and on March 27th a nationwide lock down was announced. At the time of reporting there are 19,262 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with 1,087 deaths and 277 confirmed cases occurring in a population less than 14 years of age in Ireland. The paediatric cohort has a number of unique considerations which must be taken into account during service reorganisation. Paediatric cases of COVID-19 accounted for 2% of cases in China2, and most infected children appear to have a milder clinical course with asymptomatic infections not uncommon3.

The department had to factor in manpower reorganisation, elective commitments, trauma commitments and work within the constraints of the new physical distancing frame-work. The main stakeholders included patients, parents, doctors, nurses, administrative support, theatre staff and allied health care professional staff involved in rehabilitation and ongoing continued service delivery.

Departmental response

The swift spread of COVID-19 and increasing escalation of recommendations lead to the rapid reconfiguration of the CHI Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgery Department. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended a series of protective measures including increasing awareness of hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, and physical distancing. The first measure to be implemented was social distancing. This lead to a seismic change in the working relationships and the re-ordering of teams. The department heads were required to undertake a review of the process maps of each working area, to understand the roles of all the staff members involved, and to highlight the value brought by each interaction. This ‘lean’ approach enabled the implementation of a ‘pods’ based system. Lean methods involve process improvement, empowerment of workers and the elimination of mistakes and waste4. The business world has established credentials in scaffolding teams, however the CHI Crumlin team had to adopt this philosophy without the preparatory groundwork.

Personnel and pod teams

At present social distancing and hand hygiene are our best tools to reduce transmission of the COVID-19 virus, until a vaccine is developed5.

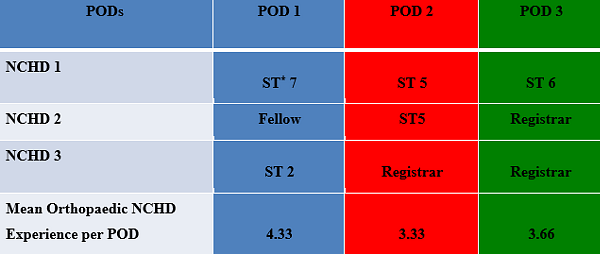

All weekly face to face team meetings, (trauma audit, teaching, preoperative elective case conference, preoperative spinal cases meeting and the research meeting) were cancelled and transitioned to an online platform. A ‘pods’ system was introduced. This meant dividing the orthopaedic group into clinically autonomous teams, to facilitate cover in the event of a team member contracting COVID-19. The consultant continued to take trauma call, for seven days at a time, known as the ‘Hot Week’. For the registrar cohort of nine with two SHOs , we split into three groups of three with an equal distribution of experience. This allowed for one registrar to be on call, one in trauma theatre, and one registrar in clinic.

One area of care that represents a crossover point between pods is the morning ward-round. To mitigate the risk of potential transmission at this time, as well as employing social distancing, the responsibility of seeing inpatients on the morning round is divided. Encrypted communication via a smartphone application, is used to convey relevant information regarding inpatient care. Figure 1 shows the division of the orthopaedic group into the respective pods.

Figure 1. Pod system

*NCHD – Non consultant hospital doctors ST* Surgical Trainee

Triage of clinics

Elective clinics were cancelled as a response, the appointments were deferred for two months. All the affected patients charts were reviewed, and documentation of the outcome was recorded by entering ‘COVID-19’ stickers in the records. Patients that required ongoing review (frame corrections, Ponseti casts, urgent post-operative patients) were allocated time during the clinics, or a virtual review was arranged.

All offsite trauma clinics were centralised to Crumlin. The appointments are staggered over a five-hour period from 12 - 5 pm, with just one accompanying adult allowed. This allows physical distancing in the waiting room and the x-ray department. The consultant led virtual fracture clinics (Trauma Assessment Clinics) have continued, as they have been shown to reduce the volume of patient attendance in the trauma clinic by 65-70%6.

