"But first, block the hip": Evaluating hip fracture care using the HQO hip fracture quality standard leads to improved fascia iliac compartment block practices

By Prabjit Ajrawat

Medical Student at the University of Buckingham

Introduction

Hip fractures (HF) are injuries that require prompt orthopaedic intervention. Among elderly patients, HF significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality, with one-year mortality rates of 31% in the UK and 23% in Canada1. Due to aging demographics in industrial countries, the incidence of HF is expected to double by 20502. Consequently, HF place a substantial financial strain on healthcare systems, with annual costs exceeding £2 billion in the UK and $1.1 billion in Canada3,4.

Managing HF requires a multidisciplinary effort between various departments from the time of presentation to community discharge. However, variation in HF care exists due to organisational factors, which can partly explain differences in patient outcomes and costs5. To improve care, clinical guidelines and quality standards have emerged to reduce the variability in HF-related care. Implementing and then systematically auditing best practices can improve patient experiences and reduce healthcare system burdens. As such, an initial audit assessed adherence to the Health Quality Ontario (HQO) quality standard and identified a quality improvement project (QUIP) for a specific area for enhancement.

Comparing the HQO Standard and NICE Guidelines

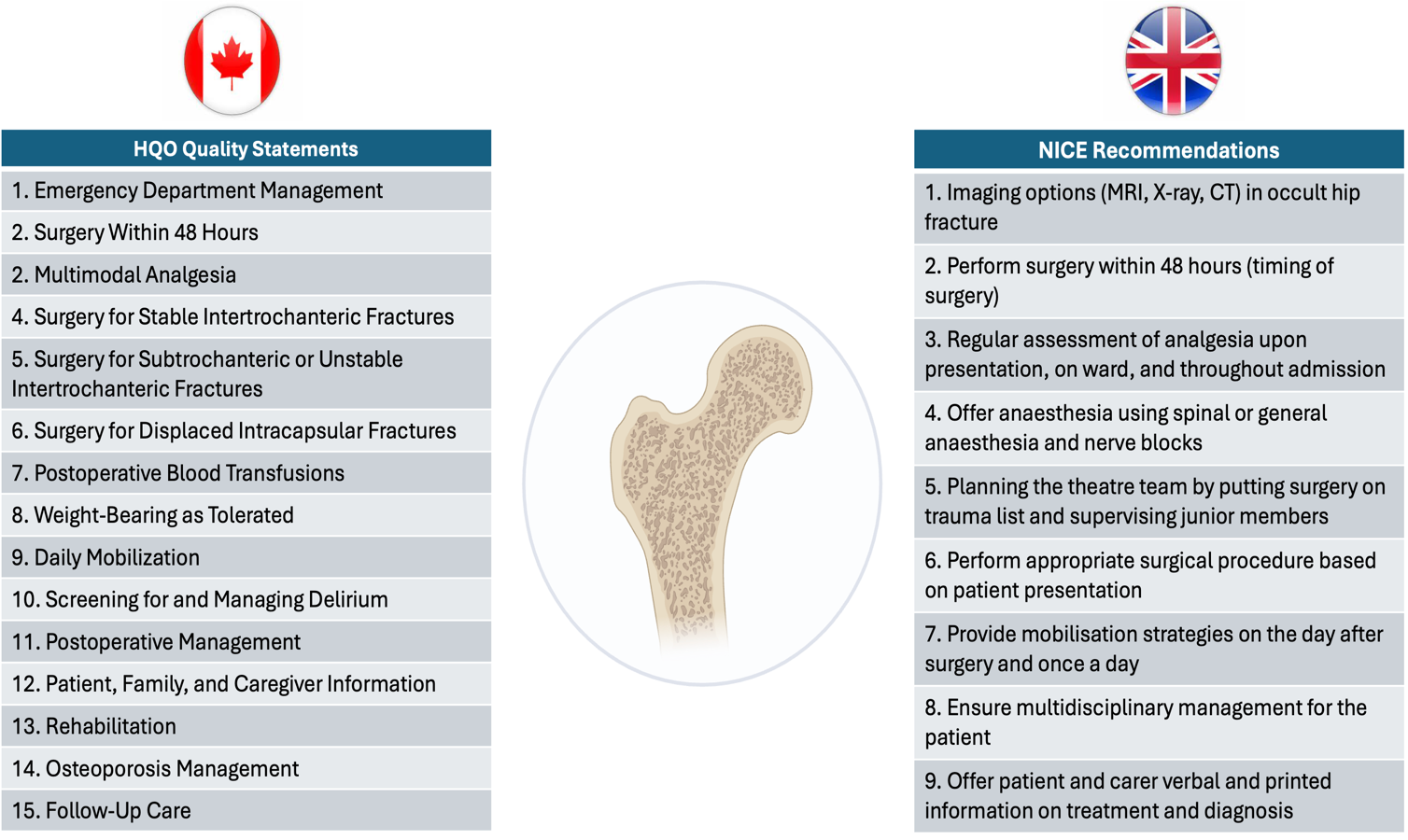

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines aim to improve UK HF care by offering nine recommendations covering various aspects such as imaging, surgical care, patient information, and multidisciplinary management6. In contrast, the Canadian HQO quality standard7 includes 15 quality statements with suggested process quality indicators for each quality statement (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Overview of the NICE Recommendations and HQO Standard.

Audit design and strategy (Plan and do)

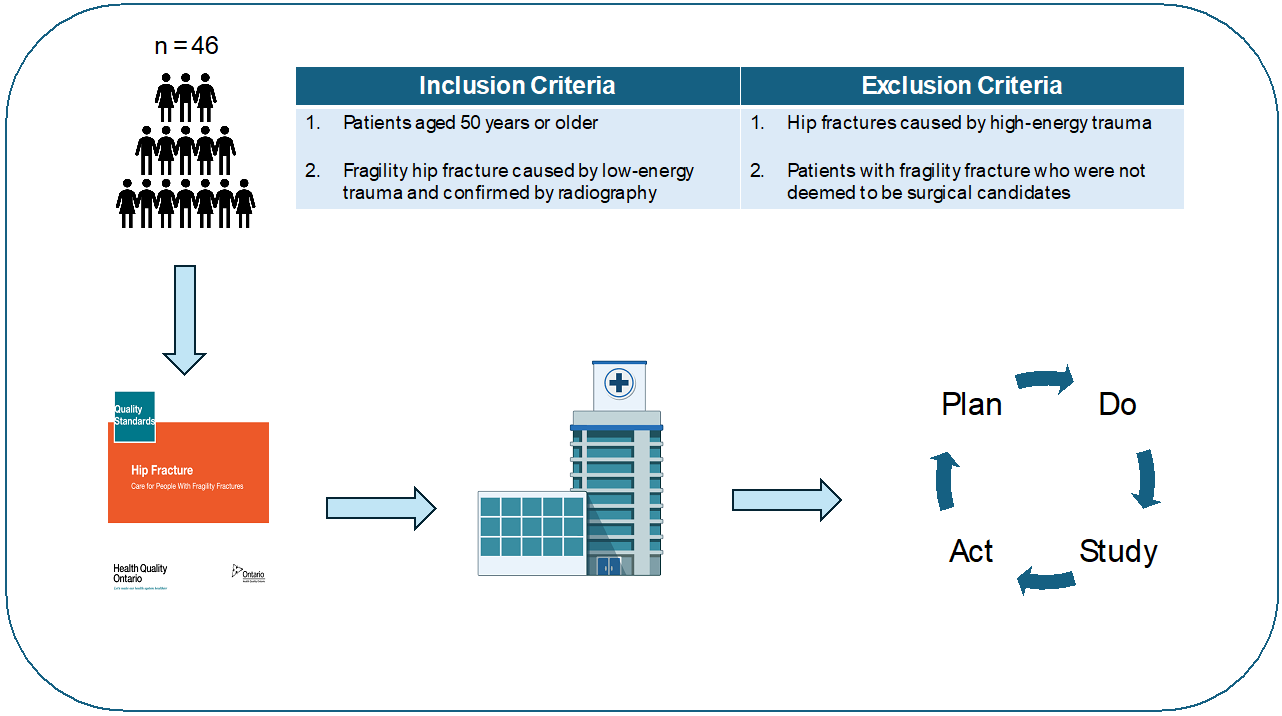

HF patients presenting at St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada were identified through electronic diagnostic codes and handover documentation. Only those aged 50 years or older with fragility-related HF were included. A total of 46 patients met the inclusion criteria (Figure 2).

