Challenges and overcoming them in orthopaedics

By John Grice

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Great Western Hospital NHS Trust and BMI Healthcare, Swindon

Training

Surgical training has always been very competitive. However, nowadays there seems to be even more pressure on trainees to be the model professional. The trainee must have completed his/her other surgical exams, published journal articles, completed audits and developed good patient care on the wards, all before even being given the opportunity to embark upon recognised specialist training programmes. Academia needs to be coupled with fulfilling the requirements of the Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme website (see www.iscp.ac.uk) and gaining the best surgical technical experience in minimal time. Is it possible to fulfil all the requirements of a trainee to achieve one of those elusive training posts while maintaining a life outside the workplace? Can an individual have a significant interest outside the hospital and manage the acquisition and completion of a training number followed by gaining a suitable consultant post?

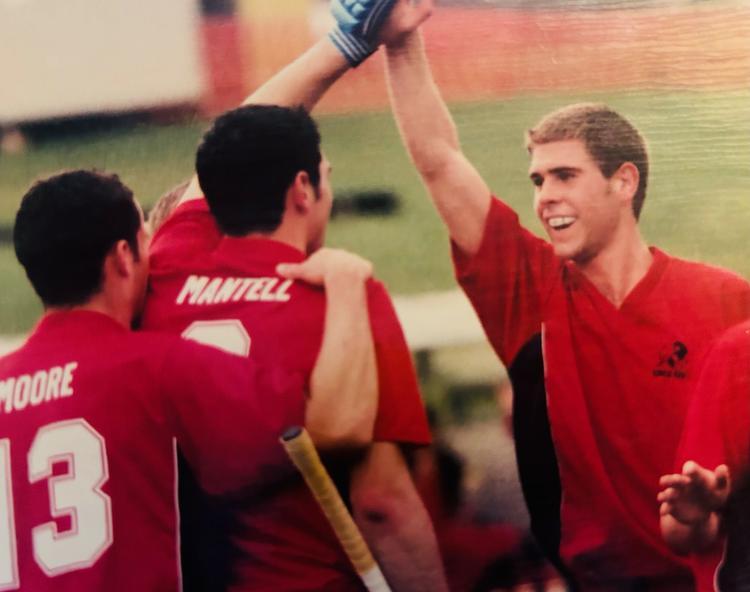

In the past there has been a string of top sportsmen and women who have juggled their surgical training with sports training and competition and have represented their country successfully. Taking my preferred sport, hockey, as an example, in 1988 Richard Dodds captained Great Britain to an Olympic gold medal. This was no small feat. However, he achieved this while being an orthopaedic registrar. How was this possible? When asked, he simply states: ‘I trained during the week in my own time and played at weekends’. He ‘manipulated the rota’ and attended 50% of the time in the two months leading up to the 1988 Olympics. He then opted to be ‘unemployed for August and September’ during the games themselves (personal communication). As you can imagine, achieving an Olympic gold takes a long build-up of hard work and training. Dodds’s first Olympic games (Moscow 1984) were in the first two weeks of his house officer year. Consultants at the time allowed him a little more time off than his quoted annual leave in which to train. The team achieved a silver medal. This achievement encouraged the group of players to work and train even harder over the subsequent four years, while Dodds was passing his MRCS and first part of the FRCS. The sport did not take away from Dodds’s surgical training, nor vice versa. Infact, he states that there is no doubt that the experience of international sport, training, teamwork and dedication aided his surgical career.

In contrast, a little more recently, I attempted to carry on competing at international level at hockey throughout my house officer year and found it impossible. What had changed? It may have been simply my innate lack of ability, but I’d like to think it was largely because the goalposts had moved! The situation is complex but includes the facts that training for sport had become more rigid and scientific, requiring far more face-to-face training time of the individual athlete with coaches and sports science trainers. However, things have also changed in surgical training. The time frame of training Old-style SHOs often spent up to six years in junior-level training. This period frequently included time taken out to undertake formal research, resulting in higher degrees such as an MD, MS or PhD. It also allowed trainees to do SHO posts in related surgical specialities: for orthopaedics it was considered desirable to have done SHO posts in general, plastics, neurosurgery and/or cardiothoracics, as part of a rotation. Now things have streamlined even more and Speciality training at junior level is shorter and more concentrated in a specific speciality.

Consultant work; my thoughts on successfully starting out

I am a foot and ankle consultant with an interest in sports injuries at a busy hospital, The Great Western Hospital (GWH) Foundation Trust. My consultant colleague at GWH is married to a half Japanese man. She introduced me to the concept that our job can and should allow Ikigai. Ikigai is a Japanese word whose meaning translates roughly to a reason for being, encompassing joy, a sense of purpose and meaning and a feeling of well-being (Figure 1). The word derives from iki, meaning life and kai, meaning the realisation of hopes and expectations. If balanced correctly, we can achieve this in our NHS practice but it occasionally requires a transformation in your job planning and service provision and is facilitated by good decision-making.

Figure 1

Carefully select where you live and work as you can not move your chosen hospital and your family and support network need to be happy in an area. If they are not engaged and satisfied in an place to live, you will not be also. In my opinion, long term commuting over distance is not an easy thing to do when starting out as a consultant. Try to pick your colleagues and treat them in the manor that you will want to be treated for your long and hopefully illustrious career.

Within foot and ankle as a sub speciality there is overlap with various health care professions, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, osteopaths, orthotists, podiatrists, chiropodists and podiatric surgeons. It is imperative to a good overall care and your working life that you collaborate well with all of these. Within our department, we have all the aforementioned, other than chiropodists and osteopaths who work in the community. Prior to a reorganisation, we worked separately and met for a bi-monthly multidisciplinary team meeting. However, we realised that this was not the best way to work collaboratively and have a greater understanding of what the other aspects of the team were doing during their patient management.

We organised a ‘Big Foot Clinic’ where all the complex new and follow up foot and ankle patients were seen and treated by orthopaedic and podiatric surgeons alike. We therefore could give collaborative treatment plans and immediate second opinions with complex issues which benefits the NHS by reducing appointments/resources as well as the individual surgeons and patients. The diabetic and forefoot work is predominantly managed by the podiatrists and podiatric surgeons and the hindfoot and ankle work by the orthopaedic surgeons. We also started joint operating lists between podiatric and orthopaedic surgeons to allow operations like Charcot reconstructions to be done safely and with the knowledge and skill set of both parties.

I believe there is a large amount of foot and ankle pathology and it currently feels like an ever-expanding speciality. The ability to work closely with other providers and distribute work appropriately will facilitate the expanding need of the diabetic population as well as the elective and traumatic foot and ankle demand.

Annual and study leave can be very difficult to achieve when you are a sole-trader orthopaedic surgeon. This is facilitated by buddying-up with someone of the same sub speciality so that you can have someone with the appropriate skill set taking ownership of your patients in your absence.

Revalidation is facilitated by ongoing organisation and saving the appropriate evidence as it occurs in a set folder. Secretarial support is very useful in this regard.

Above all else, enjoy your day-to-day training and work, as it is a privilege to have such an opportunity and by doing so, you can easily achieve Ikigai!