Education and audit for our safety

Hospital management distributed daily memos via email to keep all employees abreast of policy changes. They have also organised multiple demonstration of correct application and removal of personal protection equipment (PPE), as this has been shown to be the highest risk time for transmission of particles potentially harboring COVID-197. We have adopted a ‘buddy system’ at the end of cases for the removal of PPE in theatre, with the steps readily visible with a laminated poster. The department has continued to hold twice weekly teaching sessions via the online platform. Audit is an important pillar of professional practice and the department has continued to have its weekly trauma audit meeting via an online platform. This is to ensure that the culture of safety is still promoted among the department.

Surgery

Outcomes in surgery have often been broken down into patient risk factors, surgical skill, the operation profile and the manipulation of this combination hopefully leads to a successful outcome8. Paediatric orthopaedic surgery requires a knowledge of the natural history of conditions, application of this knowledge to different treatments and understanding the nuances of each clinical interaction. Crumlin offers a daily trauma and elective service. It was decided there would be a more conservative approach to providing care; to limit harm to patients, staff and all involved, while the health crisis was in evolution9.

Trauma surgery

The priority in CHI was the protection of a trauma service while taking stock of ongoing personnel availability and PPE requirements. CHI Crumlin has nine operating theatres. Orthopaedics has variable access to a trauma theatre, with competing access to the emergency theatre on other days. The hospital response was to curtail the individual specialty theatres, and to use between two to four theatres on a daily basis. This lead to increased need for inter-disciplinary communication with respect to highlighting priority cases, equipment needs, scheduling and staggering same day arrival times.

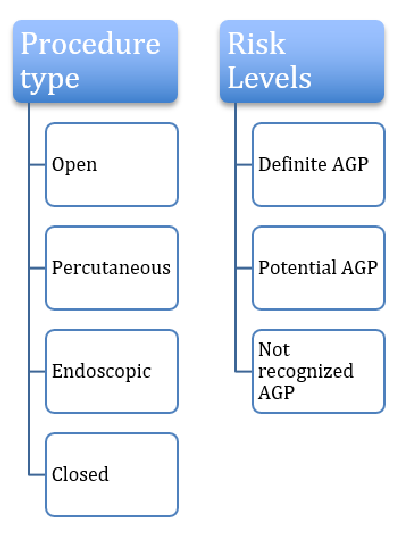

The orthopaedic team reviewed the information available with respect to risks about aerosol generating procedures (AGP) to guide PPE usage and requirements. This lead to a conceptual change with respect to categorising cases and attempting to ascribe a risk level. This was a pragmatic approach and risk level was not based upon published guidelines, as none are currently available, but rather upon the experience in Crumlin at present.