From the quality statements, a total of 27 quality indicators were selected for this audit. Adherence targets were set to quantify performance and prioritise improvement areas. A rate of 90% signified excellent performance, 60% or more was considered moderate, and below 60% was deemed low. The target adherence rate for indwelling catheters was 10% or lower, as a lower rate is preferable to limit complications and infections.

Figure 2: Project outline and inclusion criteria.

Audit findings and departmental performance (Study)

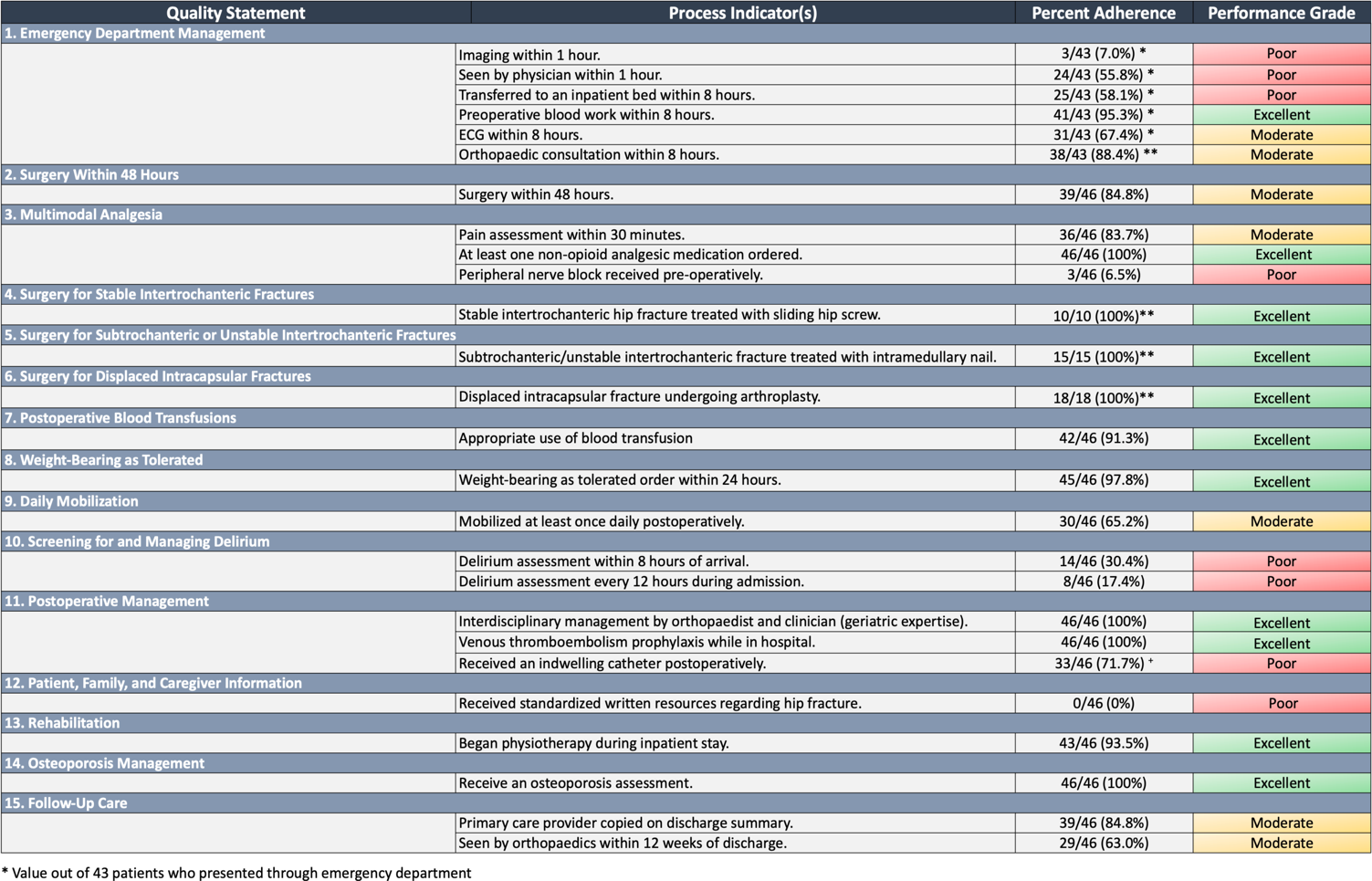

The audit revealed various aspects of hospital-wide orthopedic care performance (Table 1). Excellent performances were observed in surgical and post-operative care statements #4-8 (surgical intervention choice, blood transfusion, weight-bearing status), #13 (rehabilitation) and #14 (osteoporosis management). Excellent performance in these areas is backed by standardised processes and electronic order sets within the orthopedic department, including routine bone health assessment and appropriate osteoporosis management.

In contrast, the audit indicated poor performance for quality statements #10 (delirium) and #12 (patient information). However, strikingly poor performance was observed among the following indicators: imaging within one hour (6.9%), administrating pre-operative fascia iliac compartment blocks (FICB, 6.5%), delirium assessment within eight hours of triage (30.4%) or every 12 hours during admission (17.4%), utilising postoperative indwelling urinary catheter (71.7%), and provision of written HF resources during inpatient stay (0%). Enhancing performance in certain low-performing areas poses challenges due to the hospital's local context. For instance, evaluating HF patients within one hour in the emergency department would be challenging due to the demands of operating in a large metropolitan Level 1 trauma hospital. However, addressing poor performance areas prompted a targeted QUIP that focused on increasing FICB utilisation as this represented a significant clinical problem that was feasible to address.

Table 1: Percentage of hip fracture patients receiving recommended care.

Improving departmental fascia iliac blocks practices (Act)

Pain control is an important aspect of HF care, with the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) 'Standards for Trauma' recognising immediate analgesia as a key outcome8 and suggesting FICB when appropriate9. Utilising FICB decreases opioid consumption, improves pain management, shortens hospital stay, and may prevent delirium and infections in older patients10-13. Despite both the HQO and NICE recommending multimodal analgesia with FICB as adjuncts, adherence to this recommendation remains low10,14,15.

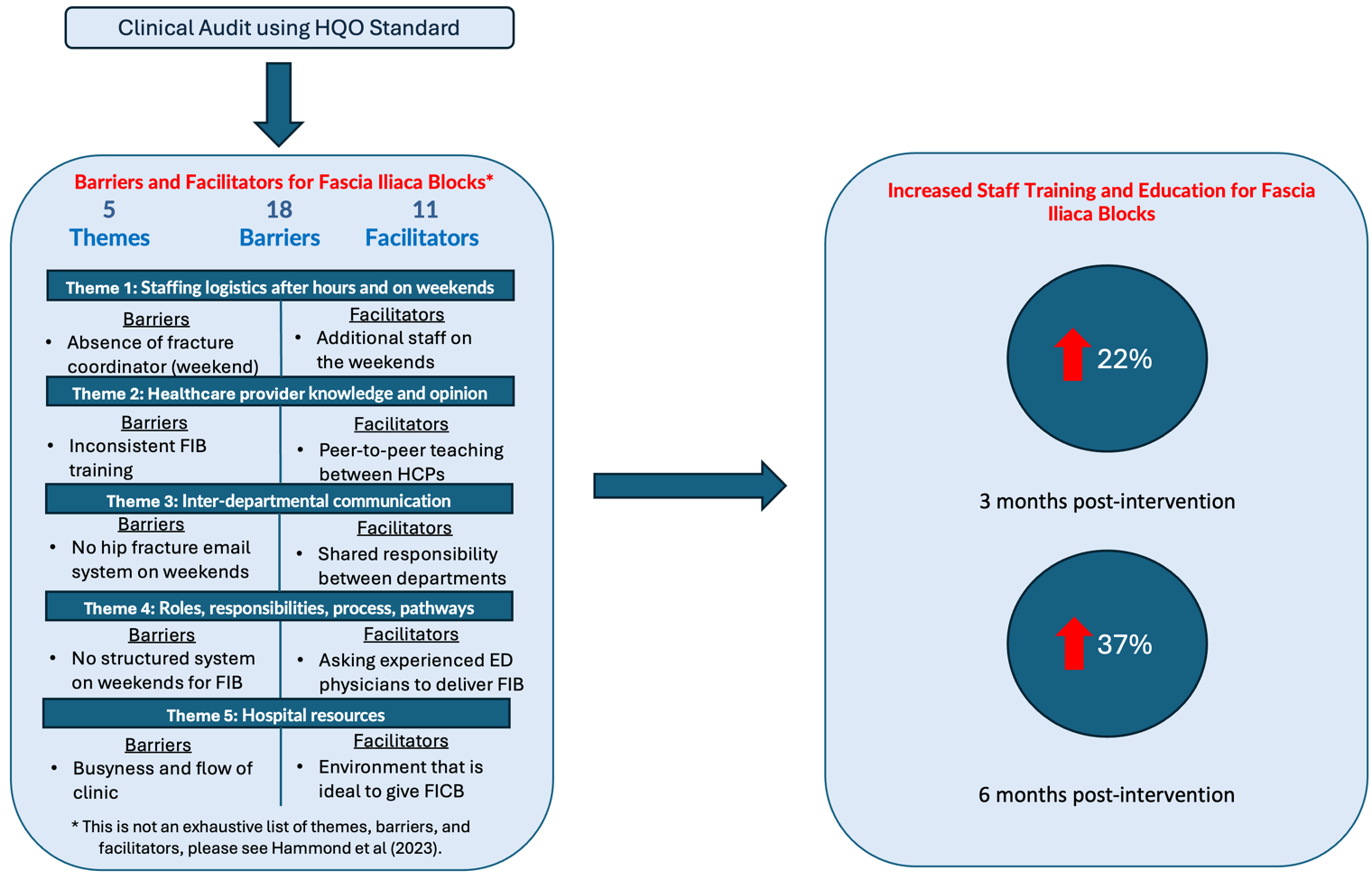

In our department, we aimed to understand the barriers behind the low uptake of FICBs. Interviewing staff and conducting site observations revealed five themes, including 18 barriers and 11 facilitators16, that explained the underutilisation of FICBs, especially during weekends and after-hours (Figure 3). For instance, the fracture liaison coordinator's absence on weekends, inconsistent training among junior doctors and staff, and the lack of assigned roles posed as significant barriers16. Potential facilitators included appointing clinical 'champions' for support, adding weekend staff and an after-hours FICBs team, restructuring the environment to facilitate interdepartmental communication, and tailoring staff educational materials and their respective roles16.

The FICB technique can be taught peer-to-peer to most healthcare providers and junior doctors17. In fact, the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland also supports FICB administration by non-physician providers18, such as nurses and paramedics19-21. Considering this and recognising the above-mentioned barriers prompted the department to enhance staff training and education. In the first phase, the department presented staff with information about the process and benefits of early FICB. In the second phase, staff received video tutorials, pocket-sized FICB procedure instructional cards, and a directory of experienced physicians available to assist with FICB procedures. Overall, identifying the barriers and facilitators, implementing additional training, and promoting multidisciplinary collaboration led to a 22% and 37% increase of FICB administration in three and six months, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Overview of the QUIP that arose from the audit.