Figure 2. Categorisation of procedures in Crumlin

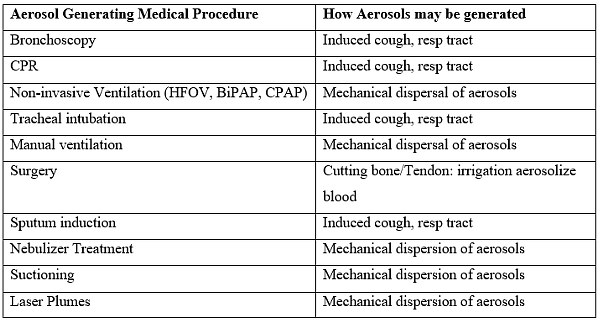

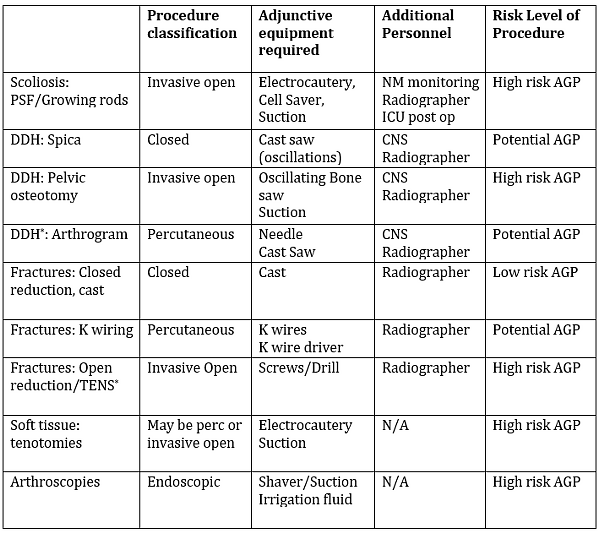

The WHO has produced literature on the definition of AGPs however it does not provide evidence with respect to orthopaedic procedures10,11. Table 1 highlights the available evidence with respect to AGPs in the hospital setting. This led the team to consider the components of AGPs in our practice and the potential implications for the provision of care in Table 2. Many factors can influence the risk level including adjunctive equipment, type of anaesthesia, manipulation of the airway and the length of the case12,13. Table 2 highlights some of the concerns but should not be taken as official guidelines due to the constant evolution of information with respect to COVID-19.

Table 1. WHO guidelines 2014 AGPs

Table 2. Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgery considerations

*DDH= Developmental Dysplasia of Hip

*TENS: Titanium Elastic Nailing System

Specific recommendations to reduce risks:

- Use smoke extractor with electrocautery.

- Limit suction if possible.

- Consider if scissors can be used instead of plaster saw.

- Do not use pulse lavage.

- Limit personnel in the room.

- Lei et al. demonstrated 20% mortality if asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 undergo elective surgery13.

Specific risks with power tools

- Drills/Reamers/Oscillating saws11,14-19.

- K wires: both the wire if it is bloody, and the action of going in and out of bone20,21.

- Suction: rigid worse than soft but is acknowledged to be AGP in oropharynx and with blood11,15,22.

- Plaster saw: generates significant dust particles which travel around room. If patient has COVID droplets on body/cast or faeces particles on a spica cast, then theoretical risk23,24.

- Arthroscopy: the irrigation and suction and shavers theoretical risk with removing and inserting14,25.

Elective surgery

The elective surgery practice in Crumlin encompasses a wide range of procedures from infantile hip pathology to adolescent scoliosis. Currently elective surgery is not being undertaken due to PPE restrictions, limited staff availability and restricted access to ICU to facilitate the need for a potential ‘surge’ in cases and decanting from adult hospitals9,26,27. Crumlin is not alone in this dilemma28. The American College of Surgeons have issued guidelines on how to triage elective practices29,30.

The department is triaging the complex care needs of the most urgent cases to ensure harm does not befall these vulnerable patients. Some of the issues currently being considered include PPE requirements for all staff, the need for ICU admissions and rehabilitation on the ward. These decisions cannot be made in isolation. Many departments have seen redeployment to support the adult hospitals, with remaining staff covering a broader remit than before.

Mental health and morale considerations

A common theme emerging is how departments and teams are maintaining morale in these uncertain times. It is acknowledged that COVID-19 is highly contagious and that a certain percentage of frontline staff will contract the virus31, with 25% of cases occurring in healthcare workers in Ireland.

Staff considerations

In Crumlin, the team has multiple modes of communication through which concerns may be raised. These include a cross platform messenger, team emails and regular interactive virtual meetings. The hospital has a psychological support help line which all staff are encouraged to access as needed. Other measures include ensuring food is available to the front-line staff, car parking is subsidised and that staff have daily access to the most up to date information has proven pivotal in boosting morale. A new application ‘My CHI’ was developed to enable all staff working in Crumlin to access guidelines, recommendations and internal memos remotely. A ‘Balint’ group has been set up by the hospital to facilitate the discussion of matters of concern32. The teams have prepared by benefiting from simulated responses to performing interventions in COVID-19 positive patients33.

Patient considerations

The patient experience has changed in Crumlin. The play rooms are closed, patients are isolated in single rooms and only allowed one parent to stay to comply with physical distancing recommendations. An attempt to reduce fear surrounding PPE has led to the placement of signs in all patient rooms of doctors and nurses dressed in PPE34. This familiarity is hoped to normalise the appearance of the ‘masks and gowns’. Toys, video units and play stations have been placed into each individual room, as supplies allow, to attempt to create a stimulating environment.