Conclusion

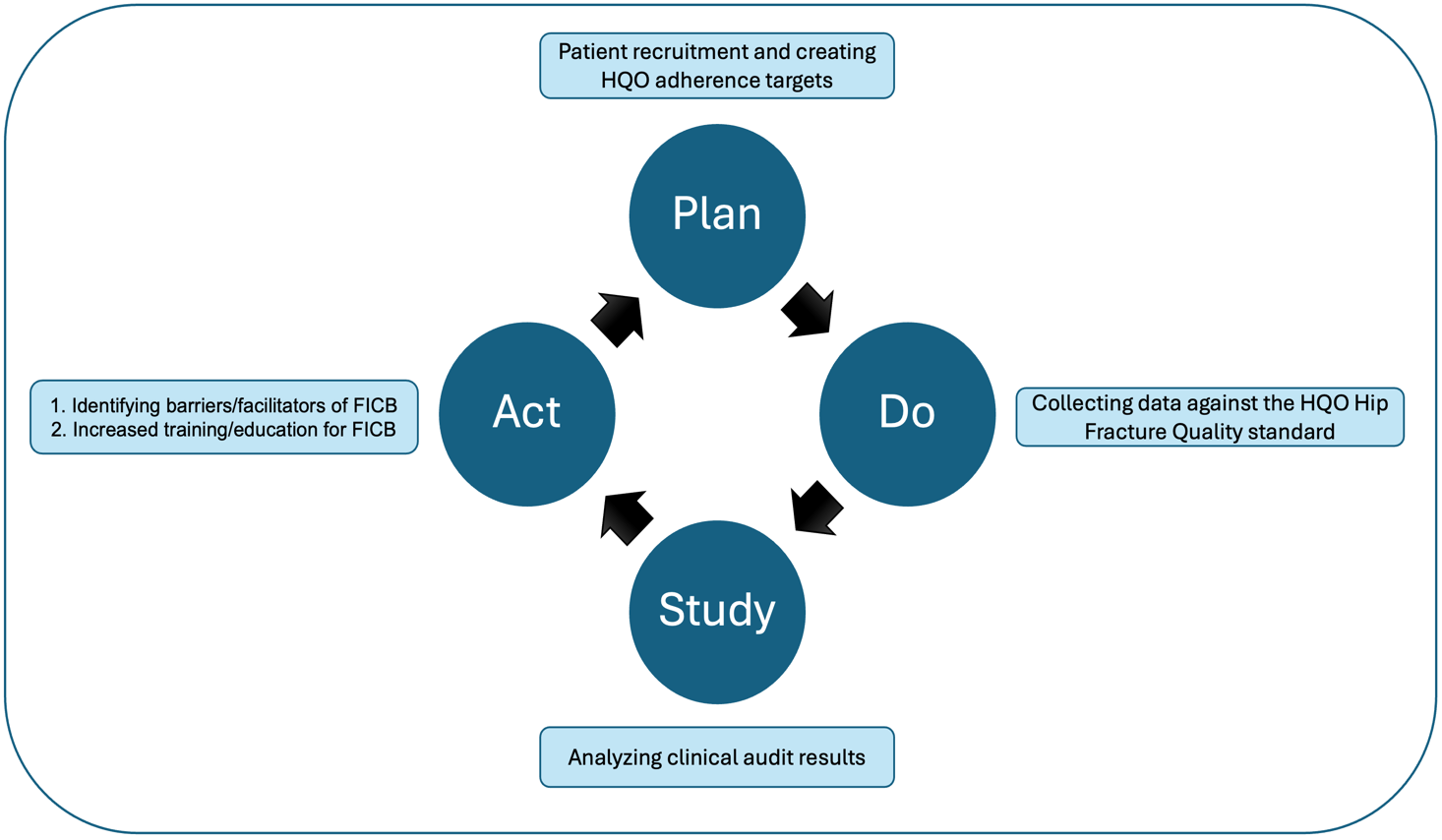

Healthcare systems excel through continuous improvement and patient safety enhancement. This QUIP highlighted the importance of evaluating departmental performance against evidence-based standards and the essential role of multidisciplinary care in optimising HF management (Figure 4). Identifying barriers and implementing staff training on FICB procedures provides insights that can guide other institutions to improve patient safety and outcomes, optimise efficiency, and improve cost-effectiveness. Continual improvements in HF care are crucial for strengthening today's healthcare system against future demographic and systemic challenges.

Figure 4: Project summary applying the PDSA cycle.

References

- Papanicolas I, Riley K, Abiona O, et al. Differences in health outcomes for high-need high-cost patients across high-income countries. Health Serv Res. 2021;56 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):1347-1357.

- Sing CW, Lin TC, Bartholomew S, et al. Global Epidemiology of Hip Fractures: Secular Trends in Incidence Rate, Post-Fracture Treatment, and All-Cause Mortality. J Bone Miner Res. 2023;38(8):1064-1075.

- Nikitovic M, Wodchis WP, Krahn MD, Cadarette SM. Direct health-care costs attributed to hip fractures among seniors: a matched cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(2):659-669.

- Burge RT, Worley D, Johansen A, Bhattacharyya S, Bose U. The cost of osteoporotic fractures in the UK: projections for 2000–2020. Journal of Medical Economics. 2001;4(1-4):51-62.

- Baji P, Patel R, Judge A, et al. Organisational factors associated with hospital costs and patient mortality in the 365 days following hip fracture in England and Wales (REDUCE): a record-linkage cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023;4(8):e386-e398.

- The National Institue for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Hip fracture: management [internet]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124. Published 2011. Accessed 2024.

- Health Quality Ontario (HQO). Quality standards for hip fracture care for people with fragility fractures [internet]. http://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/documents/evidence/quality-standards/qs-hip-fracture-clinical-guide-en.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed2024.

- British Othropaedic Association (BOA). Standards for Trauma: Patients sustaining a fragility hip fracture [internet]. https://www.boa.ac.uk/standards-guidance/boasts.html. Published 2012. Accessed 2024.

- British Othropaedic Association (BOA). The care of the older or frail orthopaedic trauma patient [internet]. https://www.boa.ac.uk/static/a30f1f4c-210e-4ee2-98fd14a8a04093fe/boast-frail-and-older-care-final.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed2024.

- Callear J, Shah K. Analgesia in hip fractures. Do fascia-iliac blocks make any difference? BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1).

- Foss NB, Kristensen BB, Bundgaard M, et al. Fascia iliaca compartment blockade for acute pain control in hip fracture patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(4):773-778.

- Morrison RS, Magaziner J, Gilbert M, et al. Relationship between pain and opioid analgesics on the development of delirium following hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):76-81.

- Hao C, Li C, Cao R, et al. Effects of Perioperative Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block on Postoperative Pain and Hip Function in Elderly Patients With Hip Fracture. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2022;13:21514593221092883.

- White SM, Griffiths R, Holloway J, Shannon A. Anaesthesia for proximal femoral fracture in the UK: first report from the NHS Hip Fracture Anaesthesia Network. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(3):243-248.

- Okereke IC, Abdelmonem M. Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block for Hip Fractures: Improving Clinical Practice by Audit. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e17836.

- Hammond M, Law V, de Launay KQ, et al. Using implementation science to promote the use of the fascia iliaca blocks in hip fracture care. Can J Anaesth. 2023.

- Hanna L, Gulati A, Graham A. The role of fascia iliaca blocks in hip fractures: a prospective case-control study and feasibility assessment of a junior-doctor-delivered service. ISRN Orthop. 2014;2014:191306.

- The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI). Fascia iliaca blocks and non-physician practitioners: AAGBI position statement [internet]. https://www.ra-uk.org/images/Documents/Fascia_Iliaca_statement_22JAN2013.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed 2024.

- Dochez E, van Geffen GJ, Bruhn J, Hoogerwerf N, van de Pas H, Scheffer G. Prehospital administered fascia iliaca compartment block by emergency medical service nurses, a feasibility study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2014;22:38.

- McRae PJ, Bendall JC, Madigan V, Middleton PM. Paramedic-performed Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block for Femoral Fractures: A Controlled Trial. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(5):581-589.

- Evans BA, Brown A, Fegan G, et al. Is fascia iliaca compartment block administered by paramedics for suspected hip fracture acceptable to patients? A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e033398.