Ethical considerations

A report from UNICEF (Bergman 2020) considered some of the ethical considerations surrounding the paediatric population in the COVID-19 crisis35. These include the increased need for safeguarding and the increased vulnerability of a certain subset of patients including those with physical or mental disabilities. Non accidental injuries (NAI) have been shown to be increasing in the current times36. Our roles as health care providers means we must have a heightened awareness of the possibility of NAI at present. Guidance from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland37 mainly focuses on the practical issues with respect to PPE, but an awareness of the vulnerability of the paediatric population is important.

Conclusion

The Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgery team in Crumlin has undergone a seismic shift in terms of departmental reorganisation. Lean process management has been implemented, with a focus on incorporating value for all stakeholders. The key tenet is to provide ongoing safe, high quality care within the current restrictions, while planning for the future. This has meant appropriate personnel distribution and PPE equipment usage, while attempting to plan for an uncertain future in a constantly shifting environment. Morale is important and continued communication across all levels has led to good inclusivity throughout the department. Some questions which remain unanswered include the classification of AGPs in orthopaedic surgery, how best to re-introduce elective practice, with a focus on PPE shortage and safety. We welcome any commentary on this contentious issue.

References

- Chang D, Xu H, Rebaza A, Sharma L, Dela Cruz CS. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(3):e13.

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Coronavirus Infections in Children Including COVID-19. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(5):355-68.

- Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, Zhang J, Li YY, Qu J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1663-5.

- Sethi R, Yanamadala V, Burton DC, Bess RS. Using Lean Process Improvement to Enhance Safety and Value in Orthopaedic Surgery: The Case of Spine Surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25(11):e244-e250.

- Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High Contagiousness and Rapid Spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7).

- Mackenzie SP, Carter TH, Jefferies JG, Wilby JBJ, Hall P, Duckworth AD, et al. Discharged but not dissatisfied: outcomes and satisfaction of patients discharged from the Edinburgh Trauma Triage Clinic. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(7):959-65.

- Rodrigues-Pinto R, Sousa R, Oliveira A. Preparing to Perform Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery on Patients with COVID-19. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 Apr 10. [Epub ahead of print].

- Vincent C, Moorthy K, Sarker SK, Chang A, Darzi AW. Systems Approaches to Surgical Quality and Safety: From Concept to Measurement. Ann Surg. 2004;239(4):475-82.

- Stahel PF. How to risk-stratify elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic? Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14:8. eCollection 2020.

- World Health Organisation (2020). Coronavirus. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus.

- World Health Organisation (2020). Infection prevention and control of epidemic and pandemic- prone acute respiratory infections in health care. WHO guidelines. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112656/9789241507134_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Heffernan DS, Evans HL, Huston JM, Claridge JA, Blake DP, May AK, et al. Surgical Infection Society Guidance for Operative and Peri-Operative Care of Adult Patients Infected by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2020 Apr 20. [Epub ahead of print].

- Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, Chen C, Chen J, Mei W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Apr 5:100331. [Epub ahead of print].

- Health Protection Surveillance Centre (2013). Infection prevention and control of suspected or confirmed influenza in healthcare settings. [Aerosol generating procedures (AGPs)]. Available at: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/respiratory/influenza/seasonalinfluenza/infectioncontroladvice/File,3628,en.pdf.

- Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e35797.

- Pluim JME, Jimenez-Bou L, Gerretsen RRR, Loeve AJ. Aerosol production during autopsies: The risk of sawing in bone. Forensic Sci Int. 2018;289:260-267.

- Nogler M, Lass-Flörl C, Ogon M, Mayr E, Bach C, Wimmer C. Environmental and body contamination through aerosols produced by high-speed cutters in lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(19):2156-9.

- Judson SD, Munster VJ. Nosocomial Transmission of Emerging Viruses via Aerosol-Generating Medical Procedures. Viruses. 2019;11(10).

- Department of Health Scotland (2020). Aerosol Generating Prodecures. Available at: https://hpspubsrepo.blob.core.windows.net/hps-website/nss/2893/documents/1_tbp-lr-agp-v1.pdf.

- Yeh HC, Turner RS, Jones RK, Muggenburg BA, Lundgren DL, Smith JP. Characterization of Aerosols Produced during Surgical Procedures in Hospitals. Aerosol Sci Technol. 1995;22(2):151-61.

- Heinsohn P, Jewett DL, Balzer L, Bennett CH, Seipel P, Rosen A. Aerosols Created by Some Surgical Power Tools: Particle Size Distribution and Qualitative Hemoglobin Content. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1991;6(9):773-6.

- Awad ME, Rumley JCL, Vazquez JA, Devine JG. Peri-operative considerations in Urgent Surgical Care of Suspected and Confirmed COVID-19 Orthopaedics Patients: Operating Room Protocols and Recommendations in the Current COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020 Apr 10. [Epub ahead of print].

- Wytch R, Ritchie IK, Clayton R, Gregory DW, Wardlaw D. Dust emission during cutting of polyurethane-impregnated bandages. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1988;12(3):155-60.

- Antabak A, Halužan D, Chouehne A, Mance M, Fuchs N, Prlić I, et al. Analysis of Airborne Dust as a Result of Plaster Cast Sawing. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56(4):600-8.

- Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol-Generating Procedures and Risk of Transmission of Acute Respiratory Infections: A Systematic Review. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/M0023__Aerosol_Generating_Procedures_e.pdf.

- Coimbra R, Edwards S, Kurihara H, Bass GA, Balogh ZJ, Tilsed J, et al. European Society of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES) recommendations for trauma and emergency surgery preparation during times of COVID-19 infection. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020 Apr 17:1-6. [Epub ahead of print].

- Fillingham YA, Grosso MJ, Yates AJ, Austin MS. Personal Protective Equipment: Current Best Practices for Orthopaedic Teams. J Arthroplasty. 2020 Apr 20. [Epub ahead of print].

- British Orthopaedic Association (2020). Emergency BOAST: Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-boasts-combined.html.

- Awad ME, Rumley JCL, Vazquez JA, Devine JG. Peri-operative considerations in Urgent Surgical Care of Suspected and Confirmed COVID-19 Orthopaedics Patients: Operating Room Protocols and Recommendations in the Current COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020 Apr 10. [Epub ahead of print].

- American College of Surgeons (2020). Local Resumption of Elective Surgery Guidance. Available at: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/resuming-elective-surgery.

- Guo X, Wang J, Hu D, Wu L, Gu L, Wang Y, et al. Survey of COVID-19 Disease Among Orthopaedic Surgeons in Wuhan, People’s Republic of China. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 Apr 8. [Epub ahead of print].

- Roberts M. Balint groups. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(3):245.

- Sørensen JL, Østergaard D, LeBlanc V, Ottesen B, Konge L, Dieckmann P, et al. Design of simulation-based medical education and advantages and disadvantages of in situ simulation versus off-site simulation. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):20.

- Chow CHT, Van Lieshout RJ, Schmidt LA, Dobson KG, Buckley N. Systematic Review: Audiovisual Interventions for Reducing Preoperative Anxiety in Children Undergoing Elective Surgery. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(2):182-203.

- Berman G. Ethical Considerations for Evidence Generation Involving Children on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available at: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/1086-ethical-considerations-for-evidence-generation-involving-children-on-the-covid-19.html.

- Baird E. Non-accidental injury in children in the time of COVID-19 pandemic. The Transient Journal. April 2020. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/non-accidental-injury-in-children-in-the-time-of-covid-19-pandemic.html.

- Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (2020). Clinical Guidance for Surgeons. Availabe at: https://www.rcsi.com/dublin/coronavirus/surgical-practice/clinical-guidance-for-surgeons.